Season Smart Food from the Terai

by Sanjib Chaudhary

What do you do if you are a fish lover and there are no fish available in the surroundings? You dry them and save them for the future during the rainy season, when the water bodies around you have plenty of fishes. And who knows how to do it better than the indigenous peoples living in the southern plains of Nepal?

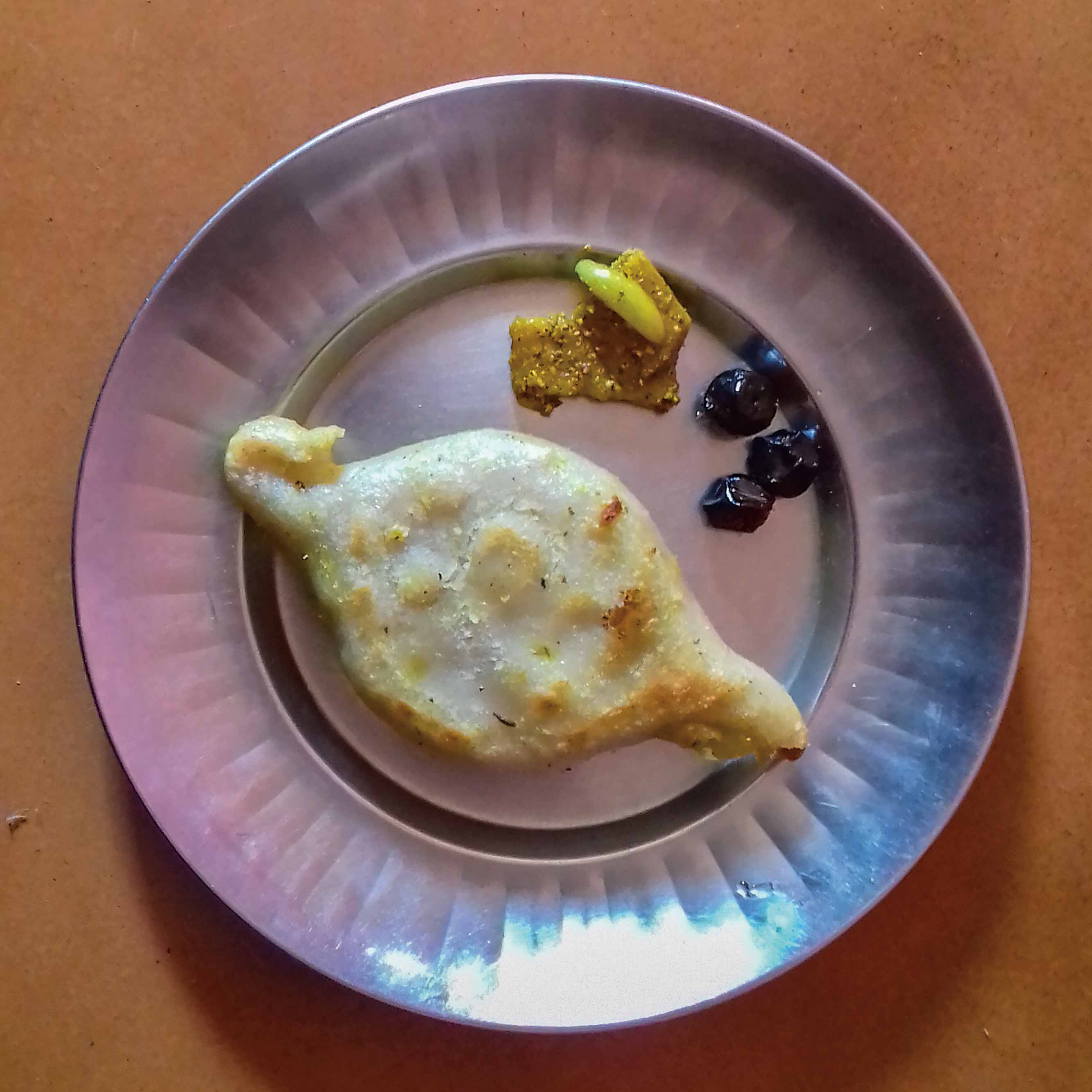

Sidhara–lip-smacking dish for fish lovers

Indigenous people like Tharus, Danuwars, Musahars, and others prepare sidhara, a dried cake of dried fishes, taro stem, and turmeric, so that they can enjoy the taste of fish throughout the year. Radish, green chillies, and garlic are added to the cake to enhance the taste. The aroma is pungent, the taste is bitter, and still it is one of the delicacies eaten by the people in the southern plains!

During the rainy season, when the fields are awash with rainwater and there is no dearth of water, there are fish everywhere—of all sizes and tastes. The people who live in the area eat the fish fresh and dry the surplus ones to make sukuthi, dried fish to be used during the winter and other seasons when fish aren’t found in plenty. The dried fish and dried vegetables are saved for times when it is difficult to get fresh fish and vegetables.

The dedhna and ponthi varieties are preferred to prepare sidhara. Both the varieties are found in abundance in the paddy fields and public water sources. The dedhnas are one of the smallest varieties of edible fishes and can be eaten with its tender bones. They vary in size between half-an-inch to one-and-half inch in length (so, the name dedhna, meaning one-and- half). The second variety, ponthi, is a little bit bigger and wider than the dedhna, and it too can be eaten with its bones.

Taro, or Colocasia, is found in abundance in the swampy places and ditches, and nowadays even cultivated in kitchen gardens. The leaves are eaten separately, and the stems are used either for the sidhara or dried after being cut into small pieces. The dried taro is eaten in the winter and rainy seasons, when there is dearth of fresh vegetables.

The dried fishes, together with the taro stem and turmeric powder, is ground and made into small cakes. The cakes are left to dry in the sun for 10-15 days, and after that it is stored in a dry place for future use. Whenever needed, the cakes are crushed and broken into tiny crumbs and fried on mustard oil, together with pieces of onion, green chilies, radish, and spices. Then, water and salt are added to it, and then garnished with green coriander leaves. It can be served with puffed or beaten rice.

Dried fish is very rich source of protein, containing 80-85% protein. Researches have shown that some compounds in turmeric have anti-fungal and anti-bacterial properties. Besides being used as a coloring agent in key dishes, it enhances the taste and has medicinal properties, as well. Taro is eaten widely in the Indian subcontinent. The extra additions— green chilies, radish, and garlic enhance the taste, reduce the odor, and are good for health.

Biriya–the delicious dry greens

And if you’re a vegetarian, there’s something special for you, too.

During the winter, women collect green vegetables, especially mustard leaves, broad leaf mustard, and grass peas, let them wither a bit, and wrap them in black gram paste. Drying them in the sun makes biriya, as they call it locally. It is stored to be cooked during the rainy season, when green vegetables are scarce. The black gram paste gives a tangy taste to biriya, and also works as a preservative. Plus, it's a source of high protein.

It’s easy to cook biriya. The wrapped vegetables are fried in mustard, oil along with onion and chilies. Then, spices, turmeric powder, salt, and water are added and cooked on low heat. Biriya can be cooked together with potato, as well.

Next time you visit the Terai, ask for the sidhara and biriya. I am sure your taste buds will be delighted to savor the traditional food!