He realized that the month’s time given to him was too short for such an important work; nevertheless, he sent back a three page report stating that many of the monuments were on the verge of falling apart and that a program to restore historical buildings was needed.

The late King Birendra was crowned King of Nepal in a lavish coronation ceremony on February 24, 1975; although, according to custom, he had already been proclaimed king three years earlier, on January 31, 1972, the day his father King Mahendra passed away. A fortunate offshoot of the time between the proclamation and the coronation was that these three years turned out to be the most important in the history of architectural restoration in Nepal. For it was then that the pioneering work in restoration began with the Hanuman Dhoka Palace, which would be the main venue for what was planned to be the grandest of all ceremonies in Nepal. The list of invitees to this once in a lifetime event was a veritable Who’s Who. Royalty would be coming from all corners of the globe and heads of state of many friendly nations (and who wasn’t friendly with Nepal in those days?). The country had to put its best foot forward and show its finest face. The UNDP had graciously agreed to fund the Hanuman Dhoka Conservation Project.

The late King Birendra was crowned King of Nepal in a lavish coronation ceremony on February 24, 1975; although, according to custom, he had already been proclaimed king three years earlier, on January 31, 1972, the day his father King Mahendra passed away. A fortunate offshoot of the time between the proclamation and the coronation was that these three years turned out to be the most important in the history of architectural restoration in Nepal. For it was then that the pioneering work in restoration began with the Hanuman Dhoka Palace, which would be the main venue for what was planned to be the grandest of all ceremonies in Nepal. The list of invitees to this once in a lifetime event was a veritable Who’s Who. Royalty would be coming from all corners of the globe and heads of state of many friendly nations (and who wasn’t friendly with Nepal in those days?). The country had to put its best foot forward and show its finest face. The UNDP had graciously agreed to fund the Hanuman Dhoka Conservation Project.

John Sanday, OBE

Architect John Sanday was entrusted with supervising the project and he found an able associate in Engineer Hari Ratna Ranjitkar of the Department of Archaeology. Sanday first came to Nepal as a UNESCO consultant in 1970 to make an inventory of monuments of the Valley. He realized that the month’s time given to him was too short for such an important work; nevertheless, he sent back a three page report stating that many of the monuments were on the verge of falling apart and that a program to restore historical buildings was needed. Subsequently, he was requested by Nepal’s Department of Archeology to do something about Hanuman Dhoka. Although the gross neglect around the site distressed him, Sanday accepted the challenging task and set about chalking out a four-phased program. Realizing the urgency of the venture (to be completed in time for the coronation in 1975), he immediately started work on the façade and the main courtyard where the ceremonies were to be held.

John Sanday’s career in Nepal as a restorer began with the Hanuman Dhoka project. He emphasized what he called the use of “appropriate technology” and set up a training program for architects and craftsmen. His work experience in England (including restoration of Chevening House, once owned by Prince Charles and now the Foreign Minister’s residence) stood him in good stead. According to Sanday, the first seismic retrofitting works in Nepal were probably the ones he did at the Hanuman Dhoka towers. He also devised a way to water proof jhingati tiles (local roof tiles). The project lasted five years (1972-1977) and involved about 300 workers including almost 50 wood carvers. About his initial experiences, he commented once in an interview, “At first I was often referred to as the ‘Conversation Architect’. People were so completely unaware of conservation issues.” The only good side to this was that he was free to make his own rules. That was unlike in England where, according to him, “There are very strict guidelines for such work there. Here it was so liberating to be free from similar strictures.”

In 1978, Sanday was approached by UNESCO to stabilize the Swayambhunath structure, which was seemingly falling down the hill because of the shifting hill top. The work involved some “frightening excavations” beneath the two conspicuous towers which led to the discovery that the foundations were on a ledge and so always at the risk of ‘slippage’. He worked on it for a year after which, along with the late Engineer Hari B. Shrestha, he set up John Sanday & Associates and became busy with various other projects including the Brahmayani Temple Conservation Project in Panauti. In the meanwhile, he also became a consultant for the Getty Foundation grant program and travelled the world. He set up the Cambodian monument program and used his Hanuman Dhoka experience on restoration works at the Angkor Wat. He was associated with the foundation for three years after which he took on a conservation project in upper Mustang. The roof of the Lomanthang Monastery in the medieval walled city of Lomanthang was on the verge of collapse and Sanday’s job was to repair it. Three carpenters were brought in from Kathmandu and asked to train a group of local carpenters. Restoration of the wall paintings was done with the assistance of two Italian artists who were also asked to train locals on the craft.

John Sanday is currently involved with the Cultural Restoration Tourism Project (CRTP), a non profit organization that works with local communities to restore culturally important structures and promotes responsible tourism through ‘volunteer vacations’. “We are currently helping to rebuild a 300 year-old Buddhist monastery in Chairro (between Marpha and Tukuche) in Mustang,” he says. Sanday has also recently completed the restoration of a monastery in the Bunthang District of Bhutan. He informs, “We trained people on the use of modern technology and our emphasis was on ‘conservation and repair’. We have made a documentary of this project.” The architect joined Global Heritage Fund (GHF) in 2007 as its Field Director in Asia and Pacific. He has, in collaboration with the Cambodian government, set up a major conservation and training program at the 12th century Buddhist monastic complex known as Banteay Chhmar (The Citadel of the Cats) in northern Cambodia. He discloses, “Here too, we are imparting training on the use of latest technological advancements to assist in conservation efforts”.

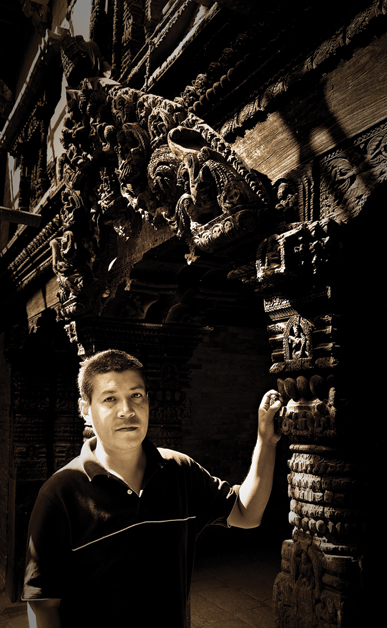

Dr. Rohit Ranjitkar

In an interview in 2007, Sanday noted that hundreds of historical buildings in Nepal needed to be restored; and that, even if some work was already being done, more conservation efforts were called for in Kathmandu Durbar Square and its surroundings. In 2000, the Kathmandu Durbar Initiative, a comprehensive plan to restore the temples at the site, was begun under the patronage of the U.S. Ambassador’s Fund for Cultural Preservation. Managed by the Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust (KVPT), the three major works included restoration of the Kal Bhairav Shrine, the Kageshwar Mahadev Temple and the Lakshmi Narayan Temple. The Kageshwar Mahadev Temple project entailed renovation of the timbers, the roofs and the walls as well as reconstruction of mud mortar on the walls in addition to further structural strengthening of the edifice. As for the Laxmi Narayan Temple, which was destroyed in the 1934 earthquake and rebuilt in an unoriginal style, photographic records were consulted to reconstruct it in its original form. And in the case of the 800-year-old Kal Bhairav Shrine, the concrete and marble walls made in the 1980s were completely removed and brickwork that had been used to repair damage caused by the 1934 earthquake was replaced with more authentic stone. Here too, photographic evidence was consulted.

The above three are but some of the scores of noteworthy projects completed by KVPT, an organization that is at the forefront of restoration activities in the country. Its Nepal Program Director is Architect Dr Rohit Ranjitkar, son of Sanday’s associate, Engineer Hari Bhakta Ranjitkar. Established in 1990, KVPT has its headquarters in New York and is said to be the only international non-government agency registered in the field of cultural heritage in Nepal. Architect Eduard F. Sekler, Professor at Harvard University, is one of the co-founders and is currently an honorary Chairman Emeritus and Chief Technical Director of the Trust. The other co-founder is Architect Erich G. Theophile who started his practice in Nepal in 1987 and is today one of KVPT’s Executive Directors.

Dr Ranjitkar and Architect Theophile were the consultant architects in many projects including Fishtail Hotel in Pokhara and two resorts at Namobuddha, 12 kilometres from Dhulikhel. Over the years, the Trust has restored scores of historically significant monuments, mostly in and around the world heritage sites like the Durbar Squares of Kathmandu and Patan. The list is long, including: Gokarna Parvati Temple (Gokarna-1990); Chupin Ghat (Bhaktapur-1996); Sulima Ratnesvara Temple (1998) and Patukva Agamche (1997), both in Patan; Uma Maheswar Temple (1992), Radha Krishna Temple (1994), Mani Gufa Temple (1992), Kwalkhu Pati (1992), Kulima Narayan Temple (1998) Tumbaha Narayan Temple (2000) and Ayuguthi Sattal (2001), all in Patan Durbar Square; and Chobar Ganesh(1998), Indrapur Temple (2002), Yetkha Bahal(2002) and Itum Baha (2005) in Kathmandu; as well as Narayan Temple (2003) and Jagannath Temple (2006) in Kathmandu Durbar Square. The 11th century Yetkha Bahal and the 13th century Itum Baha are included on the 2003 World Monuments Watch.

The Ayuguthi Sattal site in Patan was awarded the UNESCO Asia-Pacific Heritage Award of Merit in 2005. Excerpts from the citation read: “The restoration allows for an authentic physical reading of the square which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site... sustains the historic continuity of the space by reinterpreting its historic function as a public rest house through its modern use as an information and visitor’s center... the heroic effort of the partners allowed for authentic reconstruction using outstanding local artisans and materials based on meticulous documentation of the building... the first project to be catalyzed by private investment, and also (as) the first building to be placed under legal monument protection.”

Besides repair and restoration, KVPT has also initiated training, research and public advocacy programs. The Trust’s own headquarters in Patan Durbar Square is an example to others of how old houses can be restored for modern use without destroying their essentially traditional characteristics. Dr Ranjitkar and KVPT have their hands full today with many ongoing projects and many more in the planning stage. Currently, the Trust’s energies are focused on the Patan Royal Palace Campaign which includes restoration of the Sundari Chowk, the Mul Chowk and the Bhandarkhal Archaeological Garden at the palace complex. Future projects include more restoration works in and around the palace in Patan Durbar Square, such as the court building, the palace north wing, the 17th century Bhaideval and Visvanath Temples and the 16th century Narasimha Temple. Works planned in the Kathmandu Durbar Square include the 17th century Bansagopal Temple and Gorakhkali Shrine, the 18th century Saraswati Pati and the Drum House.

Professor Gotz Hagemuller

Without doubt, Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust is an organization that commands respect for its worthy efforts. It has a dedicated man at the helm in Nepal and he in turn, has a capable team working with him. As importantly, the Trust has strong backing, both nationally and internationally. There are, however, some others who are on more of a one man mission. Architect and conservation consultant Professor Gotz Hagemuller (Dipl. Ing.) is one such individual. He is the author of the 144 page tome Patan Museum: The Transformation of a Royal Palace in Nepal, in which he documents his restoration work at the Patan Museum in Lalitpur. More recently, he has been in the limelight for his restoration of the Gardens of Dreams in Keshar Mahal, Thamel. He has lived for nearly 30 years in Nepal and the Professor (an honorary title conferred by the Austrian President) is not associated with any particular firm working on heritage conservation. However, many reputed restorers and architects in the country are not averse to admitting that they have learned a lot working under his tutelage. The professor’s experience encompasses various architectural works in Salzburg, Stockholm, Vienna, West Africa, Bangkok, Rome, India, the Republic of Chad, and of course, Nepal. As a TV and radio producer, he has done documentaries on matters related to Nigeria, Latin America, Austria, Cambodia, Mali, Mecca, Nepal and India.

His association with Nepal began when he was appointed the Project Manager of the Urban Renewal and Development Project in Bhaktapur from 1979 to 1983. He says, “Bhaktapur is one of the best administered cities today and there is great emphasis on heritage preservation. It was the first city to impose entry fees and also the first to ban traffic of heavy vehicles.” Hagemuller believes that the success of the Bhaktapur project was primarily due to generation of employment for a large number of people as well as due to the formation of a community development committee through which locals were motivated towards social upliftment. He further adds, “The project also succeeded in reestablishing Bhaktapur, and more people are returning to the old city now.”

From 1987 to 1990 Hagemuller was responsible for the reconstruction of the 17th century Cyasilin Mandap (The Pavilion of Eight Corners) in Bhaktapur that was destroyed in the 1934 earthquake. He was then appointed the Consultant to the Department of Archaeology for implementation of the Conservation Master Plan for Swayambunath. In between, in 1991, 1992 and 1996, he undertook some important projects in Laos and Angkor in Cambodia. From 1991 to 1994 he was the Consultant of the Patan Conservation and Development Program. In 1993, he became a Member/Consultant of UNESCO/ICOMOS Monitoring Mission on Kathmandu World Heritage Site and from 1993 to 1996, was involved in the restoration and earthquake-reinforcement project proposal for the historic Palace of 55 Windows in Bhaktapur. It was during the period 1986 to 1997, as Chief Architect and Project Coordinator of the Patan Durbar Conservation and Museum Project, that Professor Hagemuller reached his professional zenith. The restoration of the 17th century Patan Palace and its conversion to adaptive modern use led to the formation of the famous Patan Museum – a self sustaining cultural institution and a revenue generating prime tourist attraction of international standards. The period 2001 to 2007 saw the professor immersed in the restoration of the Keshar Mahal Garden of Dreams, another equally monumental task.

One of his recently completed projects has been the restoration and rebuilding of an old defense structure in Trongsa in Central Bhutan. The Ta Dzong, a cylindrical stone watchtower rising five storeys, was built in 1652. It has been resurrected into a museum blending tradition and modernity. Eleven galleries sit at split-levels over five floors to a rooftop that functions as a viewing gallery. According to his long time associate Thomas Schrom, “We also restored two temples within the complex.” Professor Hagemuller’s graduate and postgraduate education includes Architecture from the Technical University in Vienna in 1966, Film and Television at the Academy of Fine Arts (Vienna) in 1962, and studies in Urban Development Planning at the London University in 1972. He has held many important posts in his career including Regional Housing Expert for the UN (FAO) in Bangkok and Rome, consultant for UNIDO/UNDP in the Republic of Chad, board member of IG Spittelberg and board member of the Austrian Architects Association. In 1977 he was awarded the second prize in an international competition for the new National Reza Shah Pahlavi Library in Teheran. His other achievements include TV and radio documentaries such as ones on the Yoruba Shrines of Oshogbo in Nigeria (1968), Austrian Aid in Latin America (1973), on the state of the Austrian Public Health System, entitled ‘Krank’, in 1974, and another called ‘Gehorsam’ (1975). In 1976, Hagemuller made a movie-film called ‘Kanga Mussa’. Hagemuller was the Chairman of the Austrian Filmmakers Syndicate from 1977 to 1978.

Rabindra Puri

Another well known restorer who prefers to go it alone is Rabindra Puri. He lives in Dattatreya Square of Bhaktapur, near to his magnum opus in the field of restoration, the ‘Namuna Ghar’, a feat that won an Honorable Mention in the 2004 UNESCO Asia Pacific Cultural Heritage Conservation Award list. Originally a ramshackle and dilapidated poultry farm, believed to be around 150 years old, Puri’s enthusiastic efforts resulted in its conversion to a three-storied house in the traditional architectural style of Bhaktapur. Says Puri, “Namuna Ghar has been restored keeping the traditional Newari design intact and it was made possible by a year and a half of dedicated labor.”

The innovation that went into the remaking of Namuna Ghar must be appreciated. The ground floor has an impressively designed bathroom with burnished copper and bronze fittings that speaks well of Puri’s innate creativity. The first floor has a lounge, a library and a bedroom, while the second floor also has a similar lounge, a bedroom and an office along with a becoming veranda. On the top floor is a kitchen-cum-dining room and a comfortable lounge off of which there is a small alcove balcony. Indeed, the Namuna Ghar is something of which Rabindra Puri is proud, and one can surmise that its success must have driven him still further in the field of restoration. He has renovated and restored a number of other houses including a guest house in Bhaktapur and a residential building in Kathmandu.

For the past few years he has been immersed in restoring some private properties in Panauti. Puri says, “I have finished restoration of five houses of which two have already been rented out. Actually, I am very interested in restoring this historical town to its old grandeur through its beautiful traditional architecture.” He is also busy with two ambitious restoration projects funded by Spanish investors involving scores of houses around Gacchen Tole and Nagpokhari, both in Bhaktapur. One of them is the ‘Tony Hagen House’, a house that the famous geologist/writer mentioned in his book on Nepal as the first concrete building he came across in Bhaktapur. Puri has completed its restoration very recently into a traditional Newari residence and dedicated it to Hagen. I Sanga, Puri is starting a housing colony of traditional houses called Arte Namuna Housing, again with the same Spanish collaboration. He also informs, “I am also on a personal mission to build at least one community school every year. The first one was finished last year in Fulbari of Kavre district.” Rabindra Puri is on the fast track having completed about 34 projects to date, including a Shivalaya Temple in Sankhu, and says with deserved pride, “I have 90 workers (woodcarvers, wood carvers, metal smiths, bricklayers, etc.) involved with my projects. Now I am planning to add 50 more.”

He is, doubtless, contributing substantially to the upholding of traditional skills and architecture in the country. And, yes, he is the right man to do so. After all, he himself is a sculptor who likes to work in metal; he teaches the craft at the Kathmandu University Department of Art and Design. And that’s not all. He has Bachelor’s degrees in Arts, Commerce, Law and Fine Arts as well as a Master’s degree in Development Policy from Bremen University in Germany. Nevertheless he considers himself first and foremost “A restorer and renovator of traditional ho uses.”

Dwarika Das Shrestha

“Dwarika’s has become an asylum and hospital for the care of wounded masterpieces in wood, where they are restored to their original beauty, a school for training and practice of traditional arts and skills, a laboratory to research old techniques, and a living museum where people may enjoy and understand this heritage which is not only Nepali but, that of the human race – Dwarika Das Shrestha (1925-1992)”. So reads a plaque at the Dwarika’s Hotel in Gaushala, Kathmandu.

Dwarika’s Hotel has demonstrated that a proper blending of cultural restoration and tourism leads to the preservation of historical artifacts otherwise endangered by commercialism. It was in 1952, that the late Dwarika Das Shrestha realized that the rich architectural heritage of the Kathmandu valley was in acute danger. As the story goes, he was out jogging one morning when he saw some carpenters sawing off the carved portion of an intricately engraved wooden pillar, part of an old torn down building. He also saw amidst the rubble, pieces of ancient carved woodwork that, to his dismay, he found were about to be carted off as firewood. He could not control himself and impulsively arranged for the carpenters to receive new lumber that they required in exchange for the old ruined carved pillar.

From then on, every time he heard about an ancient building that was going to be torn down, he would go and buy as much of the ancient wood carvings as he could. His growing collection beget the problem of storage of the bulky material. This led to his decision to construct a building in the traditional Newari style using the rescued carved doors and windows. This building became one of several buildings of Dwarika’s Village Hotel at Battisputali, on the east side of Kathmandu. This heritage hotel won the PATA Heritage Award in 1980.

Professor Sudarshan Tiwari

Professor Sudarshan Tiwari is the author of Tiered Temples of Nepal (1989), Ancient Settlements of the Kathmandu Valley (2001), and the famous The Brick and the Bull: An Account of Handigaun, the Ancient Capital of Nepal (2002). He is an exceptionally erudite and knowledgeable teacher who is adept on the subjects of traditional architecture, history and heritage. He once worked as a consultant for the Department of Archaeology and was part of the Maya Devi Temple and the 55 Window Palace Conservation Projects in Lumbini and Kathmandu respectively. He has certain unique views on the subject of conservation. He confesses to advising organizations like UNESCO to use a different approach towards preservation activities in Nepal. He has said in an interview in an architectural magazine, “Many of the traditional heritage sites are ‘season-related’ and most of them are focal points during festivals which are almost all seasonal in occurrence. So it would not be a good idea to approach restoration and other activities from a purely ‘historical-year’ angle.”

In the same interview, answering a question as to how monument zones once managed to get themselves into the ‘Endangered List’, he said, “One reason could be that we tried to include too wide an area when zoning heritage sites. Long time residents living within the zones cannot be expected to adhere to standards which will keep them apace from modern development.” But he has also conceded, “However, since the surrounding environment is vital when talking about heritage sites, perhaps it is also right that a wider area has been considered. Still, if so, we have to explore the causes of failure. Is it that the by laws are not being followed? Or is it that the by laws are unpractical? Is it that the laws are good from a western point of view but not so from the poor residents’ perspective?” The professor also prophesized, “A time could come when conservation activities in South Asia will be handled by Nepalese architects. We have garnered so much valuable experience.”

Kathmandu Valley – A Restorer’s Paradise

Well, one does look forward to Professor Tiwari’s prophesy coming true. There are seven World Heritage Sites in the valley alone and certainly, it’s a relatively high concentration of such important landmarks in one place. This too has contributed towards increasing the enthusiasm for restoration, as it is rightly believed that Kathmandu’s ancient heritage and culture have played a big part in promoting tourism, the nation’s major economy. And of course, where else can heritage be more evident than in the magnificent architecture of the valley?

And there can be no better way to validate this point than by quoting from Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust’s website: “The Kathmandu Valley boasts a concentration of monuments and townscapes of an importance almost unmatched in the world. The unique syncretism of Hindu and Buddhist cultures which gave rise to these monuments survives today in Nepal making their protection, repair and maintenance as ‘living monuments’ all the more compelling. Despite a number of local and bilateral conservation projects, the volume of monuments at risk far exceeds the available manpower and funds. Not only are a number of buildings in several World Heritage Sites awaiting urgently needed restoration, but in addition, every year throughout the Kathmandu Valley significant monuments such as monasteries, temples, and historic houses are lost. The provision of relatively modest funding could save them.”

Reinhold Messner

“Traditional mountaineering is the art of not dying.” Reinhold Messner is one of the most well known...