Like the poets who dream of flowers blossoming in the desert, Toru Kondo, widely known as Kondo Baje, was a poet-cum-pomologist who dreamt of growing rice in the trans-Himalayan arid climate of Mustang. He worked like an artist, bringing together wild and domestic fruits to create new species that flourished in the Nepali market.

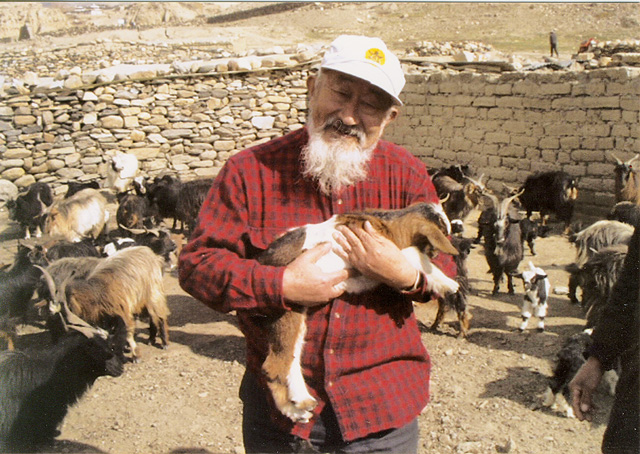

Living under the shadow of Annapurna and Dhaulagiri, Kondo had truly adopted the mountain man spirit. His hair and beard had turned white like the snow peaks surrounding him. Riding on horseback like Clint Eastwood in the classic Westerns, he used to travel on Mustang’s rough terrain carrying a bag full of biscuits and chocolates that he shared among the children who used to follow him wherever he went. “Okay Baje” is what they called him, since he used the word often. Kondo contributed greatly to the education of Mustang’s children. He not only established 17 schools in the region, but also did reconstruction work and provided the required stationary. A large number of students had started leaving the schools and going to monasteries because they were provided with food. In a bid to keep them in school, Kondu started providing free lunch at the schools.

Living under the shadow of Annapurna and Dhaulagiri, Kondo had truly adopted the mountain man spirit. His hair and beard had turned white like the snow peaks surrounding him. Riding on horseback like Clint Eastwood in the classic Westerns, he used to travel on Mustang’s rough terrain carrying a bag full of biscuits and chocolates that he shared among the children who used to follow him wherever he went. “Okay Baje” is what they called him, since he used the word often. Kondo contributed greatly to the education of Mustang’s children. He not only established 17 schools in the region, but also did reconstruction work and provided the required stationary. A large number of students had started leaving the schools and going to monasteries because they were provided with food. In a bid to keep them in school, Kondu started providing free lunch at the schools.

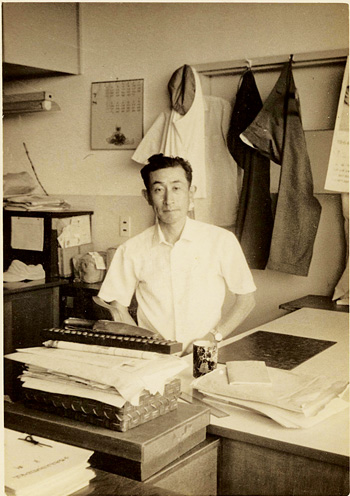

Born in Nigata, Japan, in 1921, he had one elder brother, five elder sisters, and one younger sister. Life as a teenager wasn’t easy for him during the Second World War, amidst the guns and bombs, but he continued pursuing his dream. His love for plants grew when he graduated in horticulture from Niigata Agriculture and Forestry College in 1947. Later, he did research on the Minomiya fruit growing farm situated in the University of Tokyo. He was an assistant professor of horticulture at the Nigata National University for a decade, and chief researcher at Niigata Horticulture Research Center for six years. He then worked as the chief director of the Horticulture Extension Office for 12 years, from 1964 to 1976.

Born in Nigata, Japan, in 1921, he had one elder brother, five elder sisters, and one younger sister. Life as a teenager wasn’t easy for him during the Second World War, amidst the guns and bombs, but he continued pursuing his dream. His love for plants grew when he graduated in horticulture from Niigata Agriculture and Forestry College in 1947. Later, he did research on the Minomiya fruit growing farm situated in the University of Tokyo. He was an assistant professor of horticulture at the Nigata National University for a decade, and chief researcher at Niigata Horticulture Research Center for six years. He then worked as the chief director of the Horticulture Extension Office for 12 years, from 1964 to 1976.

Kondo came to Nepal in 1976 through the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) under the aegis of the Japanese government. There were many experts from Japan who used to come for very short periods of time, but when Kondu arrived in Nepal, he knew he was here to stay. He worked as a pomologist in the JADP (Janakpur Zone Agriculture Development Project). During his five years there, he revolutionized citrus farming in places like Sindhuli and Ramechhap, and conducted research on fruits like orange and lemon. He hybridized wild fruits, self-maintaining their population in natural or semi-natural eco-systems, and cultivated fruits and plant species through selection, or breeding.

Jyotilal Ban, who assisted him at JADP, and the author of “Athak Pathika”, a book on Kondo, dotingly remembers the time working with him. He told me about one incident when Kondu was giving a practical demonstration of planting citrus fruits in Sindhuli. He accidentally walked into some bushy areas where sishnu (nettle) pricked him all over the body, but that did not stop him, and he continued with the demonstration. As a result, he was bedridden for days with fever. However, this experience did not dampen his excitement to disseminate the knowledge that he had, and he continued to teach others.

Kondo introduced a number of techniques of grafting in which a section of a stem with leaf buds is inserted into the stock of a plant. He also worked on fruits such as grapes, mangoes, and lychee. In the past, farmers used to grow fruits only as a medium of subsistence, but Kondo made them realize their true commercial potential through introduction of new innovation and technology. Grapes were considered to be fruits that could be grown only in colder climates, but Kondo dispelled the myth, and mass production of grapes in the Terai region followed. He worked in Chapauli and Ratanchura villages of Sindhuli for mass production of citrus fruits.

Kondo introduced a number of techniques of grafting in which a section of a stem with leaf buds is inserted into the stock of a plant. He also worked on fruits such as grapes, mangoes, and lychee. In the past, farmers used to grow fruits only as a medium of subsistence, but Kondo made them realize their true commercial potential through introduction of new innovation and technology. Grapes were considered to be fruits that could be grown only in colder climates, but Kondo dispelled the myth, and mass production of grapes in the Terai region followed. He worked in Chapauli and Ratanchura villages of Sindhuli for mass production of citrus fruits.

Jyotilal Ban told me another interesting fact about Kondo. “The light in his room was never switched off. One day, I got up and walked up to his room to see what he was doing. He was writing. He enjoyed writing, whether it was poems, articles, or a chapter of his book,” he said. He was author of books like ‘Step by Step and Year by Year’ (1990) and ‘Never Forget My 25 Years Old Friendship’ (2005), among others. He was an also an avid reader, who used to take out a Japanese novel every time he was stuck in a traffic jam.

Kondo first visited Mustang in the 1970s. The cold climate of Jomsom and the warmth of the beautiful people of Mustang engrossed him. His love for Mustang and desire for development in the region was so immense that he wanted to live and work in Nepal after retirement. “I can change this dry, barren land of Mustang into fertile land. The strong sunshine and melting water are precious elements required for agricultural development, which are abundantly available in Mustang,” he said. His vision later became an obsession; he sold all his property and home to establish the Mustang Development Service Association (MDSA). This, unfortunately, caused differences with his wife that led to their divorce in the early nineties.

Kondo first visited Mustang in the 1970s. The cold climate of Jomsom and the warmth of the beautiful people of Mustang engrossed him. His love for Mustang and desire for development in the region was so immense that he wanted to live and work in Nepal after retirement. “I can change this dry, barren land of Mustang into fertile land. The strong sunshine and melting water are precious elements required for agricultural development, which are abundantly available in Mustang,” he said. His vision later became an obsession; he sold all his property and home to establish the Mustang Development Service Association (MDSA). This, unfortunately, caused differences with his wife that led to their divorce in the early nineties.

Despite the turbulence in his personal life, he did not stop pursuing his dream of a fertile Mustang. After establishing MDSA in 1991, for the next 24 years, he worked in sectors such as education, health, agriculture, horticulture, and livestock in the region. He helped to increase the production of apples and other fruits. He also trained the local farmers, and created sample farms to show them the possibilities of production. He planted fruits and other vegetables in the dry land on the banks of the Kali Gandaki River. Apple farming had been present in Mustang for years, but he introduced the concept of mass-production through grafting. He started removing excess seedlings to allow sufficient room for the remaining apple plants to grow, known as thinning in agriculture. He established apple farms in Syaang and Thini, and later passed the farms to the locals.

Although the ‘Forbidden Kingdom’ of Upper Mustang was a restricted area when Kondo started working there, his desire to serve the people allowed him to work there without any problems. His determination won over the hearts of politicians belonging to different political parties. Jigme Palbar Bista, the last king of Mustang, requested Kondo to build a school in Upper Mustang, which he obliged. The people also had little or no access to medical facilities. They had a deep connection with the spiritual world, and believed that a shaman had the ability to communicate with the spirits and heal sickness and disease. But, the shamans’ trance-inducing techniques were unable to cure any of their health problems, and many of them died in the absence of treatment. After seeing this miserable condition of the people, Kondo decided to build a hospital in the region. The result was Ghami Hospital, established in 1998, which had a Japanese doctor, nurses, and an ambulance.

Apar Khadka, the chairperson of Kondo Foundation, knew Toru Kondo since she was seven years old. She disclosed, “Even though he had divorced his wife, he remained close to his three daughters, who used to come to Nepal often. He lived a very simple life. His daughter Naoko was very supportive of his endeavors in Mustang, but unfortunately, she died of an undiagnosed cancer six months before her father.” Kondo was like a grandfather to Apar, who first met him at her sister’s office at JICA. Soon after that, she had many opportunities to travel with him to Japan. Her fluency in Japanese made these trips very fruitful and interesting.

Later on, Apar played an important role in establishing the Kondo Foundation in 2013. Although the foundation doesn’t get the funds like during the time of Kondo, it is still working to continue taking his legacy forward. His last words to her on the telephone were, “Keep on doing the good work. I will see you again.”

Kondo used to speak a mixture of Nepali, Japanese, and English. He had a very good relationship with the Japanese ambassadors over the years. Many of them used to go to Jomsom with him. Apar recalls a time when he invited the Japanese ambassador for lunch, and he was very impressed by Kondo’s cooking skills. Kondo liked eating plain Japanese food without any spices.

The political system in Nepal kept on changing, but that never had any effect on him. He won many awards during his lifetime, including the Suprabala-Gorkha-Dakshina-Bahu (Member Third Class) from late King Birendra Bir Bikram Shah. Although he was offered Nepali citizenship, he preferred serving Nepal as a Japanese citizen.

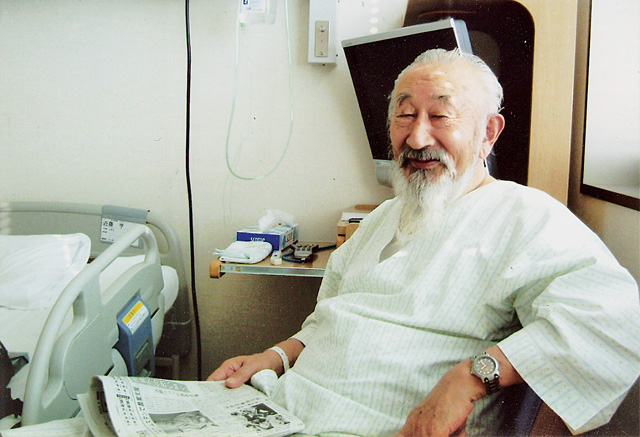

He was diagnosed with intestinal cancer at the age of 88, so he was in and out of Nepal for the last few years of his life. He was still a mountain man at heart, but physically, his days were numbered. The mountains were calling, and he wanted to return back to Nepal. While he was lying on his hospital bed, he wished to die in Nepal, and have his remains buried under the land of Mustang, which he had adopted as his second home.

He had a vision that rice could be grown in the harsh climate of Mustang using greenhouses. He was successful in proving this, but it wasn’t easy for a normal farmer to replicate his work. Unfortunately, his dream couldn’t be converted into reality, as he passed away on June 9, 2016, at the age of ninety-four. Although he died miles away from Mustang, his last wish did indeed come true, as half of his remains have been buried under an apple tree in the apple farm he envisioned, whereas half is planned to be placed on the premise of Ghami Hospital in Upper Mustang.