An adventurer who came to Nepal after traveling around the world, and decided to make it his home, and where he became a celebrated tourism pioneer.

In a short story called “The Verger”, by Somerset Maugham, a church caretaker is sacked because he is illiterate. The unemployed man goes looking for a cigarette, but finds none in his area. Inspired, he opens a shop that sells cigarettes, and it is so successful that in 10 years he has 10 shops. That is when his bank manager finds out that he cannot read and write. “You are so successful without even reading. What would you be if you could read?” the astonished manager asks. “Simple,” says the caretaker, “I would still be sweeping the church.”

The story of Boris Lisanevich begins on a somewhat similar note. No, he was not a church caretaker to begin with. He was a blue-blooded youngster living a luxurious life in Ukraine. Then, the Russian revolution happened, and all but one of his brothers was killed. While his brother went to France, Boris became a ballet dancer and toured Europe. One may imagine that if Boris had stayed in Russia, he would have enjoyed a princely life as a member of aristocracy. But that life would be nothing as compared to the life he came to lead in exile. Beginning his career as a ballet dancer, Boris went all over Europe, then Indonesia, Vietnam, South America, India, China, and America, before finally settling down in Nepal.

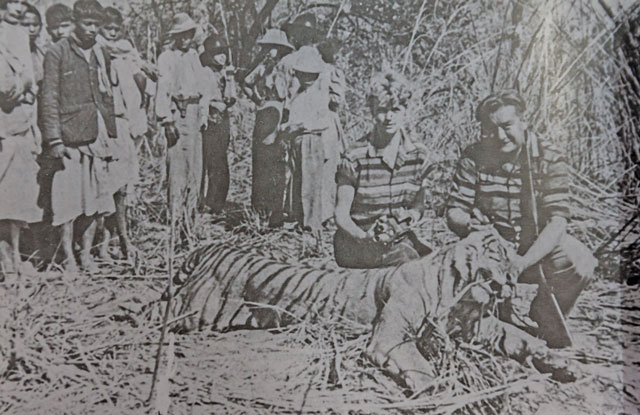

Even before he came to Nepal, his life was already legendary. Apart from his stellar dancing career, he was also a hunter, and had to his credit numerous tigers and rare animals. His most recent accomplishment had been the Club 300, an exclusive club in Calcutta that accommodated no more than 300 people at a time. Like everything Boris did, the Club too was an instant success. It counted among its patrons the wealthiest and most debonair Indian kings, as well as an exclusive expat community. His stint at Club 300 introduced him to King Tribhuvan, who invited him to come to Nepal.

Even before he came to Nepal, his life was already legendary. Apart from his stellar dancing career, he was also a hunter, and had to his credit numerous tigers and rare animals. His most recent accomplishment had been the Club 300, an exclusive club in Calcutta that accommodated no more than 300 people at a time. Like everything Boris did, the Club too was an instant success. It counted among its patrons the wealthiest and most debonair Indian kings, as well as an exclusive expat community. His stint at Club 300 introduced him to King Tribhuvan, who invited him to come to Nepal.

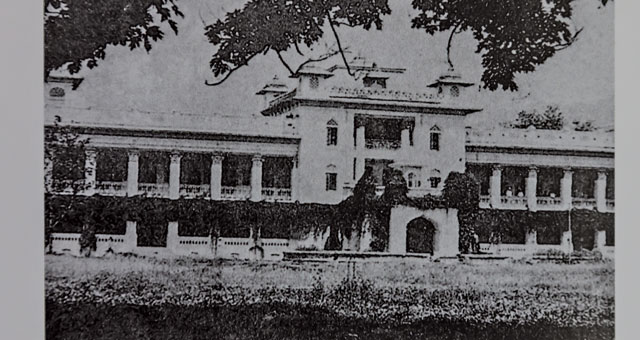

Back then, Nepal was still a pristine kingdom untouched by modernity, and foreigners were still banned. Boris opened the first-ever Western style hotel in Nepal, the Hotel Royal that was located in the present Election Commission building. Running this hotel was no joke, Boris had to import everything from furniture to commodes on the back of coolies–Nepal had no motorable roads to link it to the outside world. “They had the toilets, but no overhead tanks. If anyone flushed, the water had to be poured by a person from above,” says Kabita Lisanevich, the wife of Boris’s second son Alexander.

Every little task at providing modern amenities was a struggle because of Nepal’s isolation. Michel Piessel writes in Tiger for Breakfast, a biography of Boris, that every morning, large bundles of firewood would be delivered to the hotel. The wood was chopped to tiny pieces, and then distributed among the hotel rooms where guests could use it to heat water. Because there was no system to heat water for baths, every room had its own little wood stove. This meant that if you wanted a hot bath, you had to give notice a couple hours before so the water could be ready.

Despite the trials, Hotel Royal was a hotbed of activities. It was here that the earliest of mountaineers met and lived, in the then fledgling industry of mountaineering in Nepal. Boris was on first name terms with all the famous mountaineers of the day, including Edmund Hillary. After he found out his interest in beekeeping, he got Hillary to breed bees in Nepal. Mountains like Annapurna and Everest were conquered for the first time with Boris’s hotel as the base, and the climbers did not forget. Many of them brought back mementos for him: stones from the peaks. Kabita still has the collection of stones from mountains including Everest, Annapurna, Dhaulagiri, Makalu, etc.

Despite the trials, Hotel Royal was a hotbed of activities. It was here that the earliest of mountaineers met and lived, in the then fledgling industry of mountaineering in Nepal. Boris was on first name terms with all the famous mountaineers of the day, including Edmund Hillary. After he found out his interest in beekeeping, he got Hillary to breed bees in Nepal. Mountains like Annapurna and Everest were conquered for the first time with Boris’s hotel as the base, and the climbers did not forget. Many of them brought back mementos for him: stones from the peaks. Kabita still has the collection of stones from mountains including Everest, Annapurna, Dhaulagiri, Makalu, etc.

Kabita also has a substantial collection of books autographed and given to Boris by famous writers that he was friends with. Among them is the writer Han Suyin, whose semi-autobiographical book, The Mountain is Young, is hailed as a realistic description of Nepal in the 1950s. Boris and his second wife Inger (famously called ‘Nordic goddess’ in the book) made it to the pages of the book itself, as centers of the small circle of foreigners and elite Nepalis then. So small was the circle that “if Boris wanted to do any official work or get his passport stamped, the officials would come home,” recounts Kabita from the memories of her husband.

Kabita also has a substantial collection of books autographed and given to Boris by famous writers that he was friends with. Among them is the writer Han Suyin, whose semi-autobiographical book, The Mountain is Young, is hailed as a realistic description of Nepal in the 1950s. Boris and his second wife Inger (famously called ‘Nordic goddess’ in the book) made it to the pages of the book itself, as centers of the small circle of foreigners and elite Nepalis then. So small was the circle that “if Boris wanted to do any official work or get his passport stamped, the officials would come home,” recounts Kabita from the memories of her husband.

Boris is credited with enlarging this circle to include more foreigners. That was a time when visas were not given to foreigners, and Boris had to press Nepal administration hard to give visas to an initial group of tourists. He organized the first handicraft exhibition for them at his hotel, which became a big hit—everything was taken up. King Mahendra immediately ordered that visas be issued to any foreigner who applied, thus opening the doors of tourism for Nepal. But even before this, Boris had already managed to impress Nepali royalty. As the only Western-style hotel in town, Hotel Royal was given the responsibility of accommodating all foreign dignitaries and journalists for the coronation of King Mahendra in 1956.

Boris is credited with enlarging this circle to include more foreigners. That was a time when visas were not given to foreigners, and Boris had to press Nepal administration hard to give visas to an initial group of tourists. He organized the first handicraft exhibition for them at his hotel, which became a big hit—everything was taken up. King Mahendra immediately ordered that visas be issued to any foreigner who applied, thus opening the doors of tourism for Nepal. But even before this, Boris had already managed to impress Nepali royalty. As the only Western-style hotel in town, Hotel Royal was given the responsibility of accommodating all foreign dignitaries and journalists for the coronation of King Mahendra in 1956.

Curiosity in this hitherto forbidden kingdom was high, and the international community responded enthusiastically to the invitations to the coronation ceremony—190 dignitaries arrived, where only 112 were expected. Not just the number of visitors, but many other things taxed Boris’s managing capacity to the fullest at this time: due to a train delay, the food that he ordered from India arrived in disastrous condition. All of the Becti fish that he had ordered died, less than half the chicken made it through, and nearly all the ice that he had carted (because there was no way to make ice in Nepal) had melted away. Boris hastily improvised by buying local chicken, boars, and deer to complete his supply of meat, limiting the use of ice, and in a stroke of genius, molding canned salmon to look like Becti (legend has it that he received a lot of compliments for the unique flavor of the Becti).

Curiosity in this hitherto forbidden kingdom was high, and the international community responded enthusiastically to the invitations to the coronation ceremony—190 dignitaries arrived, where only 112 were expected. Not just the number of visitors, but many other things taxed Boris’s managing capacity to the fullest at this time: due to a train delay, the food that he ordered from India arrived in disastrous condition. All of the Becti fish that he had ordered died, less than half the chicken made it through, and nearly all the ice that he had carted (because there was no way to make ice in Nepal) had melted away. Boris hastily improvised by buying local chicken, boars, and deer to complete his supply of meat, limiting the use of ice, and in a stroke of genius, molding canned salmon to look like Becti (legend has it that he received a lot of compliments for the unique flavor of the Becti).

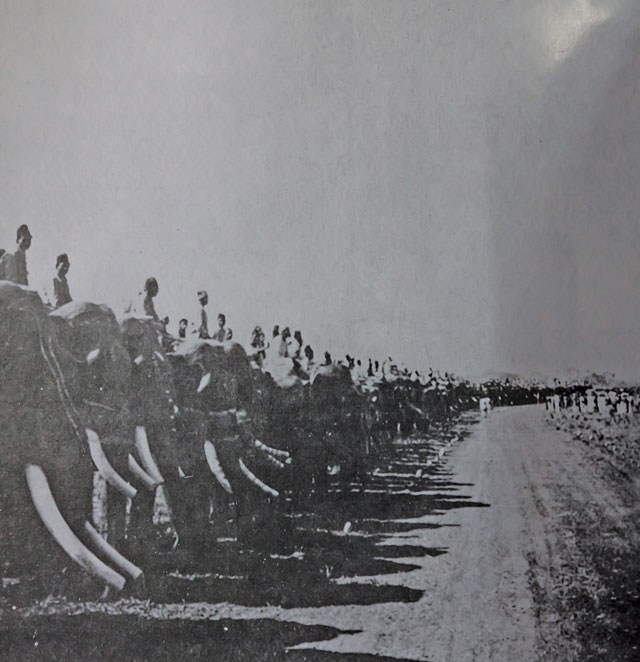

For Queen Elizabeth’s visit in 1960, Boris was given the responsibility by King Mahendra to arrange living quarters for the visiting dignitaries, and to prepare their food. And, once they were back in Kathmandu, he was again given the responsibility, by the British Embassy, of catering for the ball that the queen was to give. Boris excelled at both his duties, erecting palatial camps, including arched doors at the hunting ground in the Terai for the visiting party as well as press. The tent for the queen and her consort comprised 11 rooms, complete with passages. This time, the bathroom had working flushes. There was even hot water for baths, constantly heated on large open fires. The entertainment included hunting, and an assemblage of more than 100 elephants to greet the queen. The food included more than 19 different varieties of birds, some of them very rare.

For Queen Elizabeth’s visit in 1960, Boris was given the responsibility by King Mahendra to arrange living quarters for the visiting dignitaries, and to prepare their food. And, once they were back in Kathmandu, he was again given the responsibility, by the British Embassy, of catering for the ball that the queen was to give. Boris excelled at both his duties, erecting palatial camps, including arched doors at the hunting ground in the Terai for the visiting party as well as press. The tent for the queen and her consort comprised 11 rooms, complete with passages. This time, the bathroom had working flushes. There was even hot water for baths, constantly heated on large open fires. The entertainment included hunting, and an assemblage of more than 100 elephants to greet the queen. The food included more than 19 different varieties of birds, some of them very rare.

The queen responded by stating that it was “one of the most exciting days of her life.” And, of course, later Boris catered with the same level of excellence for her ball in Kathmandu. By this time, Boris’s fame had grown so much that Prince Philip, the queen’s consort, asked him, “Are you Boris?” and proceeded to tell him how much he had heard of him. Indeed, his fame was so great, it was said that he was second only after Everest in attracting people to Nepal. There were rumors that Elvis Presley had wanted to visit him, but that did not materialize. But, even without Elvis, he did not lack from famous friends, having catered to world-famous personalities like astronaut Valentina Tereskova, the first woman in space.

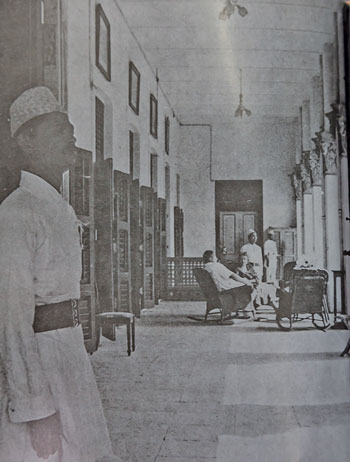

His life is also a window into the Nepali society of the time. Eventually, he left Hotel Royal to open a restaurant, Yak & Yeti, in Durbarmarg. (Today the restaurant is known as Chimney, while the hotel in which Chimney is located has taken over the name Yak & Yeti). Though his restaurant was a roaring success, dignitaries and diplomats could be seen sitting morosely at the bar, drinking juice, because the plane carrying alcohol was held up due to tax reasons. Nepal was still struggling through the modern wrangles of customs, import, and export back then.

In the center of all this was Boris, an extremely social man with a large heart. The rotund man with a large belly always wore colorful bush shirts that reflected his easygoing nature. He was always ready for a laugh and a drink, and made no distinctions of hierarchy. Even though he lived and breathed with royalties, he was just as courteous to these below him. Those who know him remember him treating the entire restaurant to dinners if he was in a good mood, and a party for every guest at their arrival was the norm (some say his biggest PR weapon). Many of them he housed for free, including Michel Piessel, the writer of his biography.

“He was not a family man. If the family was having dinner, and Boris saw people he knew, he would invite them all to join the table,” Kabita quotes Inger, Boris’s wife, who passed away in 2013. No wonder Inger was frequently heard to complain that she had only spent two evening alone with him in their entire married life.

One would think that a bustling hotel would be enough to occupy Boris, but Boris was not one to be limited. His interest in food and beverages also included agriculture; he was the one who introduced white pigs to Nepal. The story of their introduction is actually hilarious. Boris had found quarters for the pigs at Ichangu, but the pigs refused to walk uphill. The steep, narrow roads made carrying them impossible. They kept pulling at the ropes and walking backwards. He solved the problem with customary creativity: he turned them around and pulled them downhill. They walked backwards all the way.

Boris is also credited with introducing many produces to Nepal, including strawberries and beetroots. Today, Philippe Belhay, the general manager of Yak & Yeti, has recreated Boris’s garden in the hotel’s backyard. “We have planted everything that Boris first brought to Nepal,” he says. The hotel uses this produce. Chimney holds a ceremony every November in honor of Boris, when the Russian ambassador is invited to light the fire. Every month, in his memory, a Russian night is held to improve cultural relations between Nepal and Russia. “Boris is an inspiration to anyone in the tourism industry,” says Philippe. “He inspires a foreigner like me to contribute to Nepali tourism in the same way.”

But his contributions were not limited to the tourism industry. At some point, he had found time to found Cathay Pacific airline. He was the first person in Nepal to get a license to buy and sell alcohol, and the first to open a slaughterhouse. “He was so dynamic that he would dabble in everything, say no to nothing,” says Kabita. Even his biographer, Michel, was astonished at the amount of information he kept unearthing on Boris. “I thought I knew everything about him, but every time I looked, I found more things he had done. And each was more fantastic than the previous,” he concludes. With a man who raised deer and pythons for fun, the fantastic was never out of range.

When Boris came to Kathmandu, he was in his forties. But this was the city that he chose to settle down and raise his children in. The government never did anything to acknowledge his contributions (“Forget a medal, he did not even have a Nepali citizenship,” says Kabita). However, his spirit lives on in this city. Among three of his sons, one of them, Alexander, chose to live in Nepal. Alexander’s wife and children are still rooted in Nepal. Yak & Yeti treasures a “Boris tree” that was planted by Boris and that he liked. A bust of Boris can be found in the premises of Tourism Board, along with those of Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hilary, a nod to his enormous contributions to Nepal. And, every visa stamped to a foreigner, or every Western-style hotel in Nepal, owes something to the pioneer who blazed the path for them. Thus, the legend of Boris of Kathmandu survives in this city that was his home till the end of his life.