The Shey Gompa Festival still retains its timeless mystique as it enters the 21st century.

For the last week people streamed out of the barren mountains in increasing numbers, converging onto the main trail like migrating salmon being called back by some unknown force. Some came from as far away as Mustang, others from distant villages and regions that I have never heard of. As I neared the maroon monastery, the pungent smell of burning juniper engulfed me. Rounding a massive chorten, I stopped amidst the steady flow of circumambulators and fixated on the multi-colored prayer flags trembling against the turquoise sky. The faint whuff of helicopter blades thudded through the valley, steadily growing louder. Suddenly the aircraft shot out from between the mountains and banked in a tight circle, easing down near the swollen stream below. Throngs of people rushed across the rickety wooden bridge to greet the head Lama, Rabjam Rinpoche, the guest of honor. Horns bellowed, incense piles were fanned and drums sounded to signal his arrival. Flanked on either side by monks donning crescent yellow hats and trumpets with parasol in tow, the beaming rotund figure and his procession slowly advanced up the slope in a dazzling spectacle of color and sound to help kick off the twelve-year SheyGompa festival.

SheyGompa: the name conjures up images of a remote Shangri-La filled with snow leopards, mythical mountains and saffron-robed lamas. Magic permeates the air. Enticing tales such as The Snow Leopard and Caravan only disseminate its mystique. The festival, which is celebrated every twelve years, dates back well over a thousand years when Duptop Singe Hisye, a Buddhist ascetic, battled demons that were wreaking havoc on the human race. Nearby, on holy Crystal Mountain, he destroyed the troublesome demons, initiating the festival that is still celebrated today.

SheyGompa: the name conjures up images of a remote Shangri-La filled with snow leopards, mythical mountains and saffron-robed lamas. Magic permeates the air. Enticing tales such as The Snow Leopard and Caravan only disseminate its mystique. The festival, which is celebrated every twelve years, dates back well over a thousand years when Duptop Singe Hisye, a Buddhist ascetic, battled demons that were wreaking havoc on the human race. Nearby, on holy Crystal Mountain, he destroyed the troublesome demons, initiating the festival that is still celebrated today.

This land of Dol-Pa, literally “people of the west,” seemed frozen in time, but a closer look revealed that bits and pieces of the 21st century have seeped up through the passes. Decked out in turquoise and coral jewelry and silver headdresses, women tittered to one another as high-powered lenses of photographers fired incessantly in their direction. Less shy, some men even reveled in the attention with their thick fur hats and heavily lined sheepskin jackets, or chubas. And the runny-nosed children couldn’t get enough, posing and nudging each other forward into the lenses’ eyes as they giggled and shrieked. A few photographers were so immersed in getting the ideal shot that they seemed to forget that these were actual people, not objects on display in some carnival sideshow.

The Nepali language is not the native tongue in Dolpa and is a relatively new addition to this secluded region. Nepal is a country where rugged geography and isolation have created numerous distinct ethnic groups, each with their own unique customs, rituals and languages. Most linguists agree that there are over one hundred languages spoken within its borders.

Although there were only a few specks of white in the crowd, differences were immediately apparent even amongst Nepalis. Most had Tibetan features and dress, but blended in with them were the porters, politicians, policemen and guides from Kathmandu and other far-off places. Often when I asked “Nepali bhasa aunchha?,” many just shook their heads and grinned. At times we gestured and mimed to one another to communicate, filling in gaps with smiles and laughter.

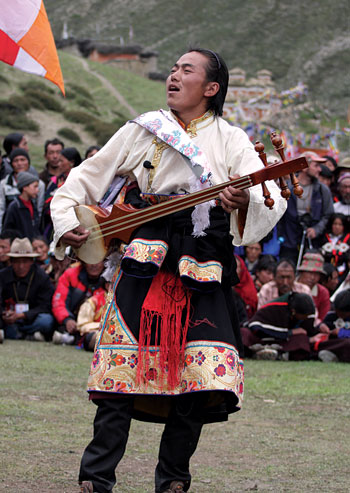

Vibrant costumes flashed and undulated to pulsating drums and clashing cymbals. Dancers appeared to be in trance-like states, their faces shadowed by grotesque demonic masks and ornate hats adorned with tiny skulls as they whirled and dipped in unison. Cham is a ritual dance that depicts the life events of Padmasambhava, or Guru Rinpoche, one of the holiest figures of Buddhism and the first transmitter of Vajrayana teachings to these lands. Unfortunately the sub-par sound system constantly distorted and cut out, not doing justice to the beautiful Tibetan dance and instruments. The rusty generator rumbling off to the side also drowned out the more timorous singers and musicians as they performed ancient renditions. At times I wished these pesky bits of technology had somehow mysteriously fallen into Phoksundo Lake during delivery!

Vibrant costumes flashed and undulated to pulsating drums and clashing cymbals. Dancers appeared to be in trance-like states, their faces shadowed by grotesque demonic masks and ornate hats adorned with tiny skulls as they whirled and dipped in unison. Cham is a ritual dance that depicts the life events of Padmasambhava, or Guru Rinpoche, one of the holiest figures of Buddhism and the first transmitter of Vajrayana teachings to these lands. Unfortunately the sub-par sound system constantly distorted and cut out, not doing justice to the beautiful Tibetan dance and instruments. The rusty generator rumbling off to the side also drowned out the more timorous singers and musicians as they performed ancient renditions. At times I wished these pesky bits of technology had somehow mysteriously fallen into Phoksundo Lake during delivery!

On a hillside I spied Thinle, the stoic hero of Caravan (Himalaya), a film depicting the hardships of yak herders as they cross through the treacherous mountain passes of this region. Sporting the same scruffy goatee, nappy felt hat and red braid that he wore in the movie, he wasn’t too difficult to spot. Well-known by both Nepalis and foreigners, Thinle was catapulted to international fame overnight and was often cast into an unwanted spotlight by tourists wishing to get in a word or photo op. At times he slipped off to his tent where he could relax in privacy with his family.

He was a bit wary of me at first given that in the past kuires had profited greatly from his image without him receiving much in return, but warmed up when I visited his tent with a plastic jug of the local rakshi. He poured me a cup as I scrolled through photos I had taken during the festival. ‘All of these people come here to take pictures of me, but I don’t even own a camera,’ he sulked as he looked through my camera’s viewfinder. ‘It seems that everyone benefits from my photos but me.’ As much as I yearned to get a picture, I refrained for fear of objectifying him and becoming another “profiteering tourist” in his eyes.

The bow & arrow competition followed soon thereafter. After receiving a blessing from Rabjam Rinpoche, the archers quickly took position to try and hit the distant target with much zeal. Some were lucky, but many arrows thudded into the ground before they met their mark. A playful child darted through the crossfire amidst screams from startled women, but was scooped up into her mother’s bosom before any damage was done.

Horse stunts captivated the audience. No one could touch the horseman from Mustang, who easily surpassed everyone with his flair and showmanship. He precariously bent over his mount as he galloped, his head inches from the ground, snatching up kataas and one-rupee notes to the cheer and jaunts of onlookers. After the rupees were exhausted, others tried to goad the godaas into tossing a spare dollar or two onto the field, which confirmed how extensive the universal reach of US dollars had become. Would he also accept Visa?

The finale was the horseracing, the main event. Opinions differed as to the parameters of the course, but after a wobbly start the horses barreled off towards the first mark, hair braids and hats flying in the afternoon breeze. After a few turns across the rocky terrain they were in the home stretch, whooping and whipping hindquarters as their steeds glistened and frothed in full gallop. More confusion followed as to who had actually won, but in the end all of the horsemen strode into the cheering crowds with shiny ribbons and broad smiles.

All the while pilgrims performed kora, or circumambulation, around Crystal Mountain, the spiritual powerhouse of Shey, silently reminding everyone of the underlying purpose of the festivities. Muffled voices and footsteps faded in and out of my dreams at all hours of the night as they shuffled through the maze of tents and onto the path leading towards the mountain. The more kora performed, the greater merit built up for the next life. Increasing the dharma for sentient beings: this is what it was all about, this is why everyone was here. As long as time kept ticking, I had no doubt that kora would continue.

Fortunately cell phone reception has not yet reached Shey, but every stray battery had a cluster of phone chargers with cheap Nokias clinging to it like a swarm of electronic parasites. Most belonged to porters and guides who primarily used them to play their music, but some occasionally wandered up hillsides in search of a weak signal. Transistor radios hummed tinny Hindi songs over marathon card games. Solitary bands of light and laughter emanated from tents as darkness encroached. Although I quietly accepted the advent of electricity, I silently hoped that I would never live to see the day a cell phone tower found its way up here!

Technology may not have overloaded Dolpa yet, but the tipping point seemed near. Everywhere I went plastic water bottles and candy wrappers littered the ground. Latrines dotted the massive campgrounds, but were constantly relocated because holes were not dug deep enough. It would take at least a year for the little stream to flush out this year’s sewage, but next time there might be more people. At times I wish Dolpa never saw a cell phone or piece of plastic, but I realized that everyone is headed into the modern world whether they like it or not. Let’s face it – progress is a messy business, especially up here in such a harsh yet fragile landscape.

Innovation has recently allowed many to catch a glimpse of this magical world, opening the floodgates to a booming tourist industry, yet with technology comes consequences. Each of us shares a responsibility to tread lightly, for Dolpa and “the people of the west” are easily susceptible to change. Himalayan environments cannot endure massive numbers of visitors, and its people should be treated with respect, not gawked through camera lenses as if they were animals in a zoo. Like hidden relics that have suddenly been exposed to the elements, bits and pieces of tradition are steadily eroding away in Dolpa, but if managed properly, this land and people can withstand the growing pains of technology.

The last night I watched a band of women singing folk songs in the dying shadows, their arms clasped together in a circle as they swayed to and fro to the rhythm. As night enveloped them a few flashlights popped to life. I closed my eyes and imagined myself transported back into time, listening to the same centuries-old songs on the same spot of ground. Even in the age of flight, electricity and plastic it wasn’t difficult to lose myself in timeless tradition.Not much has changed up here, and if we’re careful it never will.