Resting places have been part of the Nepali culture in the hills and the terai; in Kathmandu Valley, they are artistically constructed with bricks, stones, and wood.

Traditional resting houses were very important architectural features of towns the countryside since ancient times in Nepal. Outside the valley in the hilly regions, chautaris, or elevated resting places under the shade of a pipal tree, is a common sight, so the same in the terai region. The ones we see scattered around Kathmandu Valley date since the medieval times. Although scholar Wolfgang Korn, the first foreign scholar to study traditional Newari architecture, mentions that the first reference of these resting places date back to the Licchavi period, we have no physical evidence of this, but know about them through numerous stone inscriptions.

Traditional resting houses were very important architectural features of towns the countryside since ancient times in Nepal. Outside the valley in the hilly regions, chautaris, or elevated resting places under the shade of a pipal tree, is a common sight, so the same in the terai region. The ones we see scattered around Kathmandu Valley date since the medieval times. Although scholar Wolfgang Korn, the first foreign scholar to study traditional Newari architecture, mentions that the first reference of these resting places date back to the Licchavi period, we have no physical evidence of this, but know about them through numerous stone inscriptions.

Broadly, all resting places were termed as dharmasalas, under which are many sub-categories, the phalcha being the Newari term of the pati. Traditionally, the phalcha is a raised covered platform that can be either free-standing, or attached to an existing building. The front façade of both types are colonnaded with widely spaced wooden posts. According to this feature, they are typologically differentiated into mandapa, or free-standing square phalchas with 16 pillars and three bays.

Broadly, all resting places were termed as dharmasalas, under which are many sub-categories, the phalcha being the Newari term of the pati. Traditionally, the phalcha is a raised covered platform that can be either free-standing, or attached to an existing building. The front façade of both types are colonnaded with widely spaced wooden posts. According to this feature, they are typologically differentiated into mandapa, or free-standing square phalchas with 16 pillars and three bays.

The other type is attached to another building, mostly of a single, or rarely two bays, and a rear wall. According to variety, rectangular ones are called taahaa phalchas, those that are angular or L-shaped are called kuu phalchas, those attached to houses are called lidha phalchas, and two of them attached together are known as joo phalchas. According to archeologist Sukra Sagar Shrestha, the inscription of a particular phalcha in Kirtipur mentions the construction of a Grihaalankara phalcha, one that is attached to an ordinary house to decorate and add value to the house. Beside these, there are others dedicated to different deities.

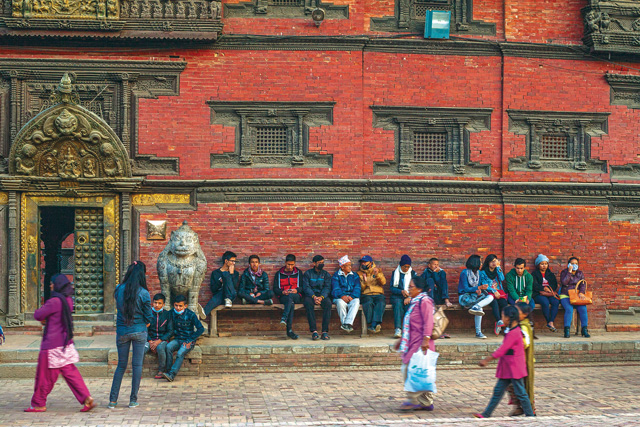

Phalchas have multiple functions, as a resting place for travelers, and a venue for social and religious gatherings. During different times of the day, the same phalcha serves the role as a space for children to play; for the elderly to chat and make cotton wicks to light butter or oil lamps; for old men to bask in the sun and keep pace with national and international events through newspapers; and sometimes, even a venue to play cards. The settlements of Patan, Kathmandu, and Bhaktapur are dotted with several hundreds of them, at the entrances, at crossroads, near ponds, streams, bridges, and especially near temples. By the mid 20th century, many of these spaces were transformed into shops, house clubs, and libraries. There are special phalchas reserved for the recitation of bhajans (religious hymns) performed daily, weekly, monthly, or annually. Musicians face the deities when reciting bhajans in phalchas near or attached to temples.

Phalchas have multiple functions, as a resting place for travelers, and a venue for social and religious gatherings. During different times of the day, the same phalcha serves the role as a space for children to play; for the elderly to chat and make cotton wicks to light butter or oil lamps; for old men to bask in the sun and keep pace with national and international events through newspapers; and sometimes, even a venue to play cards. The settlements of Patan, Kathmandu, and Bhaktapur are dotted with several hundreds of them, at the entrances, at crossroads, near ponds, streams, bridges, and especially near temples. By the mid 20th century, many of these spaces were transformed into shops, house clubs, and libraries. There are special phalchas reserved for the recitation of bhajans (religious hymns) performed daily, weekly, monthly, or annually. Musicians face the deities when reciting bhajans in phalchas near or attached to temples.

Phalchas have a special role during the Bisket Jatra in Bhaktapur; 34 deities leave their respective dyo-chens (god-houses) and are exhibited in phalchas. On the last day of the festival, devotees worship these deities by circumambulating the space. Such annual performances demonstrate the rebirth of the deities, and validate their protective power. These deities, when in their respective dyo-chens, are not accessible to the common man, thus during the festival time, one gets to see devotees in their thousands, thronging to make offerings and pay their due respect to the gods. In Patan, during the chariot procession of Matsyendranath and his companion Minnath, samaya (ritual food) is distributed from many phalchas en-route.

Most phalchas were constructed as an endowment to achieve punya (merit), a prerequisite for salvation. Constructing a phalchas was understood as gifts to society in the memory of a deceased member of the family. Images of gods and goddesses were placed on the rear walls, with an inscription from the donor.

The mandapa phalchas serve independent roles and are free from religious contexts. Mostly called sorakhutte patis, or sixteen-legged resting places, they were strategically placed at entry points of the cities. The mandapa phalcha at Paknajol, Kathmandu, commonly referred to as Sorakhutte Pati, and that at Pulchowk, Patan, no longer exist. The name Sorekhutte Pati is a term adopted during the Rana regime, previously they were referred to as mandapa phalcha.The one at Kirtipur is called Amalachi phalcha, literally meaning a phalcha by the side of a custom office. Those situated at the entry points served the dual function of a custom office and a resting places for weary travelers.

Resting places have been part of the Nepali culture in the hills and the terai; in Kathmandu Valley, they are artistically constructed with bricks, stones, and wood. The local craftsmen took special care to carve the wooden posts and brackets to make beautiful aesthetic architectural features dotting lanes and side lanes. In older parts of the valley, the early morning sun invites the bespectacled senior citizens, clad in tradition labeda suruwals, to the welcoming phalchas, where they become engrossed in conversations or discussions of world events. Such lovely sights are getting rarer nowadays with the sad state of the phalchas, many which have been dismantled, and many that have not been restored by the concerned authorities.

The author is a scholar in Nepalese culture, with special interest in art and iconography. She can be reached at swostirjb@gmail.com

(The second and the third photo used in this article are credited to Sukra Sagar Shrestha)