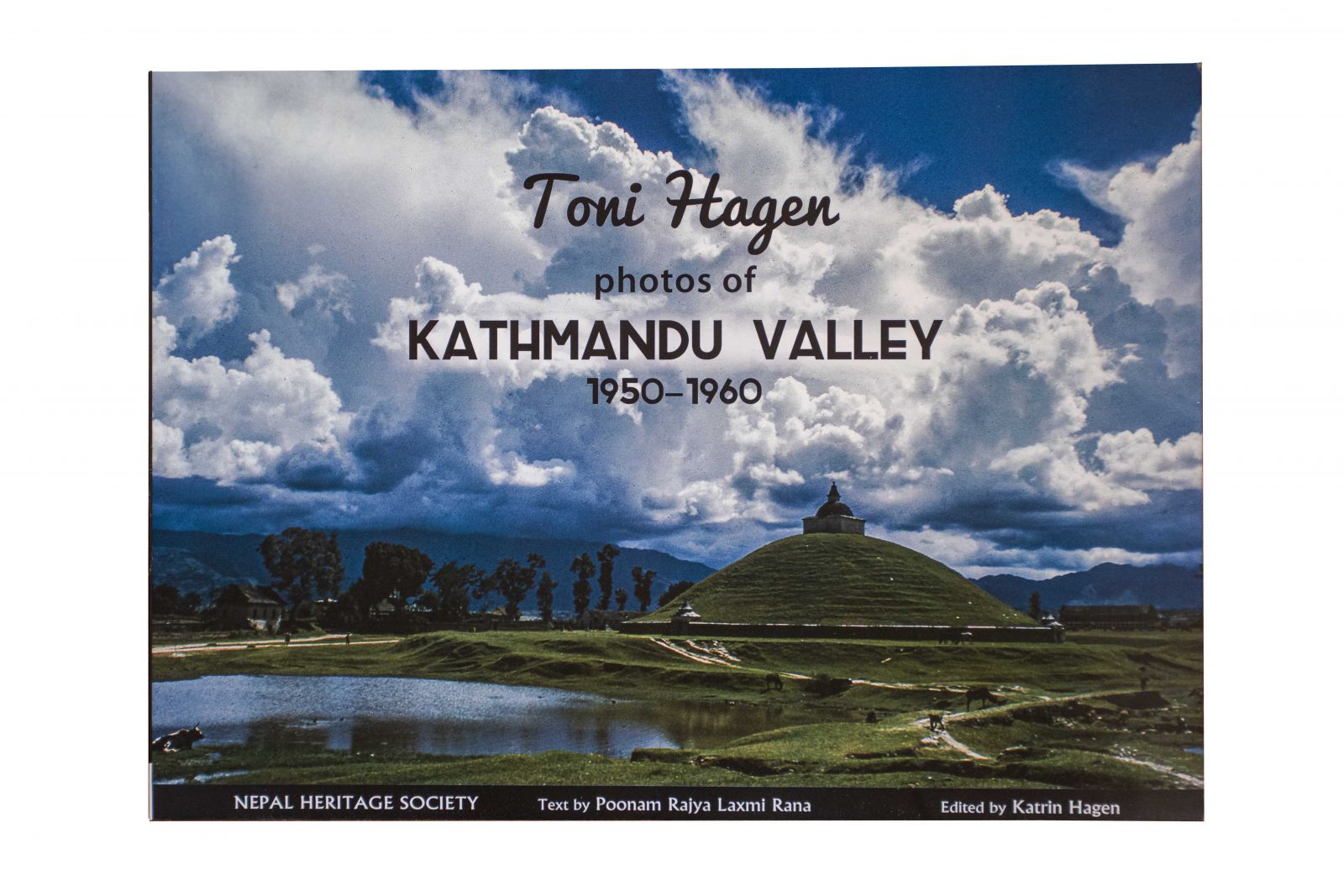

This important collection of photographs evokes a forgotten era when the Kathmandu Valley was rural, verdant, and astonishingly empty of people. White peaks loom pristine in the unpolluted air, the unpaved roads are empty of vehicles and terraced fields are uncluttered with urban sprawl.

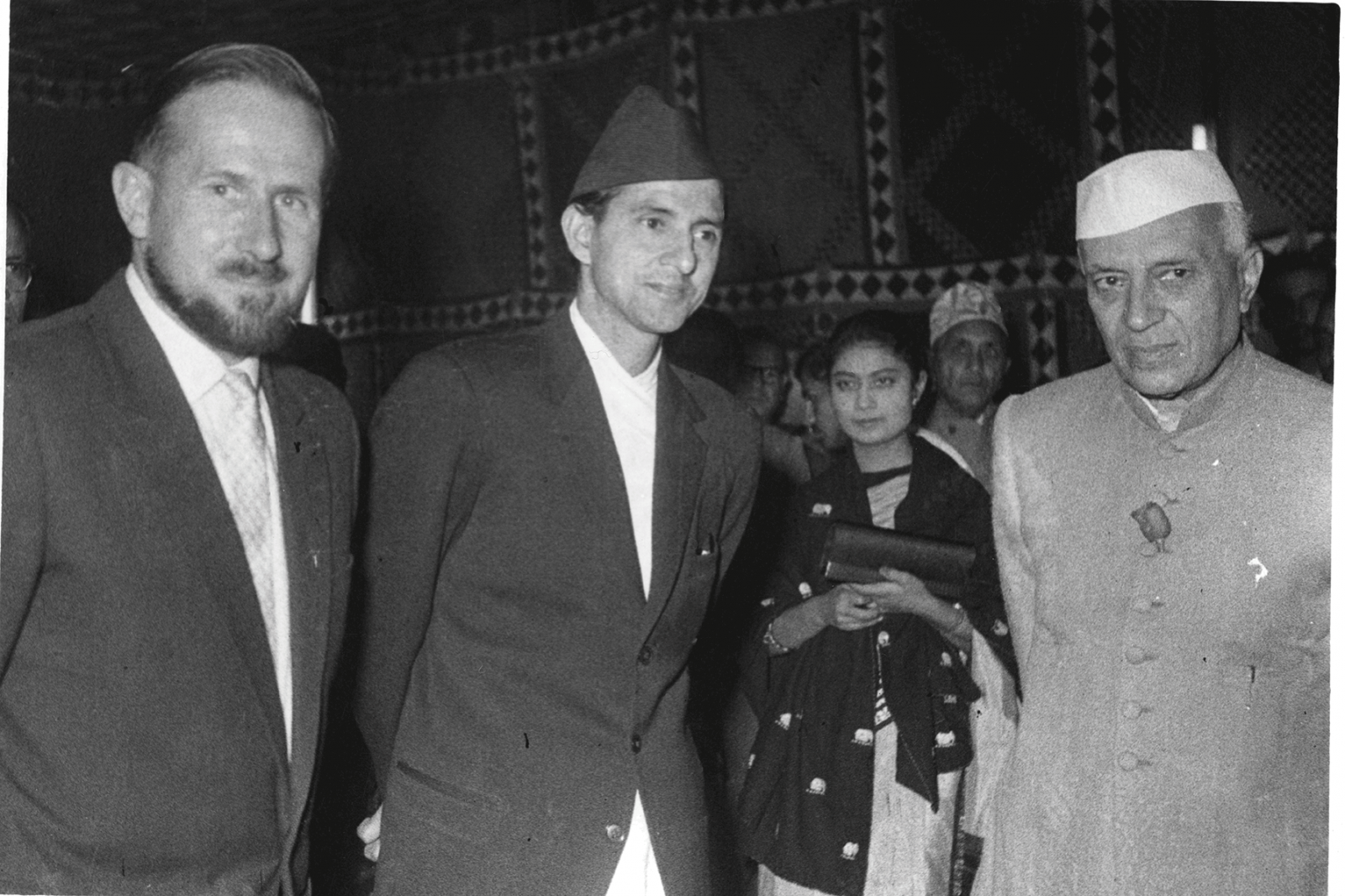

These early images are the exemplary work of the fabled Swiss development guru, Toni Hagen (1917-2003), a serious man who single-handedly explored and surveyed Nepal when he first arrived in 1950. The country had, till then, been isolated during the reclusive Rana regime, and he was one of the first foreigners to penetrate the forbidden kingdom and its most remote corners.

Edited by Toni’s dedicated daughter, Dr Katrin Hagen, with text by Professor Poonam Rajya Laxmi Rana, these previously unseen photographs are published by the Nepal Heritage Society, with the untiring commitment and support of NHS President and the Hagens’ long-time family friend, Mrs Ambica Shrestha.

Edited by Toni’s dedicated daughter, Dr Katrin Hagen, with text by Professor Poonam Rajya Laxmi Rana, these previously unseen photographs are published by the Nepal Heritage Society, with the untiring commitment and support of NHS President and the Hagens’ long-time family friend, Mrs Ambica Shrestha.

Dreaming of the Himalaya during his childhood amidst the Alps, Toni Hagen qualified as a geologist, initially attempting to apply Swiss scientific logic to Nepal. He began with air surveys but soon resorted to foot, reputedly walking 14,000 miles across the entire country during the 1950s. He was the first person to reveal and record Nepal’s complex topography, geography and social fabric for his United Nations employers and His Majesty’s Government. Toni Hagen’s books, films and photos are classics, the received wisdom from a uniquely experienced perspective.

In this album, his emerald valley images remind us of the time when only a kora of thatched houses separated the great stupa of Bauddha from agricultural fields and rice terraces. Goats and sheep graze the Gauchar airfield, guinea fowl are reared on Tundikhel, and bulls rest in Basantapur square amidst government officials trying to stay warm in the winter sun.

But in these haunting pictures many of the sparse population, going about their business in familiar Valley landmarks, are barefoot and scantily clad, with poverty etched into careworn faces. Despite a population of only 300,000 inhabitants in the bucolic calm and open spaces of 1950s’ Kathmandu Valley, the surrounding hills are denuded of trees and lacking in forest cover compared to the same views today.

Realising that Nepal urgently required humanitarian assistance, Toni Hagen abandoned geology and dedicated his efforts to development work. The health, education and livelihood of the people were what mattered most, so he addressed the grassroots by asking villagers what they most wanted and needed. It was Toni Hagen who secured Nepal’s first development assistance, from the government of Switzerland, and he who laid the foundations of Nepal’s carpet industry to create employment for refugees.

Wary of unplanned roads and large-scale hydro installations, Toni worried about Nepal’s headlong rush into modernisation, preferring a more measured approach. Rooted in Swiss federalism, he was ahead of his time in advocating that Nepal’s governance would benefit from democracy and decentralisation.

By the time I knew Toni he was older and slower, but still smiling and serious, with an undiminished passion for progress and an infectious faith in the youth of Nepal. I enjoyed his solid Swiss outlook and his perceptive Nepal insights, delivered in a rich lilting accent with grave, kind eyes.

This new book is a worthy addition to Tony Hagen’s significant contribution to Nepal. Featuring extraordinary full-colour spreads of the Kathmandu Valley that he loved, it enhances our understanding of mid 20th century life and captures the atmosphere of that bygone decade during which Nepal first opened to foreign visitors.

Liquid Gold: Nepal's Beer Industry Is Growing And Changing Fast

One need only glance at the beer section of the local liquor store to see that...