Shiva (Shyam) Sunder Maharjan, 78-year old resident of Pyangaun of Chapagaun Village Develop-ment Committee (8 kilometers south of the ancient city of Patan) has only one worry: there is no one to carry on his century-old craft of making beautiful bamboo buckets used to measure grains. With Shyam Sunder and his colleagues in an advanced phase of their lives, their venerable skill is on the verge of extinction.

Since few boys and girls of the new generation know about the tradition of bamboo crafts, their elders are very much concerned about maintaining the unique identity of the village. Moreover, few villagers see economic prospects in upholding the tradition. As a result, the Kathmandu valley stands on the brink of losing another component of its vibrant cultural tradition.

Since few boys and girls of the new generation know about the tradition of bamboo crafts, their elders are very much concerned about maintaining the unique identity of the village. Moreover, few villagers see economic prospects in upholding the tradition. As a result, the Kathmandu valley stands on the brink of losing another component of its vibrant cultural tradition.

That danger has alarmed many. “Kathmandu valley is full of heritage. No one can (learn) it in one lifetime,” says renowned archeologist Dr. Safalya Amatya. “Villages like Khokana,

Sunakothi, Bode, Thimi, Pyangaun, Nakdesh and Thaiba each require a lifetime’s study. All these villages have their own identity with numerous monuments and temples,” Dr. Amatya says. “Unfortunately, we have hardly made any effort to preserve and protect our heritage.”

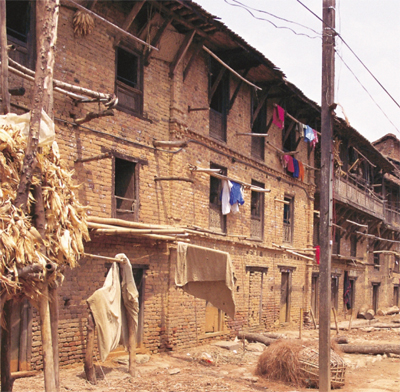

Apart from the main historical cities of Kathmandu valley, many other culturally important cities are burying their culture and local identity under the superstructure of modernity. The process of change has hit the tradition of making bamboo buckets, but modernization is yet to permeate the living patterns, social formation and social hierarchy of Pyangaun. Although linked directly with the capital city by modern modes of transport, the villagers still live the way they did centuries ago.

Isolated from the outside community, the process of transformation in the village has been virtually invisible. From birth to marriage, the villagers have not needed the support of outsiders. The strong social bonds are rooted in the sturdiness of community support, which has helped Pyangaun maintain its own cultural identity.

A large dirty water pond at the entrance to the village, it’s narrow alley and old houses are reminders of the past. From language to rituals, Pyangaun is remarkably different than the other Newar villages in the adjoining areas. Villagers like Shyam Sunder see no need to change themselves.

The elders are still thrilled while describing the craft to outsiders. “There was adventure in collecting the aged bamboos. The wider the width and the older the age (of the babmoo), the bigger the size of the bucket and the greater its life,” says Shyam Sunder. To collect the old bamboos, Shyam Sunder¹s colleagues had to cross the Bagmati to reach the trail of Chure in Makwanpur district in the south.

To prepare buckets of different sizes, first they cut the bamboo into pieces and use fire to flatten it into a mould. “We have our own techniques of making the bamboo measures. When I was young, we used to go up to Tin Mangale, Chayu Chayu and other villages of Makwanpur districts to bring wild and aged bamboos. The demand for bamboo buckets declined with the advent of plastic and chemical products, so it is useless to go for such a long trekking nowadays. I am still making weighing measures using the bamboo available nearby, but these products are not as strong as they used to be,” Shyam Sundar says.

Despite its potential, no one has tried to understand the importance of the skill. No Nepalese has ever come to recognize his work, although some tourists do. “A few years ago, some foreigners came to my home and bought some products,” says Maharjan.

“In the urban areas, our weighing tools were replaced by metal products. But they were widely used in rural areas until a decade ago. They are still (sometimes) used in the rural areas in and around Kathmandu to weigh grains,” he said.

Jetha Maharjan, 56, has no regrets about not learning the skill. “Since no one is coming to buy our products, what is the use of learning such old-fashioned skills?” he says. “Pun Bahadur, Shyam Sunder, Ram Sunder and Macha Maharjan are the few elders who possess the skills,” says Jetha. They are tiny drops in the river- a village of 250 households.

Shyam Sunder, grandfather of ten, living in his old house in Pyangaun with his wife, is very much worried about what might happen to his tradition after his death. Although he has seen many difficulties and hardships in life and has encountered many changes, the changes surrounding the decline of his craft hurt him the most. As the oldest man of the community, Shyam Sunder considers himself an unfortunate man with no one to pass on his skills.

The worries of elderly people like Shyam Sunder are understandable, as the skill of making bamboo buckets not only identifies their villages but also represents a unique heritage. Pyangaun played an important role in supplying traditional bamboo units to measure and weigh goods.

Until the modern weighing system was introduced, the buckets made in Pyangaun were legally recognized measures. “We have been given lalmohar (state authority) recognizing our bamboo measuring buckets as standard,” said Maharjan remembering the past.

Before the introduction of the modern metric measurement system, Nepalese used the traditional systems of mana, pathi and dharni. For weighing food grains, the mana-pathi were used. A mana is equivalent to about half kilo and a pathi is a bucket that measures up to four kilos of rice and three and a half liters of liquid.

Along with the weight measures, the villagers also make a variety of other items, including bamboo buckets to store foodgrains,oils, lamp-wicks, and other household necessities.

Unless there is some intervention in time, the tradition of making products from bamboo will soon vanish from Kathmandu valley. Much will depend on whether Shyam Sunder, Ram Sunder, and Macha Maharan can find people to carry on their tradition. Otherwise, the craft will join the list of Kathmandu Valley heritage that can only be found in history books.

Reinhold Messner

“Traditional mountaineering is the art of not dying.” Reinhold Messner is one of the most well known...