How do you inspire the masses? Show them movies in their own communities.

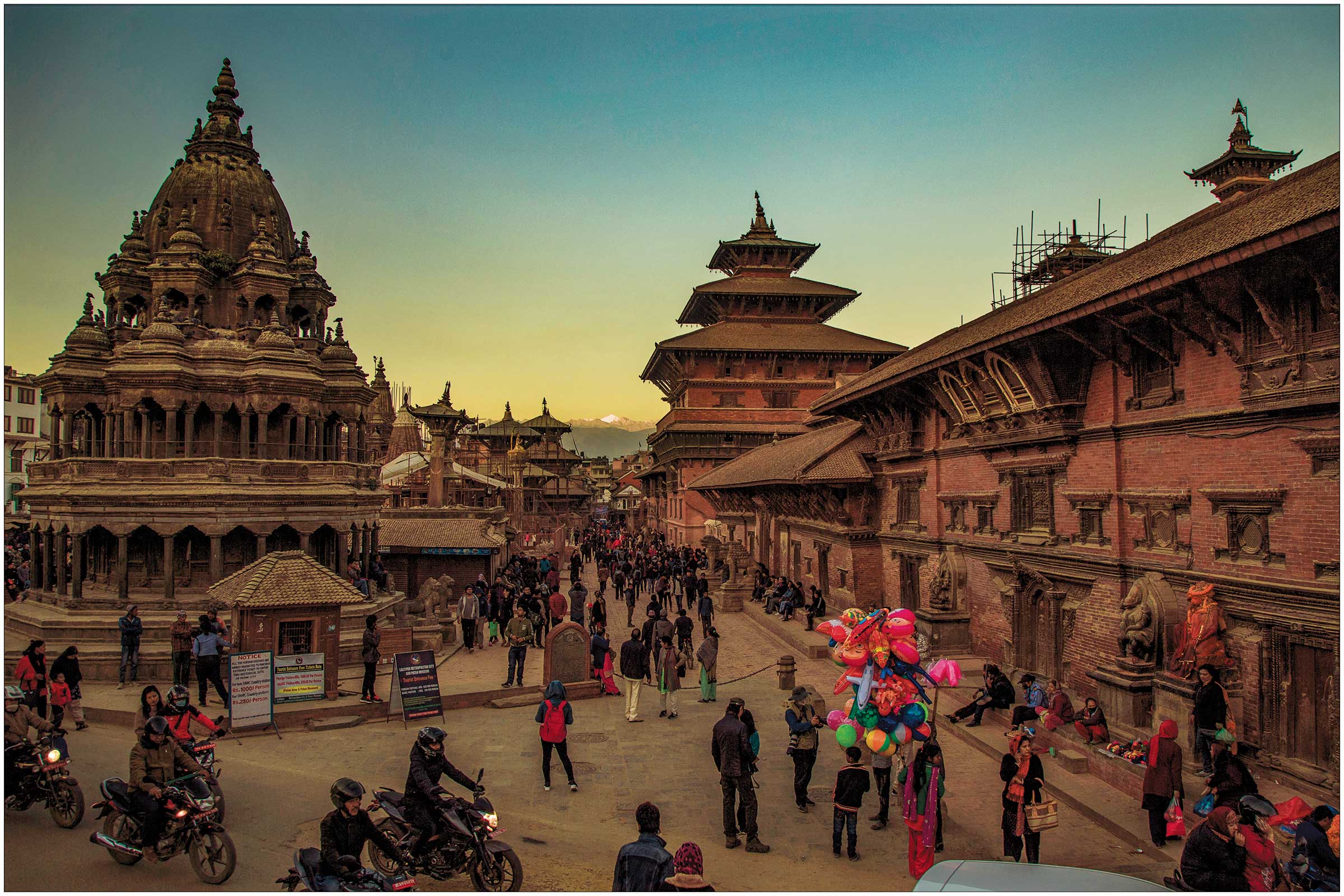

When we took the Makhan Galli, a long time ago, my father told me that this was where they used to screen movies. “They didn’t allow it during the Panchayati regime”, he’d told me excitedly, “so, they’d show them in this galli.” That could have been one of the very first public screenings of movies in Kathmandu. A culture which quickly faded, however, with the advent of commercial theaters.

Not that the public spaces in Kathmandu are particularly friendly for screening either. The dabus are designed to host dances and plays, which are regular features of jatras since ancient times. But for the last couple of years, Bato Ko Cinema, a project by Sattya Media Art Collectives, has been taking documentaries to the streets of Kathmandu. During the month of November and December this year, the project collaborated with Movies that Matter and screened six documentaries on the theme of Dignity of Labour, at seven places in Kathmandu Valley, Banepa and Birgunj.

During the first screening that took place in Maruhiti of Kathmandu, there were local people of different ages, sitting around the hiti to watch the documentary, The Desert Eats Us, made by popular Nepali filmmaker Kesang Tseten. There were people – men and women alike – who’d come to fetch water, lingering with their eyes glued to the screen. I could see that the movie was doing its work – it was affecting the audience. I followed one elderly woman sitting in a corner of the hiti. She told me that the movie made her realize how difficult it was for most of her relatives and fellow villagers who had migrated to the Middle East. A majority of the audience reflected the same sentiment. Most also, voiced that they would try and dissuade anybody they knew who were going to try their luck as migrant laborers.

Same was the case in Kirtipur, Mangalbazaar and even Banepa. During the second day of second screening at Mangalbazaar, where they screened five other shorter movies, Surendra Nakarmi, who’d returned back from Qatar as a migrant worker, took the platform to share his story. Pete Pattisson, a video and photo journalist based in Kathmandu whose movie Qatar’s World Cup Slaves was screened during the event, was also present to share what he’d seen.

The various screenings had a singular objective— to create a platform where people could share their views, get inspired and become aware of the trappings and pitfalls of migration. And I can say that this was successfully done through those movies. While my father would have left Makhan Galli feeling relaxed after a Bollywood flick, I left the screenings in silence.