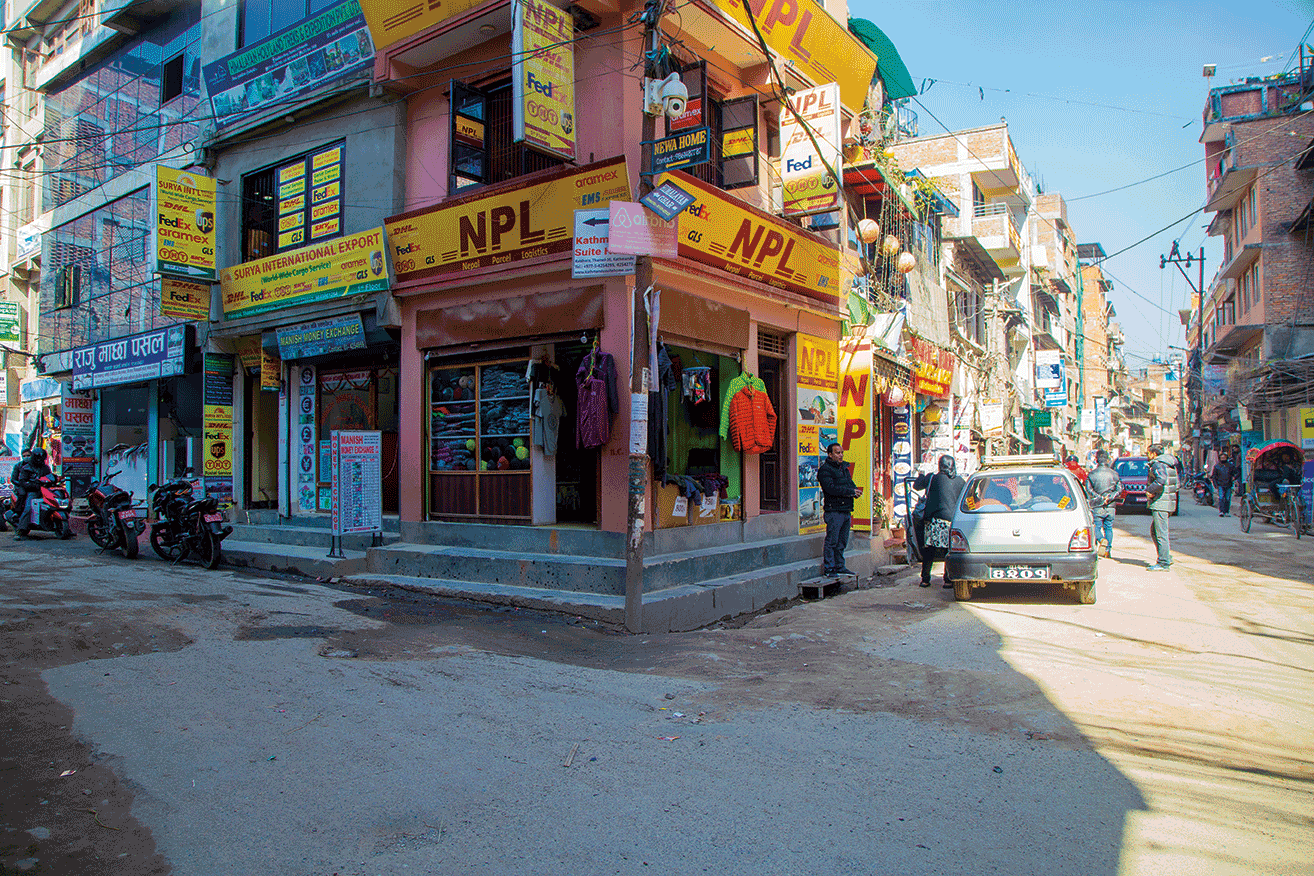

Text by: Tan Pei Lin Photo: Saurav Dhakal

Nepal is a popular location among tourists simply for being home to the mighty Himalayas; a large portion of the tourism industry relying heavily on natural conditions and resources. With the Earth dealing with changes in climate, it is inevitable for the condition of the mountains to be in tandem with Mother Nature’s moods.

Home to the world’s largest mountain and vast Himalayan regions; Nepal is heavily dependent on mountain and nature tourism as its source of income. The close-knit relationship between the climate and tourism is standing the test of time as the issue of global warming looms dangerously, threatening to affect nature’s wonders.

“A changing climate leads to changes in the frequency, intensity, spatial extent, duration, and timing of extreme weather and climate events, and can result in unprecedented extreme weather and climate events,” quoted from a paper written by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

The changes in the climate will unleash an onslaught of extreme events that will affect not only the people in the mountains, but the tourism industry as a whole. This will not just be confined to the mountains – even popular tourist places like Pokhara and Chitwan National Park will not be spared from these climate-induced events.

CHANGING MOUNTAINS

CHANGING MOUNTAINS

Global warming is a slow process with gradual effects, but Nepal’s mountain tourism is bearing the brunt of it now. Not just glacier lake outbursts, but also erratic weather patterns, decline in snowfall and increase in temperatures. Mountain tourism in other countries (e.g. Swiss Alps)requires regular snowfall to sustain their market of mountain sports. However here in Nepal, people come to the Himalayas for the adventure that she offers –the difficult terrains, beautiful nature and cultural experience; and also because Mount Everest is the highest mountain in the world and will always be even without snow-capped peaks.

With over thousands of villages and settlements in the folds of the Himalayas, these untouched places might be affected by climate changes in the region. As pit stops for trekkers, these villages are home to teahouses, lodges and guesthouses that serve as a source of income for the local people. Floods can destroy these structures, and their houses and even endanger their lives. Glacial lake outbursts are just the tip of the iceberg. The increasing of temperatures can possibly lead to the quicker melting of snow and the decrease of snowfall, and more torrential rain.

People on the mountains are aware of changes happening; when spices strive in seasons that they aren’t supposed to and even when storage methods for their crops not working as well as it did before. These odd events may seem as trivial, but it may be an indicator to the people that the weather is changing.

Above 2700m above sea level lies a small village, Najingdingma, where the local people practice a unique culture of storing their potatoes in the snow covered ground for at least six months, recounted Mr Saurav Dhakal. He recently returned from the Great Himalayan Trail (GHT) as part of the Climate Smart Celebrity Trek. He also collected stories from the local people to be a part of Story Cycle, an online platform where stories are shared.

In the next season after six months, the potatoes are then dug out and eaten. “The interesting thing is that now, nobody knows why it is not working perfectly. In the past, it tasted perfect. I think it is due to the layer of snow which used to stay for six months, but now it only remains for three to four months,” said Mr Dhakal.

FLOODGATES

FLOODGATES

The formation of glacial lakes are seen as a natural part of Mother Nature’s work, but the increasing rate of the number of lakes is alarming. Nepal’s glaciers are seen to be thinning and retreating, resulting in the formation of small and large glacier lakes. Regardless of size, these lakes pose as a dangerous threat to those residing below these glaciers.

The dams that hold the growing lakes are made of young and loose debris that consists of sand, stones and boulders. Called “moraine”, these walls are not exactly the sturdiest structures around. Vulnerable to extreme water pressure, large waves and even earthquakes, the breaking of the dams will result in flooding downstream. This phenomenon is known as glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs).

In 1985, a glacier lake Dig Tsho burst in its natural dam after an ice avalanche hit it. It had caused massive damage – considering how it had destroyed the almost complete Namche Small hydropower plant (estimated cost of 1.2 million USD), bridges and also claimed many lives. In order to prevent another disaster, a mitigation project to initiate an early warming system in one of the more potentially dangerous lakes, Imja Tsho, had just recently begun.

“The lakes should be monitored very closely; mitigation and early-warning systems should be implemented. It’s not just big lakes that are dangerous,” said Mr Pradeep Mool, a GLOF and remote sensing specialist, citing the example of how the bursting of a small lake Tam Pokhari had caused measurable damage.

However the bursting of Glacial Lakes and amount of snowfallin the mountains are not the only problem in the conversation of climate change. Even in cities like Pokhara had experienced devastating floods in May 2012 that had swept away villages, markets and lives.

With many vulnerable settlements on the borders of Pokhara, the tourism industry in the city is yet to be largely affected. In a BBC article, Professor Krishna KC the head of Geography at Prithivi Narayan Campus said that the settlements are at risk, but he felt that the main tourist center in Pokhara is not facing an immediate threat due to its distance from the waterways.

Even places like Chitwan National Park is not spared from nature’s wrath. With the Rapti River flowing through the national park, the place is in danger from flooding. In 1990, due to an infrastructural failure in the dam on the Rapti River had burst resulting in a flood that had swept away 26 people and 880 houses.

These isolated events do not inspire much change in environmental policies or even talk of any eco-friendly infrastructure yet. “It comes into the news for awhile but it doesn’t shake the industry,” said Mr Kashish Das Shrestha, a self-funded researcher and journalist who writes about environmental issues in Nepal.

He added that the industry really needs to acknowledge the fact that there are climate-induced events occurring, and it will affect the industry in the long run. “This is just not the conversation that they (the tourism industry) are having right now.”

DARK DAYS

Climate-induced events can possibly be more localized than more people realize. Besides the usual culprit of greenhouse gases and carbon footprints, the presence of black carbon is now identified as source of trouble for the climate. In fact, the carbon footprint in Nepal is calculated as less than 0.1 tonne per person per year. As compared to other countries like the United States and Singapore, which are 40 and 50 respectively, it is comparatively low.

The burning of firewood is a common occurrence in Nepal – in the cities and in the mountains. In the cities it is more prevalent in winter when the nights are longer and colder, combined with the onset of loadshedding.

Black carbon is the black parts of smoke that are formed by incomplete combustion of fires. Once black carbon is released into the atmosphere, it absorbs sunlight, resulting in two effects. Firstly, the atmosphere begins warming up with the presence of black carbon and secondly it reduces the amount of sunlight reaching the earth. While not completely discounting the consequences of greenhouse gases, black carbon is said to be contributing to the addition melting on the Himalayas. Even visually, the black particles in the air also contribute to poor visibility.

“When I was a kid I could see all the mountains everywhere from Kathmandu, but now you can’t really because of the poor visibility. Even the mountain flightsare delayed by the haze,” said Mr Mool, who is also the Programme Coordinator of the Cryosphere initiative.

The main question that the tourism industry should be asking is, how can they make the entire experience in the mountains less energy intensive, without straining it’s resources? Mountain tourism in Nepal has been ongoing since the 1960s, and has been done the same way ever since. What people don’t notice is that over the years, the mountains are slowly changing and are responding to the effects of people being on the mountains.

“The way the industry has been doing mountaineering is not changing, and the quantity of people on the mountains are growing. It’s taking a complete toll on the mountains,” explained Mr Shrestha.

NO FRESH WATER

In the current Climate+ change exhibition at Nepal Art Council organized by ICIMOD and GlacierWorks, there has been evidence compiled together to urge the public about how current and relevant these changes in the environment are.

With projected evidence, the temperatures in Langtang Valley are said to increase by an estimated 6 degrees Celsius within a hundred years.This warming of the Langtang glaciers could very much affect the amount of snowfall and glacier melt. Working in a snowball effect, the amount of snowfall also affects the amount of fresh water available for residents of the Himalayas.

According to Climate Change Specialist Dr Arun Bhakta Shrestha, the higher the altitude, the more significant the impact of increasing temperatures will be.

More villages in the high altitudes are turning to tourism as an alternative source of income. They depend largely on snow and ice as their source of fresh ground water, which is essential for their livelihoods and to sustain lodges and teahouses that are made for tourists.

“Those near the snow-covered areas will experience a more significant impact, because their s ource of water comes directly from glacier melt or snow melt,” explained Dr Shrestha.

For people living high up in the Himalayas, fresh water is extremely important because it is one of the main sources of water. With the main source of water threatened, there would be a lack of fresh water to drink and also to sustain these tourism spots. In subtle ways, climate changes in the mountains will take a toll on its closely related partner – mountain tourism.

One such example is the village of Samzong, with population of 80 people that is located in a remote area of the Upper Mustang. Due to the drying up of the nearby rivers, water scarcity is a very real issue for them. Being forced to relocate to a different land, their movement can result in a loss of culture along the trails. What lays behind are bare abandoned fields and houses which used to be agriculture fields and homes.

Another example of how the mountainous people managed to adapt to the onset of climate changes is the village of Yara. The lack of fresh water is affecting the production of their crops, which is also their source of income. Instead of relocating, the community decided to utilize tourism to manage their income. Nearby Yara lies a site which is frequented by pilgrims – by offering shelter and transportation, the people managed to cut back their losses from the lack of crops.

ERRATIC WEATHER

When good weather turns bad, business also takes a turn for the worst. Erratic and unpredictable weather is detrimental for popular tourist villages – which most often than not serve as tourist pit stops. When unpredictable and bad weather strikes, flights to these places high up in the mountains will be delayed and cancelled, affecting the growth of tourism.

The main issue about how these climate changes in the mountains affects the tourism sector is the safety of the tourists, explained Dr Shrestha. “Because of the melting glaciers, it might have affected the mountaineering routes resulting in challenges and decreased accessibility.”

It’s not just now that erratic weather has hit the Himalayan region. Back in November 2011, there was a major flight cancellation that had lasted for a week due to poor weather conditions in the Everest region. This had major repercussions on Nepal’s tourism and also tourists who had their schedules disrupted. People could have lost their jobs due to this weeklong delay. In the past, three to four days of delay is normal, but nowadays when the one to two week delays are deemed as normal, the industry should start being concerned. According to the official statistics of the Nepal Tourism Board, the average length of stay for tourists in Nepal is about 12 – 13 days.

“I think in this day and age in global tourism, it is impossible to demand more than two weeks for one travel destination,” said Mr Shrestha. The unpredictable delays in the mountainous regions will behave as a major factor in the tourism industry.

DOWN BELOW

Climate changes in the mountains doesn’t just affect the people in the Himalayas, the people down below that form the foundation of mountain tourism will also bear the brunt. Trekking companies, flight companies and equipment companies might not see visible impact on sales, but in the long run strategies may have to be altered to deal with it.

The fact is that this is a topic that is not on the top of anyone’s minds now – lest most of the tourism industry. With the main issue being the lack of proper information flow, people in the tourism industry are not fully aware of the repercussions.

“It’s the same mountain with either less snow this season or more snow next season. Besides the glacial lakes and reports on the Everest region, I don’t see what other major issues there are,” said Mr Namgyal Sherpa, director of Thamserku, one of the largest trekking companies in Nepal.

Nonetheless, baby steps are being taken in the right direction. In an innovation spin to promote green behavior and also remain sustainable at the same time, Yeti Airlines is working together with local partners in a tree plantation program. For every flyer on the airlines to specific western regions of Nepal, some money will be set aside to be used as funds for the planting of trees. So far, 58,000 trees have been planted so far, meeting almost half the target of 100,000.

THINKING SMART

Trails like the Great Himalayan Trail (GHT) are currently being promoted as eco-tourism trails because the trail is largely untouched by developments and construction.

“There is nothing, so it is all natural. There are no structures, the people’s methods are all natural and organic,” recalled Mr Dhakal, from his experiences on the GHT. The methods practiced by the local people are traditional and ancient. With little technology for support, generations of these people find their own ways in dealing with the changing climate. Using energy from the sun, hydropower and water mills, these age-old methods prove to be sustainable enough.

As the British Council Climate Champion, he has been focusing on the adaptation methods of people who live in the mountainous regions, and he believes that their traditional methods can be enhanced with technology to make it more feasible to apply to the masses. The point, he emphasized, is not to resist incoming developments, but to make sure that these developments are “climate resilient”.

“If you want to build a bridge, build a high one, not a low one,” explained Mr Dhakal, citing an example of how new infrastructures must take into consideration the changing climate, in this case, floods.

WHAT LIES AHEAD

Climate change is not necessarily detrimental to the tourism industry, argues Mr Dhakal. It all depends on how you look at it. By changing the marketing approach, the industry doesn’t have to suffer because of climate changes. But in order for changes to occur, the industry first has to acknowledge that changes are happening. These climate-induced changes will happen – sooner or later, and they cannot be ignored.

Nepal is still in a phase where she can make drastic changes because she is still in that transition phase, reasoned Mr Shrestha. “In fact this phase it extremely critical to decide how we move ahead. For Nepal, it’s not too late because we are not developed, we are a developing country.”

For now, the industry is still very focused on season-to-season profits, which is as good as looking through rose-tinted glasses. This shortsighted view needs to be changed as the landscape is changing. This slow but certain change in Nepal’s landscape doesn’t just affect the mountains and its people. People in the cities will also bear the brunt of these effects.

Already in China, travel advisories have been issued warning travellers about the smog and bad air quality in Beijing. There have been reports that tourism in China had dipped due to these travel advisories.

Nepal hasn’t reached that stage yet. Let’s face it, Nepal’s tourism is extravagantly reliant on nature and it’s resources. It only makes sense to shift and create policies that are advantageous towards the environment, in order to maintain the high standard of tourism in Nepal.

As Mr Shrestha articulates: “Nepal’s approach should be: as much as she can, the best she can. Even if the world falls apart, she should be prepared in its capacity.”

Our changing rooftop

Text: Kapil Bisht

The roof of the world is changing, and directly affected are the Nepalis living immediately beneath – from those inhabiting the mountainsides to those residing in Kathmandu Valley and beyond.

As climate change impacts the Hindu Kush Himalayan region, people need to tackle the issues it raises. Climate+Change, an exhibition held at the Nepal Art Council, aims to do just that by educating people on the changes in the region and providing a platform for dialogue.

The exhibition, organized by the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) and GlacierWorks, spans three floors. The first explains how urban areas like the Kathmandu Valley are aggravating, affected by and addressing the effects of climate change. The middle floor discusses how various transboundary landscapes have been transformed, with case studies of how villages have adapted. The final floor is dedicated to the Everest transboundary landscape as a case study of change.

Events such as talks and movie screenings, to engage visitors into discussing the issues at hand, take place regularly at the exhibit. A complete calendar can be found on the Climate+Change website. The exhibition remains open till 13 April 2014.

Top 3 Must-sees

Traverse the Everest landscape

The panoramas beside the staircase up to the balcony make you feel like you’re climbing Everest itself. At the top, though, you can explore the Everest landscape in incredible detail with just your fingertips. In a collaboration with Microsoft, GlacierWorks’ images from their flights around the Everest landscape have been stitched together by a program called Photosynth to create the illusion of an actual flight video. The screen also allows you to direct the path, to some extent, and zoom into images to view Everest and its surroundings in stunning detail.

Pieces of pollution

Showcased in the corner of the first floor is the exhibition, The Truth of A Sacred River. The Bagmati is considered a holy river and the source of Nepalese civilization. Yet, its passage through the Kathmandu Valley has led to it being polluted terribly. A group of artists traced the Bagmati to the edge of the Kathmandu Valley and collected objects found in the water, casting them in individual transparent cubes that have been hung in display. The objects found reflect the lifestyle of the city and highlights the attitude towards pollution.

Voices of the people As the stunning panoramas of the Everest landscape gaze down on you, people who live there tell their tales through a photo story. On the top floor, photographs of different people who live in the Everest transboundary landscape relate how things have changed for them. A particular point of contention is the glacier lake Imja — if it bursts, lives will be destroyed. It is a fascinating multi-faceted story, told in their own words in both English and Nepali.

A day of wet roofs

Text: Kapil Bisht

“The rain didn’t let up…Due to our slow pace and the relentless rain we decided to end the day’s walk.” Simple lines from my journal, made memorable solely by the word “rain” in it. That particular rain came on a morning in May 2012, during a trek in the Mustang district. Combining with the notoriously punctual Mustang winds, the rain turned a pleasant day into a wretched one; gloom descended into the valley, the mountains disappeared, and we began to get wet.

Rain in the rain shadow region of Mustang, and the subsequent efforts to keep oneself dry, is as anti-climactic as it can get. But aberrant weather had almost become a theme on that trek. Two days ago, we had been welcomed at our camp site in the mountains with snow. It was May; we weren’t expecting it. The local shepherds near whose tent we had pitched ours told us it wasn’t unheard of to have snow in May, but confessed that weather patterns were certainly changing. A few days before that, while paying a visit to the local conservation officer in Jomsom, we had walked into a talk program on climate change. After the program, my companion interviewed the participants about yarsagumba. The locals lamented the decline in yarsagumba yield, blaming climate change.

I, a first-timer in Mustang and a visitor still harboring hopes of seeing the place as it was described in books like Michel Peissel’s Mustang: A Lost Tibetan Kingdom, was unprepared for change. My hopes were dealt a big blow in Jomsom, where there were ATMs and bakeries, more motorcycles and taxis than yaks. Change had already taken place in Mustang—years ago. I accepted it reluctantly.

But there was no overlooking climate change in Mustang. I had watched a slideshow during that talk program of retreating glaciers and glacial lakes threatening to burst. I realized that climate change was as much a threat to the Mustang of my dreams as consumerism or roads. Threats to culture, I realized, came from climate change as well. I came to that realization only when I began to write this piece. On that uncharacteristically soggy day in Mustang, looking out the dining room window of our lodge, I had seen its mud roof turn slimy. What will happen to the tradition of having mud roofs if rains become more frequent in Mustang, I now wonder? Will the locals opt for concrete roofs? Trekkers can cope with such a change by carrying a raincoat, but how, I wonder, will a rain shadow region cope with rain.