Perceval Landon, the British writer, journalist, and traveler, visited Patan in the 1920s and was enamored by its beauty. “As an ensemble the Durbar Square in Patan probably remains as the most picturesque collection of buildings that has ever been set up in so small a place…” he says in his two-volume book, Nepal.

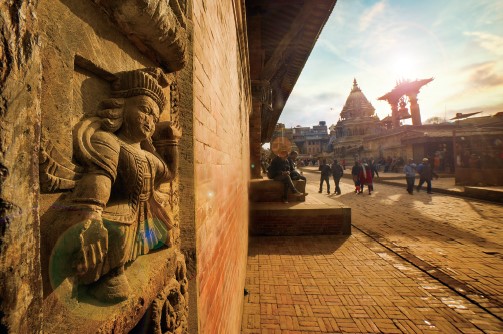

And you cannot agree with him more. You step onto the red brick pavement of Yala Lyaku—colloquial Newari for Patan Durbar Square—and it’s as if a broad, linear space displaying the best of Newar art and architecture welcomes you with open arms. On your right stretches the palace. On your left are lined eight temples.

The Krishna Temple, perhaps the finest specimen of stone monument in the Valley, and architecturally similar in appearance Nisantaneshwor Temple, will arrest your attention right away, as will the Bhimsen Temple on the northern edge of the complex, with its finest carvings of metalwork and woodwork. The gilded statue of Yog Narendra Malla, kneeling down, his hands folded, with a Naga canopy over him and a bird perched on it, and the statue of Garuda, both placed on top of tall stone pillars, are so imposing and intrinsic parts of the complex that you cannot miss their presence. Neither can you remain without being enthralled by the magnificence of the colossal stone bell on a tall stone platform in front of Taleju Temple.

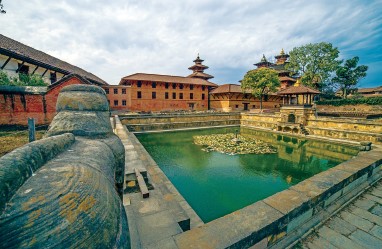

The entrances of all the temples face the facade of the palace buildings on the other side of the paved path. The doors on the facade of these buildings open to the three main chowks (courtyards)—Keshav Narayan Chowk, Mul Chowk, and Sundari Chowk—that lead to different sections of various wings of the palace. Mul Chowk, the central courtyard, is the largest, and houses the Taleju Temple at its one corner. Sundari Chowk, that lies south of Mul Chowk, is considered the most beautiful of all chowks in the Kathmandu valley. It prides itself on Tusa Hiti, the sunken bath, touted among the finest heritages of stone from the Newar sculptors. Stone statues of Hanuman and Ganesh, and Narasimha, who represents Vishnu’s man-lion form, guard the entrance to this chowk. Massive stone statues of lions, their mouths open in a roar, guard the entrance to the Mul Chowk, while smaller ones guard the entrance to the Keshav Narayan Chowk.

The entrances of all the temples face the facade of the palace buildings on the other side of the paved path. The doors on the facade of these buildings open to the three main chowks (courtyards)—Keshav Narayan Chowk, Mul Chowk, and Sundari Chowk—that lead to different sections of various wings of the palace. Mul Chowk, the central courtyard, is the largest, and houses the Taleju Temple at its one corner. Sundari Chowk, that lies south of Mul Chowk, is considered the most beautiful of all chowks in the Kathmandu valley. It prides itself on Tusa Hiti, the sunken bath, touted among the finest heritages of stone from the Newar sculptors. Stone statues of Hanuman and Ganesh, and Narasimha, who represents Vishnu’s man-lion form, guard the entrance to this chowk. Massive stone statues of lions, their mouths open in a roar, guard the entrance to the Mul Chowk, while smaller ones guard the entrance to the Keshav Narayan Chowk.

If you sit along the steps along the facade of the palace, or on the benches set against the facade of the durbar, you will get a complete view of the temples on the opposite side in one vision. This linear placement of the temples on one side, and the palace on the other side, is an architecturally distinguishing feature of this durbar square from Kathmandu and Bhaktapur Durbar Squares. Such linear placement makes this complex unique, and sitting on one side gives an appealing perspective to the appreciation of structures on the other side of the square.

But, to think that structures themselves are complete would be to partly miss the souls that embody these structures, and so, of the entire durbar complex.

Piety, peeps, jealousy: myths surrounding Patan monuments

Especially if you sit on the benches, and listen to the elderly engaged in conversation, oftentimes you might overhear them relating the legends and myths surrounding a temple or a structure or culture associated with the durbar square. Indeed, every single temple or structure has a tale to tell, or a mystery of its mythology that needs unfolding.

Knowing these myths and stories is crucial to understand and experience the soul of Patan Durbar Square. Of many legends and myths, five stand out most notably. Three of these are related to Siddhi Narsimha Malla, most famous of all Malla kings in Patan, and whose rule is called the “golden age” for the glories Patan’s arts and architecture achieved during this time.

The legend behind the durbar square’s most renowned temple, Krishna Temple, is one. Siddhi was a great champion of yoga and spirituality, and a devotee of Lord Vishnu, one of the most revered deities in the Hindu pantheon. One night in 1636, he dreamt of Lord Krishna, an incarnation of Lord Vishnu, standing with his beloved consort Radha right in front of the durbar, straight from where the golden window lies. Elated and moved by the dream, the devout king had a temple erected at the same spot where the divine couple appeared in his dream. The three-storied temple, with a pinnacle over it, is built in the shikhara architectural style, and its first floor houses statues of Krishna and his consorts, Radha and Rukmani. The beams along the first and the second floors have carvings of the Hindu epics Mahabharata and Ramayana, respectively.

The myth behind the temple of goddess Taleju, the family deity of the Malla kings, is perhaps more captivating. Goddess Taleju descended upon Earth disguised in human form to play dice with Siddhi Narsimha every night, a secret that the king guarded well. This was to arouse the queen’s curiosity. One night, she peeped through the keyhole into the room where they played, and was instantly taken by a feeling of extreme jealousy at the beauty of the goddess disguised in human form. She complained to the king. Learning that her disguise had been discovered, the goddess stopped visiting the king. The king became extremely worried at having failed to keep her secret. Touched by his devotion, the goddess visited him in his dream and consoled him, saying that she would visit him if he wished so, but in different form. She advised him to establish a living Kumari, and she would enter her body.

Adjacent to Mul Chowk, the main courtyard where Taleju Temple stands at one corner, is the Sundari Chowk that houses Tusa Hiti, a sunken bath that is a repository of exquisite stone sculpture, considered among the most treasured heritages handed over from the Malla era. Built in 1647, the bath is surrounded on both sides by numerous deities enclosed by serpents. Around the bath are three rows of alcoves with figures of minutely carved 57 stone deities. And, on the crown of the sprout stands a miniature image of Krishna Mandir outside in the square. On both sides of this replica are various deities. In front of the bath is a giant rectangular-shaped stone platform raised some feet above the ground.

Historians hold disputed views on whether Siddhi Narsimha used the bath for ritualistic ablutions or had it built to satisfy his love of arts, but they largely agree on the purpose of the stone platform. They say that on its top and facing the deities in the bath, the pious, yogic Siddhi Narsimha practiced penance, sleeping on it during the coldest of winters and hottest of summers. The qualities of this devout and spiritually inclined king seems to have passed onto his son Shrinivas and grandson Yog Narendra Malla, both of whom constructed temples and structures that added to the glorious arts and architecture of Patan. Myths surrounding two structures built by Yog Narendra Malla are most captivating.

One of these is the fable of Nisantaneshwor Mahadev Temple, or the temple that robs off child bearing ability. Seeds of jealousy and animosity were sown between the Malla rulers of Kathmandu, Patan, and Bhaktapur when the single Malla kingdom of the valley was divided into three, and the myth of this temple is directly connected to this. A farmer from Patan, who traveled to Bhaktapur to sell vegetables, found a regular customer in its king. When Yog Narendra Malla learnt about this, he exploited this to bring misfortune to Bhaktapur. He had a stone idol of Ku Laxmi, the goddess of ill fortune, sculpted and sent to the Bhaktapur through the vegetable vendor.

Time would reveal to the king of Bhaktapur the cause of the misfortune that eventually befell his kingdom. And how was it possible that, upon learning of the betrayal, he could remain without vengeance? He swiftly sent a message to Yog Narendra Malla that he wanted to gift a beautiful temple to the beautiful Patan Durbar Square. When the latter accepted, he had a temple of Nisantaneshwor Mahadev built. So, even though Yog Narendra had over thirty wives, none of them bore him a male heir. Even today, no one worships in this temple, fearing that it would render them infertile.

The second structure and its myth are connected to this. Heartbroken for not having an heir, Yog Narendra abdicated the throne and left his kingdom. But, before leaving, he said he would return. And to convince his people, he erected his guild statue with a Naga canopy and a golden bird perched on it. He told his people that that as long as the bird stays there, it should be known that he is alive and could return any time.

The second structure and its myth are connected to this. Heartbroken for not having an heir, Yog Narendra abdicated the throne and left his kingdom. But, before leaving, he said he would return. And to convince his people, he erected his guild statue with a Naga canopy and a golden bird perched on it. He told his people that that as long as the bird stays there, it should be known that he is alive and could return any time.

Some historians believe that the king did go into exile in Changu, but that he was poisoned and cremated in Shankhamul on the banks of the Bagmati to the south of the durbar square, his thirty-one wives jumping into the funeral pyre as Sati. Still, the myth has persisted, year after year, and every day until a few years back, his food, bed, and hookah were prepared, just in case he returned. Even today, locals, especially the elderly chatting in the durbar square complex, are seen looking at the king's statue and the bird over him and sharing the tale that he is not dead, and could return any time.

It is myths like these that are so integral to the parts of the temples, monuments, and different structures that make the history of the Patan Durbar Square more engrossing and valuable. And, it is these legends and stories, preserved and passed down from one generation to the next that have ensured that the high arts, architecture, and culture of the Malla period stand proud and tall even two hundred-and-fifty years after the fall of the Malla dynasty.

(Author’s note: The history and myths surrounding Patan Durbar Square have been compiled from numerous sources, including past editions of ECS Nepal, information boards in the square, and various books and scholarly works on the square.)

(Author’s note: The history and myths surrounding Patan Durbar Square have been compiled from numerous sources, including past editions of ECS Nepal, information boards in the square, and various books and scholarly works on the square.)