Figure 1. The fierce and protective Tibetan mastiff, guardian of homes and yak herds in Mustang and Dolpa (photograph by D. Messerschmidt).

Author’s note: the following story is excerpted from an account I published in Dr. Don Messerschmidt’s 2010 book, “The Big Dogs of Tibet and the Himalayas: A Personal Journey” (Orchid Press, Bangkok). The story was written from field notes and experiences gathered when I was living in the lower Mustang (Jomosom/Muktinath) region of Nepal in the early 1980s, working for a large USAID/His Majesty’s Government conservation project. Included here are the stories about the Tibetan mastiffs of Mustang and Dolpa that I heard from a close friend and trekking companion, Chokgya Lama of the Tashiling Tibetan Camp, Pokhara. The article has been shortened from the original, and updated at the end based on a visit to Pokhara I made in 2019 in search of Chokgya. Special thanks to Don for permission to use sections of the original manuscript for this article, as well as for the use of his beautiful photographs of Tibetan mastiffs. Readers are encouraged to pick up their own copy of “Big Dogs of Tibet and the Himalayas” for a fascinating collection of stories about these little known, but vastly important, friends of the Himalayan high country.

If you mention Mustang or Dolpa to most people in Nepal, it nearly always elicits excited descriptions of the ‘thulo kukur’ or ‘Bhoté kukur’ (Nepali for ‘big dog’ and ‘Tibetan dog’, respectively) that inhabit these regions. The dogs protect villages at night, guard and herd the yak and sheep, assist their masters in hunting tom (Tibetan bear), lau (or lawa, musk deer) and na (blue sheep). They also chase away bandits, and have been used in warfare, possibly for thousands of years. They are most often described as “fierce and dangerous” animals that “will attack any stranger coming near.” This is the Tibetan mastiff--a powerful and practically fearless breed of dog, highly prized by the people of northern Nepal and cautiously respected by all others.

Figure 2. Mastiffs are often chained during the day, which some think can lead to their aggressive behavior towards strangers (photograph by D. Messerschmidt).

The mastiffs of Mustang and Dolpa are large dogs, with males often reaching weights of 44 to 55 kg (100-120 lbs). They are characteristically square-headed with massive jaws, and have long, thick hair, a distinctive black-and-tan (sometimes all black, or golden) color, with a bushy, curling tail. Their presence clearly marks the transition from middle hill Nepal to the Buddhist realms of northern Nepal and Tibet, as one treks northward through the mountains along ancient trade routes. One sees smaller, apparent cross-breeds at the transition points in lower elevation towns and villages, and larger, more purebred mastiffs further north at higher elevations. Because of their great importance in the pastoral economy, mastiffs are treated with deference by their owners here, in stark contrast to the attitudes toward common village dogs of the lower hills.

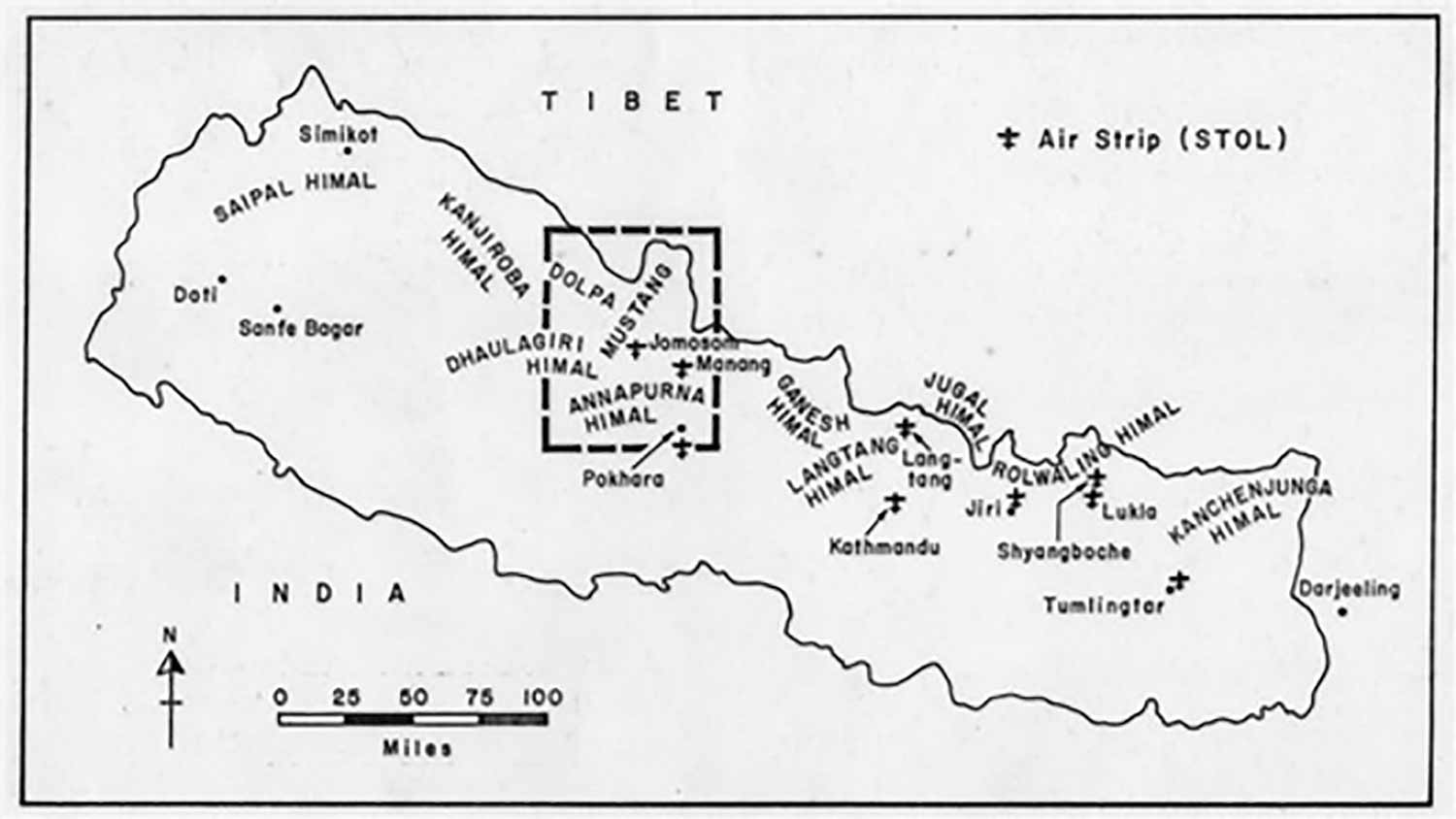

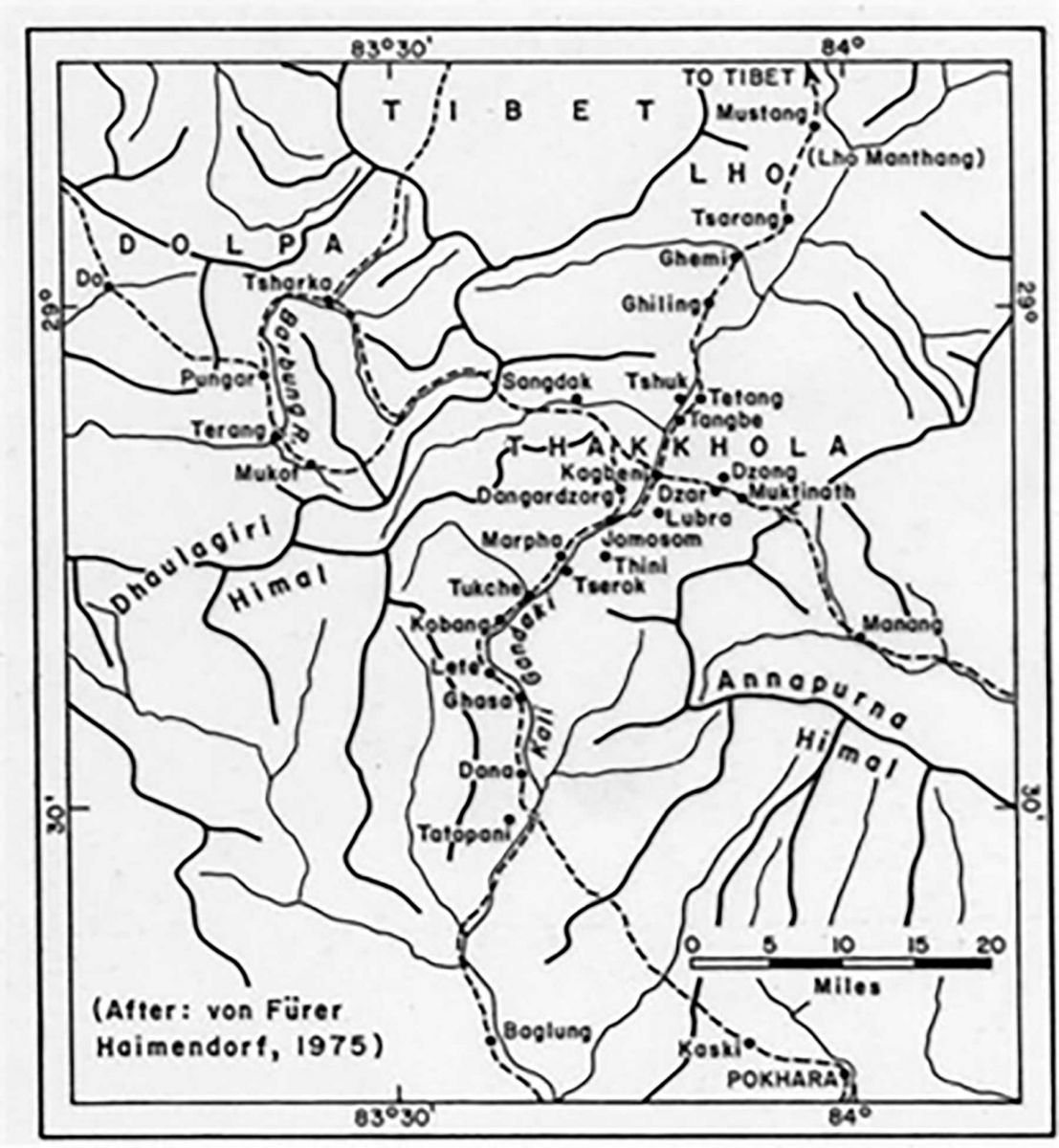

In villages, the dogs are chained during the day, which tends to encourage viciousness, and let free to roam the alleys by night, which induces fear in all who venture out after dark. They are a particularly strong deterrent against intruders in the walled villages of upper Mustang, from Kagbeni north to Lo-Manthang, and in Tibet, where escape routes are practically non-existent and all doors are firmly bolted at nightfall. Tibetan mastiffs (and related dogs of mixed breed) also discourage any unnecessary wanderings in the more dispersed villages of lower Mustang in the Thak Khola region, from Kagbeni south to Ghasa (Figures 3 and 4). For example, in the 1980s while I was working on a conservation project in the administrative center of Mustang District at Jomsom in Thak Khola (the valley of Thak), many a jolly late-night session eating momos and drinking raksi with my Nepalese colleagues in the local Thakali lodges was cut short by the knowledge that the mastiffs kept in the nearby Nepal Army camp would be unchained at 10:00 pm. The dogs effectively enforced this informal night curfew, as by 9:45 we were all safely home.

Figure 3. Location of Dolpa and Mustang within the Nepal Himalaya (see Figure 4 for detail of the blocked area).

Figure 4. Eastern Dolpa and Mustang District in the pre-road 1980s.

Even during the day, the mastiff guard dogs are a source of concern to most travelers. The naturalist and travel writer, Peter Matthiessen, in describing his search for the elusive snow leopard in Dolpa in the 1970s, observed that the dogs are “so fierce that Tibetan travelers carry a charm portraying a savage dog fettered in chain; the chain is clasped by the mystical ‘thunderbolt’, or dorje, and an inscription reads, ‘the mouth of the blue dog is bound beforehand’.” Matthiessen then mentions a rather typical account of his and naturalist companion George Schaller’s efforts at thwarting one such “blue dog” attack, and for the rest of their journey through Dolpa he writes, “I never walked without my stave again.”

Mastiffs have also traditionally been used as guard dogs for the many yak and sheep herds of Dolpa and Mustang. Yaks are usually grazed in the high pastures over 3,675 m (12,000 ft) above the villages. Wolves, bears, lynxes, jackals and both spotted and snow leopards inhabit many of these remote regions, and the mastiffs play critical roles in the protection and herding of yaks, and as companions to the isolated yak herders.

.jpg)

Figure 5. Thinigaon, overlooking the Jomsom airstrip, in the pre-road, pre-electricity days of the early 1980s (photograph by A. Byers).

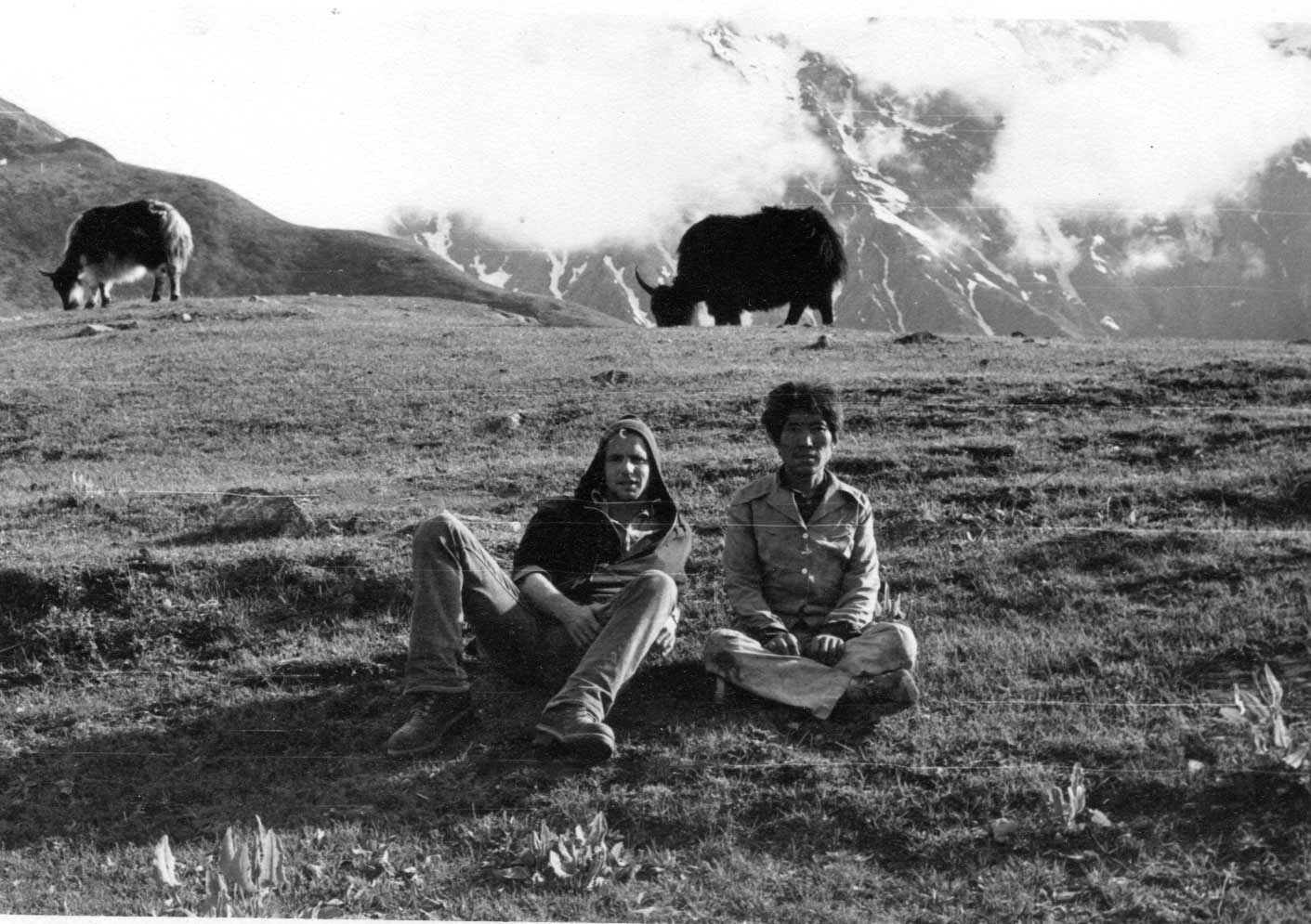

Chokgya Lama’s dogs: Much of my information concerning mastiffs in Dolpa was obtained from Chokgyel Lama (‘Chokgya’ for short), a former yak herder from a village near Tarakot who later moved to the Tashiling Tibetan refugee community at Pokhara, in Nepal’s middle-hills. Over the years, Chokgya and I trekked and worked together throughout lower Mustang and what is now the Annapurna Conservation Areas, and he was a storehouse of practical information regarding life in the mountains. He was born in Dolpa around 1940, and until he was 20 years old he tended the family yaks, ploughed his brother’s fields, cut firewood and accompanied his brothers on trading excursions to Jumla in far western Nepal, and to Tibet. His appreciation and respect for the hard-working mastiffs frequently surfaced in accounts of his early years in Dolpa. For example, Chokgya told me that from the time he was 12 he stayed in the goth (pastures) herding yaks where his only companions were two large dogs. “In Dolpa,” Chokgya said, “it is very difficult to see other people because the region is so remote, and people so few. Once I was in the pastures for four or five months and never saw another man. During this time the dogs were very good friends and were especially useful animals, especially for protecting yaks. I would feed them tsampa (ground, roasted barley) and water curd (buttermilk), and from time-to-time would feed them meat.”

Tsampa, butter and churpi (hard cheese) are the staples of most Tibetan people, and yak herders will carry up supplies of tsampa, cheese and spices to the pastures. They are also entitled to eat all they wish of the milk and milk-products from the herds they tend, in addition to the meat of a winter- or predator-killed yak -- thus the “time-to-time” schedule of feeding meat to the dogs. For Chokgya, the best friend of the yak herder was a good dog. “I had two,” he said, “one for leading the herd when we changed pastures, and one for guarding. The first would always be at the head of the herd, and the second would stay behind to bring in the stray yaks and also to protect them.”

Chokgya claims that the lead dogs actually guide the herd to new pastures. I have not seen this, but have witnessed the dogs participating in the rounding up of stray yaks during the hours of dusk when they are brought into the camp area for the night. The herdsman’s yak-hair sling (shakpo pumba), however, seems to be more useful than the dogs for bringing in the yaks. The gothalo (herder) expertly lobs a large stone in the general direction of the truant yak, which induces it to start towards the camp. The dogs will then finish the job by running behind the yaks and herding them back to camp. “Sheep and yaks will listen to a dog,” Chokgya continued. “When he barks or gives a warning they will come together. At night they know the dogs will protect them.”

One of Chokgya’s more intriguing stories concerning his mastiffs involves an encounter with a mithé (‘jungle man’, another name for the yeti) when he was 15 years old. During the early hours of a foggy morning, the dogs began to bark and run around the camp, whereupon the yaks began to group together in a protective circle. The dogs appeared to be crazed with both fear and anger. Shortly afterwards Chokgya heard the distinctive, high-pitched “che-che-che” -- the whiney cry of the mithé -- and he remembers a “very bad smell.” A large man-like image did appear momentarily out of the fog, which Chokgya fired at with his old muzzle-loader. The dogs took off in pursuit of the creature, but returned a short while later, exhausted. Chokgya found a pool of “very black blood” nearby a stream where the creature was seen. I’ve found that such stories are common throughout much of the Himalaya, and remain a mystery in terms of what the mithé may or may not be.

“There are two types of dogs in Dolpa,” Chokgya continued. “One is the small one, and the other the big one. The big one is not so good for hunting. The big dog is good for guarding yak and sheep.” The hunting dog, the smaller one, locally called Sheuke (Tibetan Sha-kyi), is colored black and white, and a good one could cost a thousand rupees in the early 1980s. I’ve since learned that there are actually five distinct breeds of Tibetan dogs recognized by international breeders that include the Kyi Apso, or “Tibetan Bearded Dog” (a herding and village guard dog, but with a friendly disposition compared to the mastiff), the Lhasa Apso (a small house dog), Tibetan Mastiff (of interest here), Tibetan Spaniel (another small house dog), and the Tibetan Terrier, in addition to the Sha-kyi hunting dogs that Chokgya used.

Figure 6. The author (left) and Chokgya (right) ca. 1981, high in a yak pasture above the Kali Gandaki river (photographer unknown).

“In Dolpa we used to go hunting with the help of the dogs.” Chokgya said. “The dogs would chase the lau (musk deer) and na (blue sheep) through the mountains, sometimes into traps, and sometimes until the deer were so tired that we could simply walk up and shoot them. There are many hunting dogs in Dolpa, male and female. The females are much faster and better than the male dogs. In Dolpa it is the poor people who mostly go hunting; the rich don’t go because they have yak and sheep to eat.”

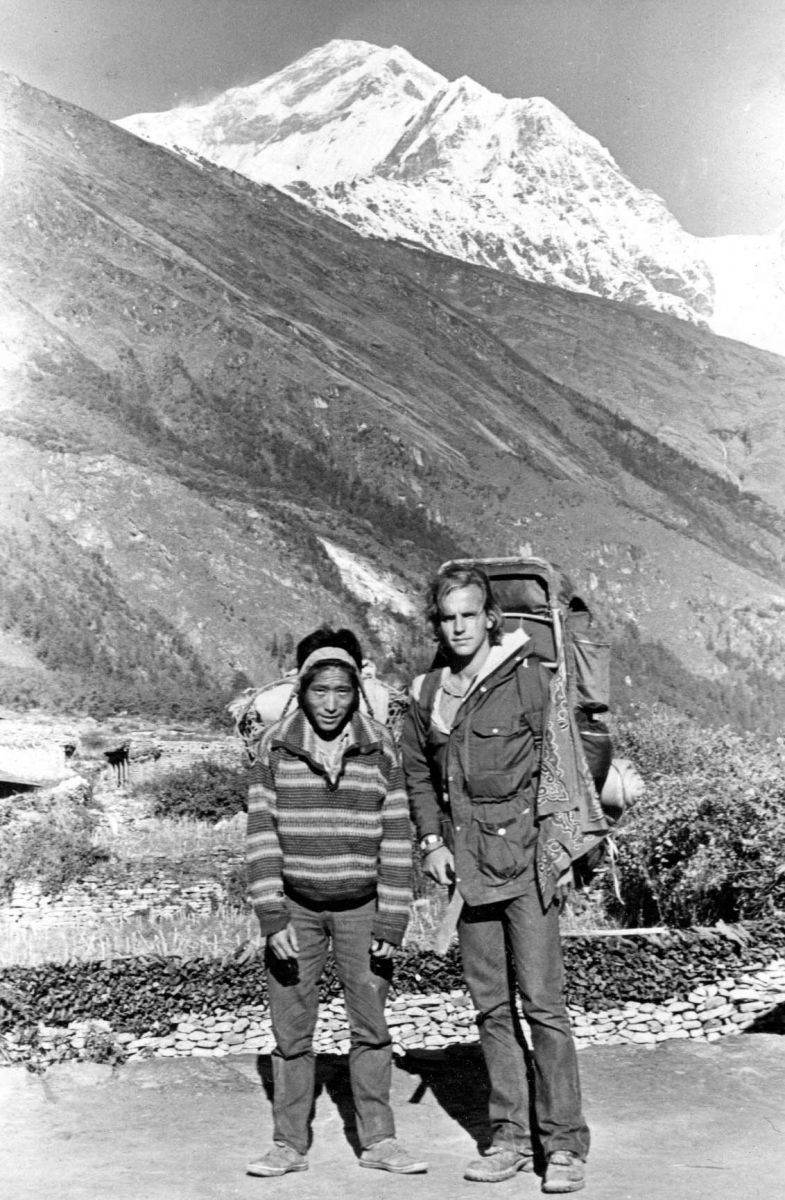

Chokgya and I spent many months together in the yak pastures of lower Mustang over a period of ten years (during the 1970s and 1980s), and had ample occasion to meet many Tibetan mastiffs. Some, as in the yak pasture above the village of Marpha in Thak Khola, were nothing less than vicious upon seeing intruders such as ourselves. Chokgya’s skill with the braided yak-hair sling was greatly appreciated at these times. On another occasion, while climbing in the Annapurna Sanctuary in the early 1980s, I witnessed a young Sherpani porter from another expedition being severely bitten in the leg for straying too close to a herd. Some dogs we met were quite timid, and were kept more for sounding alarms than for attack purposes. By and large, they had the characteristic black-and-tan markings, although several golden mastiffs were seen, as well as much smaller dogs (the size of Tibetan terriers and Lhasa Apsos), probably kept more for company than for work. Regardless of their temperament, all were treated with a quiet affection and respect by their owners.

Figure 7. The braided yak hair sling is not only a valuable weapon and deterrent against unfriendly dogs and predators, it is also used by yak herders to manage the movements of yaks. Generally all that is needed is a gentle lob of a stone to send a yak in the herder’s preferred direction of travel (photograph by A. Byers).

Tukché and Lete are villages in Thak Khola known for their superior mastiffs. There, a healthy male puppy, the pick of the litter, sold in the early 1980s for around 250 rupees, and considerably more to foreigners along this popular trekking route. (Rs. 250 was approximately $10.00, a considerable sum at that time; for some nomads, a prize Tibetan mastiff was considered to be equal in value to a full grown yak, or a good horse.) The walled town of Lo-Manthang, the former capital of Mustang, about three days walk north of Jomsom, is also famous for its mastiffs. The large, ‘pure dogs’ bred there, especially those belonging to the family of the former Raja of Mustang, are highly prized, and the people of Thak Khola, and even of Kathmandu, frequently make arrangements with traders to deliver puppies to them.

As noted, the mastiffs’ viciousness is probably more a result of how they are kept and of their conditioning. As with any breed of dog, ferocity comes from being tied up throughout the day while strangers pass by, or from living in remote places combined with their innate territorial instincts for which these dogs are so well known. Certain dogs kept only as pets, however, are quite affable and appear to be excellent (although somewhat aloof) additions to the large and busy households of the mountain people.

The big dogs of Mustang and Dolpa play integral roles in the economic survival of the local people. By comparison with other regions of Nepal, food, fuel, water and arable land are very scarce here, and roving bands of brigands are still somewhat common. Those resources that do exist must be zealously guarded and protected--functions performed well for countless centuries by Tibetan mastiffs.

Postscript: Pokhara, January 2019: When my contract finished in 1982 and I left the Kali Gandaki region for graduate studies in the US, little did I know that I was to spend a lifetime exploring and researching a number of Nepal’s other Himalayan treasures, such as the Khumbu, Makalu-Barun, and Kanchenjunga

Figure 8. Tibetan mastiff at rest (photograph by D. Messerschmidt).

regions, among others. But for all this time in Nepal I never returned to Pokhara until January of 2019, some 37 years later, to look for Chokgya. I knew that his home had been in the Tashiling Tibetan Refugee Camp with his wife and young son, Kongma, in a small row house made of whitewashed mud and stones.

Needless to say, a lot had changed in Pokhara since the early 1980s. Much of the snow and ice of the Annapurnas was gone, and the range itself was usually obscured by the dust and smoke of the Asian Brown Cloud. Ultralights and paragliders buzzed noisily overhead every morning, and the once sleepy little town was now one of Nepal’s larger cities. The lakeside lodges and outdoor cafes that I used to stay at, catching the flight to Jomsom the next morning, had been replaced with wall to wall restaurants, amusement parks, and endless curio shops. But the food was much better than that of the 1980s, and even the pies and cakes that had drawn many a hippy overlander to the place during the 1960s and 1970s had improved.

The Tashiling Camp had changed as well, now with modern streets, homes, outdoor cafes filled with young people, and thriving businesses as opposed to the fairly destitute look I encountered in the 1970s and 1980s. And for some reason I thought that Chokgya would still be there. But when I started asking around I was told that no, both Chokgya and his wife had passed away. When I asked when, nobody really knew, except that “it was a long long time ago.” I did meet his son, Kongma, now a middle aged man, but he didn’t remember me.

Things have changed for the Tibetan mastiff as well. These days there is less reliance on animal husbandry as a way of life in Dolpa and Mustang than there used to be, partly because of labor shortages caused by outmigration to the Middle East, and partly because Nepal is changing in ways we could hardly have imagined back in the 1980s. The yak herds and the mastiffs that guard them are still there in the high pastures, but their numbers are dwindling, mostly because of a decreased demand for livestock products such as cheese, milk, hair, and hides. But I still wouldn’t recommend a walk through the streets of a remote village in Dolpa or Mustang late at night.

Suggested Reading

Messerschmidt, D. 2010. Big dogs of Tibet and the Himalayas: a personal journey. Bangkok: Orchid Press. Rohrer, A. and Flamholtz 1989. The Tibetan mastiff: legendary guardian of the Himalayas. Centreville, AL: OTR Publications.Taylor, D. 1993. Meet the rare mountain dog of Tibet. Dog World. November, 1993

Mountain geographer Alton C. Byers, Ph.D. is a Senior Research Associate and Faculty at the Institute for Arctic and Alpine Research (INSTAAR), University of Colorado at Boulder; Explorer and Grantee of the National Geographic Society; and a Senior Fellow at The Mountain Institute.

Figure 9. Chokgya (left) and the author (right) in 1973, Kali Gandaki valley, Mustang District.