Her husband went to the mountain and she would transport expedition equipment to the base camp on her yaks. Traveling to the Everest base camp is an adventure for most but for women like her it was like going home. One time she even went there carrying her 7 month old baby and spent a night there.

When you look for definition of the word "Sherpa" in a dictionary, it reads “a member of a Himalayan community living on the borders of Nepal and Tibet, renowned for their skills in mountaineering.” Sherpas are synonymous with the mountains but still they don’t really get the credit that they truly deserve because international mountaineers have always eclipsed them and their help in summiting Everest. After the very first Everest summit in 1953, Edmund Hilary was knighted and got plenty of accolades, while Tenzing Norgay had to settle for a George Medal for "acts of great bravery." Very few even think of the women in the Sherpa community. Last year I watched a documentary film titled "Sherpa," which explored the journey of Phurba Tashi’s attempt to summit Mount Everest for a record twenty-second time in 2014 that ended when the worst ever single disaster on the mountain claimed the lives of 16 Sherpas. It was an exhilarating tale of the lives of the faceless heroes of the Himalayas, demanding recognition and respect. In an interview with Sherpa’s director, Jennifer Peedom, she mentioned one of the reasons she made the film was how little of their stories were told in documentaries and movies. The film not only showed the amazing job the Sherpas did to get climbers to the summit but also briefly touched on the troubles faced by the women and children of the Sherpa guides who lived risky yet fascinating lives. In a scene in the film, we can see the desperation of Tashi's wife and family watching him risking his life on Everest for money. It's a familiar tale of almost all the families in the Sherpa community.

When you look for definition of the word "Sherpa" in a dictionary, it reads “a member of a Himalayan community living on the borders of Nepal and Tibet, renowned for their skills in mountaineering.” Sherpas are synonymous with the mountains but still they don’t really get the credit that they truly deserve because international mountaineers have always eclipsed them and their help in summiting Everest. After the very first Everest summit in 1953, Edmund Hilary was knighted and got plenty of accolades, while Tenzing Norgay had to settle for a George Medal for "acts of great bravery." Very few even think of the women in the Sherpa community. Last year I watched a documentary film titled "Sherpa," which explored the journey of Phurba Tashi’s attempt to summit Mount Everest for a record twenty-second time in 2014 that ended when the worst ever single disaster on the mountain claimed the lives of 16 Sherpas. It was an exhilarating tale of the lives of the faceless heroes of the Himalayas, demanding recognition and respect. In an interview with Sherpa’s director, Jennifer Peedom, she mentioned one of the reasons she made the film was how little of their stories were told in documentaries and movies. The film not only showed the amazing job the Sherpas did to get climbers to the summit but also briefly touched on the troubles faced by the women and children of the Sherpa guides who lived risky yet fascinating lives. In a scene in the film, we can see the desperation of Tashi's wife and family watching him risking his life on Everest for money. It's a familiar tale of almost all the families in the Sherpa community.

One of the women who lost her husband in the tragedy was Nima Doma Sherpa, a trekking guide by profession herself. Her home is on the way to Everest Base Camp; her heart rests on the mountain. Her closest friend is Furdiki Sherpa, who transports equipment to base camp on her yaks and whose husband also lost his life on Everest in 2013 in a similar manner at the Khumbu Icefall.

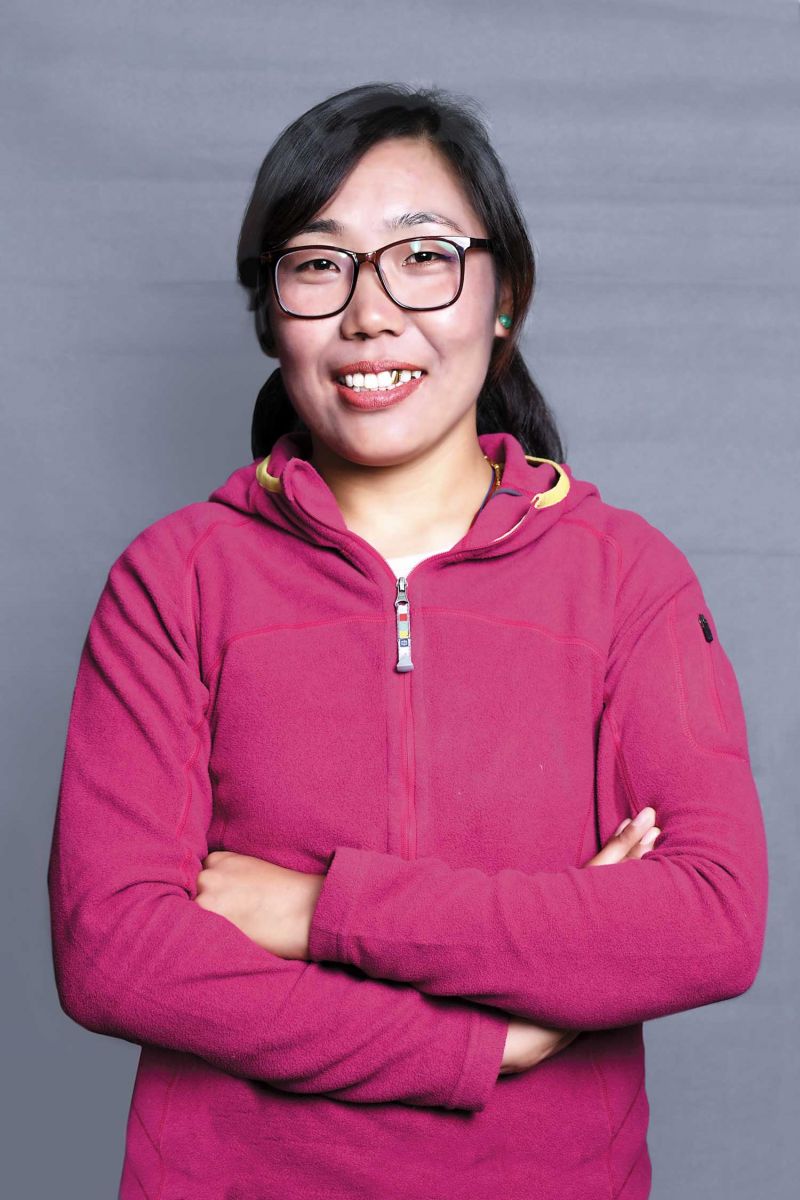

Nima Doma Sherpa

"My childhood inspiration was my father, Ang Chumbu Sherpa, who worked as a trekking guide and even reached the summit," said Nima, remembering her childhood. She was born in Khumjung, a village in Solukhumbu District in North-Eastern Nepal. Nima is the youngest of three siblings and the most educated in her family, having studied till grade nine in Sir Edmund Hilary School. She was a very daring child and worked as a trekking guide from her teenage years; she got married when she was just 18 and gave birth to her first child when she was 22.These events halted her career for some time.

Unlike many of her friends, her marriage wasn't arranged. She married her high school sweet heart, Tshering Wanchu. "Me and my husband were from the same village and we grew up together. We studied in the same school, we used to play in the fields and watch the stars late at night. That's how we fell in love. "He was a very good husband. He was very supportive and caring. Despite working very hard to earn a living, he also lent a hand in the household chores. When I was tired, he cooked the meal and washed the children’s clothes."

Unlike many of her friends, her marriage wasn't arranged. She married her high school sweet heart, Tshering Wanchu. "Me and my husband were from the same village and we grew up together. We studied in the same school, we used to play in the fields and watch the stars late at night. That's how we fell in love. "He was a very good husband. He was very supportive and caring. Despite working very hard to earn a living, he also lent a hand in the household chores. When I was tired, he cooked the meal and washed the children’s clothes."

Before he went on his final trip, Nima's husband called home and talked to everyone in the family. "It was like a goodbye call, it was as if he knew what was about to happen. He told me not to work very hard and to look after the children. He said he would come back after a month.” On the morning of the fatal day, she was having a cup of tea in her husband's cup. "The cup cracked and broke, which is considered a bad omen. There was a lot of noise in the neighborhood that morning. By the time we went to find out what was happening, there were already rumors that many people had died on Everest because of a deadly avalanche." Her husband had passed away at 6 am at the Khumbu Ice fall, after the avalanche, but she got the news only at 12 pm, from one of his close friends.

After the avalanche, Sherpas announced they would not work on Everest for the remainder of the year as a mark of respect for the Sherpas who had lost their lives. The following year, an avalanche triggered by a powerful earthquake killed several climbers. These lethal avalanches halted climbing for two seasons. Meanwhile, two seasons was what Nima needed to grieve her loss and get back on her feet. She had lived as a home maker since she got married. But after the tragedy, she got back into trekking.

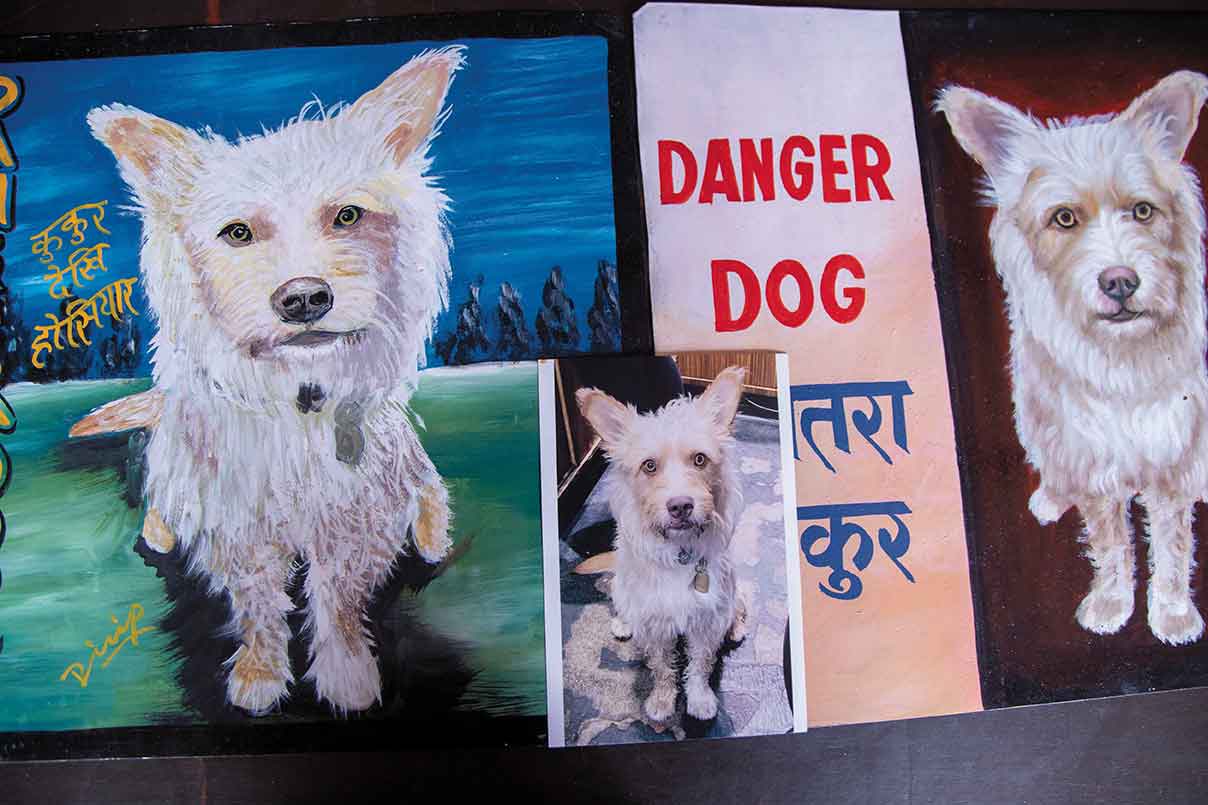

Furdiki Sherpa

Like Nima, Furdiki had mountains in her genes. Her father was Ang Nima Sherpa, popularly known as "The Icefall Doctor." He specialized in the Khumbu Icefall, a glacier mass which is more than 500 feet deep. Many mountaineers regard this as the most hazardous part of the Everest climb. It was considered impossible to cross when the British first discovered it. Ang Nima Sherpa and his team of Sherpas were the ones responsible for mapping the route up in the Khumbu Icefall, from the base camp to camp 1 and then to camp 2. Like a surgeon specializes in using surgical instruments and tools, the Icefall Doctor had mastered ladders, ropes and ice screws.

Furdiki Sherpa was also born in Khumjung village. She was the eldest child in the family and had a lot of responsibilities. "My siblings were small and my parents were always busy with work so I never had the opportunity to step inside a school." Furdiki used to go to the base camp often with her yaks, transporting expedition equipment. "When I was young, every day was an exciting adventure. I used to work all day and in the evenings, I spent time with my friends, having conversations about life and making fun of each other." Her relationship with her friends has always been special. "Even if I didn't have anything, if my friends needed help, I was there for them like they were there for me."

Furdiki Sherpa was also born in Khumjung village. She was the eldest child in the family and had a lot of responsibilities. "My siblings were small and my parents were always busy with work so I never had the opportunity to step inside a school." Furdiki used to go to the base camp often with her yaks, transporting expedition equipment. "When I was young, every day was an exciting adventure. I used to work all day and in the evenings, I spent time with my friends, having conversations about life and making fun of each other." Her relationship with her friends has always been special. "Even if I didn't have anything, if my friends needed help, I was there for them like they were there for me."

She met with her husband Mingma Sherpa when he came to Khumbu from Solu to construct a house. "My husband was in construction work. The man who made houses made a home for me." Her husband and her father were more like friends. They had spent all their lives in the mountains and could relate on many things. She got married when she was 19 and had her first child when she was 21.

Neither she nor her husband had received an education, so they faced a lot of challenges. Her husband was also an experienced guide in addition to being a carpenter. He went to the mountain and she would travel to base camp with her yaks, carrying equipment. "Traveling to base camp was never unique to me. One time I even went to there carrying my 7 month old baby and spent a night there". Her father died peacefully in his home and her husband, who had taken over the title of the "Icefall Doctor" died few months later in the Icefall itself in 2013.

For many people, the mountain is nothing but wilderness but for these women it's not only their workplace but a site for worship. The women see the effects of climate change more than any researcher. "We see the mountain every day from morning to nightfall. We can clearly see Everest losing its layer of ice and snow every year. When we were young, it was covered in snow throughout the year, now it's becoming darker every year", said Furdiki. And it's not just global warming that has the women worried; the increasing pollution on the mountain is another concern. There are tonnes of garbage left behind by the climbers every year which they see as a serious problem. "We don't understand politics much but the government should make sure the mountains are taken care of. The waste should be carefully sorted and carried down." But they remain optimistic as in recent times they see more and more foreigners gathering rubbish before descending.

The two women are very vocal about the lack of recognition of the Sherpa climbers. Mountaineering is a career that's not without risks and the women believe that people who die in the mountains should be treated like martyrs and their bereaved family should receive some compensation or benefits like the families of soldiers who die in action. After the 2014 tragedy in Everest, all of the women who lost their husbands came together. "Some of us became real close and decided to do something for single mothers.”

"I mourned his death for two years, but then I realized I had to do something for single women across the country," said Furdiki.

Nima and Furdiki want to show to the world what single women are capable of. Both of them were in the trekking business, both lost their husbands on the mountain. The tragedy brought them together and they were two women who shared the same passion towards the mountain. "We decided that the best way to put our message across to the world is for us to climb Everest. So we embarked on the journey two years ago," said Nima.

Nima and Furdiki had the courage, strength and ambitions but they needed help to achieve their dream. They met a man named Ang Tshering Lama who understood their vision and told them to join Khumbu Climbing Center (KCC) if they really wanted to go for it. They became part of the intense training program and then went for 45 days of training in NMA (Nepal Mountain Association).

They dream of climbing Everest but lack of adequate financial support is their biggest challenge. They have been collecting money so that they can fund their expedition. Many people have helped them along the way. "The Pasang Lahmu Village Development Committee helped us with guide training. While we learnt ice rock training thanks to NMA. We have also met some amazing people like journalists Doma and Nawang Sherpa who have helped us a lot." They want to climb the mountain not only for themselves but for other widows and single mothers. "We hope to start an organization for their benefit after returning from the expedition. We have  been training a lot for it, thanks to Himalayan Sherpa's director."

been training a lot for it, thanks to Himalayan Sherpa's director."

To achieve their dreams, they have done intense training, reaching Chulu East Peak in 2018 and Island Peak which is around 6189 meters high. Their children remain worried. Nima has a son and a daughter. Her eleven year old son, who wants to be a doctor, knows what happened to his father, but the daughter is too small to understand. "When he saw me packing my bags with equipment, he asked me what I was doing. I told him I was planning to climb the mountain so he got worried. He said he didn't want me to end up like his fathe.r. Once he saw her in the news, though, he realized Nima was doing something special. He told his friends and teachers the next day about his brave mother.

Furdiki has three daughters aged 20, 17 and 14 years respectively. "My daughters initially didn't want me to take the risk but once they saw me on the news, they were very supportive. They send me messages often to know about my whereabouts and when I am doing the climb."

The women living in the mountains have undeniable bravery and abilities but haven't always received the opportunities to go beyond their traditional roles. Women like Nima Doma Sherpa and Furdiki Sherpa prove they are no different to male mountaineers. There is no difference among men and women climbers when it comes to skill, endurance or passion and when you see a climber in mountaineering attire, face covered with a mask, it’s even difficult to tell which gender the mountaineer belongs to. Up there, everyone’s equal.