I spent most of my early years in the northern half of the Kathmandu Valley. Much of this was within the brick walls of Budhanilkantha School, which sprawls at the base of Shivapuri, as well as Maharajgunj and Dhapasi. My experience of living in the metropolis was conditioned accordingly, and complicated by time outside the country. When I did return to Nepal ‘for good’, it was on semi-nomadic terms: I moved out of home, and across the river.

For one accustomed to the northern slopes of the Valley, moving to Lalitpur was very much like entering a distinct city, albeit one conjoined to Kathmandu by the Bagmati. For one, I was reminded that despite everything you could still see the Himalaya on a clear day from Lalitpur, Ganesh to Gaurishankar, simply because it was far away enough from the Shivapuri massif. Familiarity with the southern sister of Kathmandu had been limited to courtesy visits to relatives in Pulchowk, and an internship off the main road at Kupondole, close enough to Kathmandu as to seem part of it. I was never curious enough to actually venture into the heart of the old city—Patan—until I visited a friend who was building a house just south of the famed temple of Bagalamukhi.

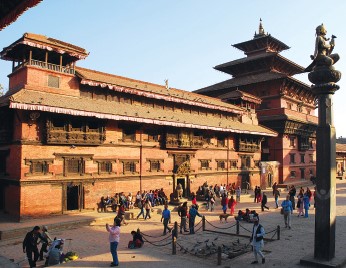

Coming up the hill to Pulchowk, I got off at the once-futuristic, now dowdy Lalitpur sub-metropolitan building, its empty fountains swirling with dead leaves, and turned left towards Mangal Bazaar. I had no idea where I was going beyond a vague idea that Patan Durbar Square (which I only remembered as an assortment of temples in a vacuum) was somewhere ahead of me. The narrow streets recalled Asan, but the neighborhoods I was passing through were more sedate. “The board says Dhaugal,” I informed my friend via phone. “Oh, now it’s…Kwalakhu?” This was no medieval, consciously preserved Bhaktapur, but more of the past had been retained than in Kathmandu, even amidst the busy shutter shops. When I finally stumbled into the courtyard before my friend’s house, I saw how she had preserved her own past by planning her future in the space her own mother was born into, long after the original structure had collapsed. I moved into Mangal Bazaar a couple of years later.

Coming up the hill to Pulchowk, I got off at the once-futuristic, now dowdy Lalitpur sub-metropolitan building, its empty fountains swirling with dead leaves, and turned left towards Mangal Bazaar. I had no idea where I was going beyond a vague idea that Patan Durbar Square (which I only remembered as an assortment of temples in a vacuum) was somewhere ahead of me. The narrow streets recalled Asan, but the neighborhoods I was passing through were more sedate. “The board says Dhaugal,” I informed my friend via phone. “Oh, now it’s…Kwalakhu?” This was no medieval, consciously preserved Bhaktapur, but more of the past had been retained than in Kathmandu, even amidst the busy shutter shops. When I finally stumbled into the courtyard before my friend’s house, I saw how she had preserved her own past by planning her future in the space her own mother was born into, long after the original structure had collapsed. I moved into Mangal Bazaar a couple of years later.

Living in Lalitpur this past decade—Mangal Bazaar, Sanepa, Bakhundole, Balkumari, Bagdole and back to Balkumari (with a quick Kathmandu detour in Chundevi)—has really opened my eyes (and ears) to the extraordinary place that is the Kathmandu Valley. To be living in a rented flat an hour away from home in the denatured suburbs of Dhapasi, through a courtyard that led to another courtyard, was novelty enough. It also brought me into direct contact with a whole flotilla of service providers I had been insulated from by my parent’s clockwork household—the gas guy, the water guy, utility offices, vegetable markets, kirana pasal, itinerant vendors of the material and the spiritual, and the curious sub-species of the landlord.

The market quarter of Mangal Bazaar is a world unto itself, and as a Nepali speaker, I was merely embedded in a Newar planet. Mostly, I would have no idea what festival was banging its way along the labyrinthine streets four floors below me, and I’d track their progress by ear. In the quieter moments I could hear my Shakya landlord tapping away as he worked with silver, the large caged myna calling out from across the way, and an assortment of roof dogs reaching out to the world they could sense but not see. Highlights were the Kartik Naach in Patan Durbar Square—thousands of locals crowding the mandap to witness the demon Hiranyakashipu swoon at the touch of the divine man-lion Narasimha—and the extended stay of the collapsed Rato Macchendranath chariot in front of the gate leading to my rooms. The vitality of the ‘Newarren’ of Mangal Bazaar sparked the Kathmandu Valley civilization into life for me like Kathmandu itself had never been able to.

Not counting the first plunge in 2009, I moved half a dozen times in as many years. The moving was a drag, in a literal, physical sense rather than because of any special attachment to the neighborhoods I patronized. Each time I vowed never to do it again. Yet every year a compelling reason presented itself, and I (later we) ended by packing up, loading, unloading and stacking multiplying Hydras of furniture new and old, not to mention hundreds of books, cases of clothes, and sackfuls of crockery. If ever there was an argument for the de-clutterer Marie Kondo to visit Nepal, this was it.

So I moved from an airy, charming and dysfunctional suite

of rooftop rooms (even described in a group profile of young writers in Republica as ‘minimalist’) to a cave-like but more conventional ground-floor flat in Sanepa. The change was drastic. That was Patan; this was Lalitpur, and not some fancy-pants expat loft, either. There had been a surfeit of culture; now there was none. Still, my job at the Nepali Times meant that I spent most of my days in another part of Lalitpur altogether. Barring the eponymous Kirat pilgrimage site at Sano Hattiban, a long downhill whizz on my cycle from Satdobato, my office was so far removed from the buzz of the city that even the residential tranquility of Sanepa was exciting. After all, we’d just dubbed the new strip of restro-bars along the Damkal Road ‘Jhamel’, and Patan was only a hop and a skip away.

Life happened, and I moved into my girlfriend’s flat in Bakhundol soon after. This was not much of a tonal change, being only a ten-minute stroll down the hill. ‘Lee-bheeng together’, as the Nepali press put it in articles that sounded by turn envious and condemnatory, wasn’t the easiest in Bhupi’s land of rumors, but we were living it up. I published my first book in the spring of 2011, and felt that as a bonafide writer, I should quit my job. Soon, I was helping friends organize the Kathmandu Literary Jatra (held at the Patan Museum and culminating with the crescendo of that year’s 6.9 M earthquake), and the following year, we founded the literary magazine La.Lit. These were heady times, and with more of our friends moving out of parental nests to flats in and around Patan, there was not only much to celebrate, but a surfeit of places to do it in, not least the Quixote’s Cove Bookshop in front of New Orleans. Long after the business folded and this compact old brick structure was demolished, I discovered that it had been the site for meetings of the revolutionary Praja Parishad to overthrow the Rana regime. Add the post-2015 disappearance of the old Juddha Barun Yantra (ironically, built by the Ranas to serve citizens) across the road and the vintage fire engines on display, and we have a reminder of how history can consist of more than religio-cultural heritage sites, and how easily it can be erased.

Society was changing, too. Our Bakhundol flat was sandwiched by two layers of evangelical Christians of south-east Asian extraction, whose ministrations attracted a steady stream of youth keen to wail to the accompaniment of bongos and bad guitar. For a stay-at-home writer with little sympathy for organized religion this was aggravating. I also had an ongoing turf war with the dog next door, and our crossroads location was such that every yodeling vendor who passed by did so thrice. When the opportunity arose to move to a friend’s flat in Chundevi, we bolted. Dogs still barked in Kathmandu, of course, but there were no evangelists.

Not long after moving out of Lalitpur, however, we were considering moving right back. This time, the incentive—to occupy the empty and fully furnished flat that my (now) mother-in-law had purchased—was largely economic. The downside was the flat was on the upside of things: on the sixth floor of a twelve-story tower, one of four that advertised the Westar Lifestyle in the old neighborhood of Balkumari, a short walk from Patan’s southern Bhol Dhoka. But as someone who had turned his nose up at the same, expensive middle-class fare laid out by Jhamel and wholeheartedly embraced the salt-of-the-earth buff buffets of Chyasal’s bhattis, this sounded rather agreeable, and never mind the earthquakes. We packed a Go Bag and moved in.

The flat was spacious, well-appointed, and most of all, new. No vermin or prehistoric grime challenged us, and there was room for my furniture, my wife’s furniture, and her mother’s. Electricity and water ran twenty-four hours. (Except for those crucial times I staggered back from a night out and realized that with the generator off I’d have to work my way up six flights of stairs.) Yes, the Ringroad was a dustbowl, but up in the air we felt removed from it all. We even had a view of the Himalaya. This was Westar Living.

When the earthquake hit, my wife was in the lift; her mother and I were down in basement parking, under heaven knows how many thousand tons of concrete. After four-score years, the Apocalypse had arrived. But we survived, like everyone we knew. The flats didn’t do so well—from top to bottom, the towers were scored with gigantic X-cracks, as if Mother Nature meant to say: You can’t live in the sky where the earth moves. And so 40-odd families fled, convening for acrimonious meetings with the developers that often descended into shouting matches. We moved back to Dhapasi.

Soon, we were circling Patan once more. Thinking it impossible to pay the ludicrous rent being charged in the nicer, whiter parts of Sanepa, we conceded we’d have to accept living with a landlord again. So, Bagdole it was, just off the Ringroad, ten minutes’ walk from Ekantakuna. This time, we had a gorgeous view of verdant Chobhar, boxy Kirtipur, and the dark hills beyond. We also had access to the closest thing we could get to a park, a trail around three massive sunken fields and marshes that had once been intended for a German sewage project, and now perfect for running (me), football (youth), driving (the upwardly mobile), morning walks (oldies), grazing (buffalos, cows, and goats), and naturing (kingfishers, drongos, kites and mongooses). Our lovely landlords had a large terraced kitchen garden, where we could pick muntala, broccoli, tomatoes, beans and squash, and a happy tendency to visit their kids in America for months at a time. You could say it was a different way of looking at Lalitpur, an acknowledgement that the city-state of Patan was once a kingdom of urban farmers. The core had expanded beyond recognition, trampling the precious loam to make way for modern living, but the gardens remained.

When we evacuated the Balkumari flat it was, in my mind, never to return. It had been folly to occupy it in the first place. But a year and a half later, upon being informed that it was ready to go, we thought, why not? It was unlikely, we convinced ourselves, that another big earthquake would hit the Valley in our lifetimes. And if it did, we could just as well be walking down any one of the strut-tamped alleys in the old city, and what then? As a Nepali, I recognized the fatalism that Dor Bahadur Bista had so precisely identified. My wife, not having grown up in Nepal, not so much. She still woke wide-eyed if I so much as coughed in bed.

But work took her back to London, and I stayed. I may have written a book on Kathmandu’s Thamel since, but I’m still far more likely to seek out long nights on the south side of the river, admiring the silhouettes of the moonlit temples as I cycle home. I’m not ready to leave. I grew up in Kathmandu, but Patan was where I discovered Nepali life outside of the round bound of family, and in circling the city and crossing it through and through I have found that you can live a life as full as anywhere in the world here, where the medieval theater state rumbles on alongside a new flowering of writers, musicians, and artists, where nature grows in the cracks of the modern metropolis and reminds us, every so often, that we are nothing, where on a clear winter’s day, you can trace a line of icy water from Langtang to Shivapuri to Chobhar, and know your place in this world.

Rabi Thapa is a writer and editor based in Nepal and the UK. He is the author of Thamel, Dark Star of Kathmandu and Nothing to Declare, and the Editor of the literary magazine La.Lit. Visit rabi-thapa.com for more.