Juggling between conserving heritage and the need for modernization is by no means a small feat. Concerned citizens, organizations and even the government is doing their best to preserve it for posterity.

A Rude Awakening

August 2014 brought an interesting discussion regarding Nepali heritage in the national limelight. Three months before the story got traction in Nepali social media landscape, French graffiti artists had painted the ancient Purohitghat Sattal in what Rabi Thapa, who wrote the story for Lalit Magazine, calls a cartoonish, technicolor hues. A flurry of events unfolded after the story was reported – City Museum organized a discussion session about the issue, and for a while it exploded into our collective Facebook feed.

There were angry—vitriolic even—comments, accusations flew left, right and center; the act was paraded as new form of colonialism – see, how easy for a Westerner to waltz into our heritage site and deface it on a whim? The artist, on his site, and on the comment thread in the Lalit Magazine’s website brushed it off saying that a caretaker sadhu had asked him to brighten up the building, a purpose he carried to his heart. Buried somewhere in the avalanche of chest-pounding indignation was a gem of a comment. In it, evidently written in the heat of the moment, someone mentioned that such acts would strife nascent art scene in Nepal. It could have easily passed as a satire, except it wasn’t intended as one. The writer really was worried strangling the nascent art scene in Nepal, than was for the loss of heritage.

There were angry—vitriolic even—comments, accusations flew left, right and center; the act was paraded as new form of colonialism – see, how easy for a Westerner to waltz into our heritage site and deface it on a whim? The artist, on his site, and on the comment thread in the Lalit Magazine’s website brushed it off saying that a caretaker sadhu had asked him to brighten up the building, a purpose he carried to his heart. Buried somewhere in the avalanche of chest-pounding indignation was a gem of a comment. In it, evidently written in the heat of the moment, someone mentioned that such acts would strife nascent art scene in Nepal. It could have easily passed as a satire, except it wasn’t intended as one. The writer really was worried strangling the nascent art scene in Nepal, than was for the loss of heritage.

That any building or a monument, once its age exceeds a hundred years, is deemed as a national monument and is protected by Ancient Monuments Act, first promulgated in 2013 BS, and defacing such monuments is a criminal offence was hardly mentioned. Nor was the idea of cultural identity and how we relate to our heritage . Credit where it is due - Rabi Thapa mentions it in his story, but only in passing; the gist of the story focuses on what the act of vandalism translates to in our context. As it turns out, it translated into nothing except a few heated comments.

Since the artist in question is not facing any kind of criminal inquiry as the above-mentioned provision stipulates, it can be inferred that our government or the concerned authorities are either not interested to protect our heritage, or so caught up in intra-departmental quandaries that they are close to paralyzed. However, it did bring a really interesting question in the public limelight – if the government is not pulling its weight then who really is responsible for protecting our heritage?

A Delicate Balance

In 1970, Joni Mitchell wrote a song that best surmises one of the biggest issues of heritage conservation in Nepal. “You don’t know what you’ve got, till it’s gone,” she wrote. “They paved paradise and put up a parking lot.” We have, all in the name of development, paved paradise to put up a parking lot. Consider a few cases.

In 1993/4, during the construction of the Bagmati Bridge in Thapathali, the government tore down a historic temple and a pati. What remains of the complex is cramped away in one corner. The government had assured the public that those structures will be relocated with due honour as it merits a place of worship. Twenty one years hence, the promise still hangs in the air.

The recent road widening also has upset conservationists and heritage practitioners, common people notwithstanding, at how the government has treated places of utmost importance. While widening the Sano Gaucharan section, the concerned department chopped down a poplar tree. In Hinduism poplar trees are considered sacred and offering puja to a poplar tree, it is believed, grants religious merit. The department was having none of it. After hacking the tree to a manageable size, they had it bulldozed.

As the stump, along with the root was being bulldozed, the workers chanced upon an archaeological pot of gold - they unearthed a Shiva Linga dating back to the Lichhavi period; it was lodged firmly in the ground. Let it sink in - a Shiva Linga from the said period is indeed a rare find. Historians salivate even at the thought of such a find. The workers were having none of that, too. They bulldozed all over the place, after plucking the sacred object like any other inconsequential pebble from the road. They did carve out a niche to establish the venerable object, but the manner in which this was done offended lot of people. One of them was Prof Dr Sudharshan Raj Tiwari. For him, it was a slap in the face.

“The site merited a serious study,” says Dr Tiwari. “Constructions from Lichhavi dynasty follow a specific rules - the stone base, atop which the statue sits, is constructed in a specific way and is followed by a prathisthapa puja before the statue is consecrated. We could have unearthed period coins or other types of religious offering devotees might have made in the shrine. It could have expanded our knowledge of that era.” Blatant disregard for an archaeological site and the deftness with which the government treated religious icon ticked the local community off.

This type of heavy handedness in dealing with our heritage is not new, sadly. A monument of great historic value rests unceremoniously in the Nach Ghar building in Jamal. It looks wildly out of place, surrounded with the concrete structure that makes the building. Just adjacent to its parking lot, and a few feet away from the staircase to the hall lies the four-faced (chaturbyuha) statue that, according to heritage expert Rabindra Puri, dates back to the 1st century AD. The statue is important not only because it dates from the first century, but also because it is one of the first such chaturbyuha murtis in Kathmandu. What makes it unique and rare is that the deities that are carved in the four cardinal directions are: Vishnu, Brahma, Shiva and Shakti. Consider that. And, keep in mind that any iconography of Brahma is rare indeed, and is seldom seen with other deities.

Icons and structures from Malla times are not faring better either. Recently, another important structure dating back to the Malla era was martyred in the name of road widening. The historic structure gives Sorahkhutte its name. The pati is famed for, among other things, providing a resting place for Prithavi Narayan Shah who took time off to tend to his wounds from his campaign to conquer the Kathmandu Valley. It was also the point where Lhasa traders converged before and after their trip. As in the case of Bagmati Bridge, the concerned government authorities have assured the pati will be restored in ‘an appropriate place’.

Icons and structures from Malla times are not faring better either. Recently, another important structure dating back to the Malla era was martyred in the name of road widening. The historic structure gives Sorahkhutte its name. The pati is famed for, among other things, providing a resting place for Prithavi Narayan Shah who took time off to tend to his wounds from his campaign to conquer the Kathmandu Valley. It was also the point where Lhasa traders converged before and after their trip. As in the case of Bagmati Bridge, the concerned government authorities have assured the pati will be restored in ‘an appropriate place’.

Seeing how badly prime examples of the art and architecture from our history are treated, one cannot help but ask this question: Whose Heritage is it anyways?

“Of course, ours,” says a source. The said individual works with the Kathmandu Municipality and requests not to be named. The nature of the individual’s work is such that it demands working closely with all the stakeholders responsible for maintaining and up-keeping the heritage within the municipality’s jurisdiction. “The lack of communal awareness about the importance of our heritage and the government apathy is such that no one is willing to come forward to conserve it. It is our collective responsibility.” The source points out to the ambiguity in our laws for the government’s inaction. “It is not clearly spelled out which government bodies and line agencies should be doing what,” the source continues, “And that adds a lot of confusion.”

“Ancient Monuments Act tasks the Department of Archaeology with the task to preserve the heritage, while the local governance law identifies the role of municipal bodies to take charge,” the source adds. “This makes it easier for each department to shrug off from their duties and point towards other departments and ministries when the issue comes up.”

The Need for Conservation

The Need for Conservation

Given how tricky balancing the leap to modernisation and protecting heritage is, and if development really is all about discarding the traditional for the new, then why conserve at all?

“It’s our identity, that’s why,” says Rabindra Puri, a heritage architect who has devoted his life to documenting and saving our heritage. His works, especially the Namuna Ghar in Bhaktapur, illustrates that protecting our heritage is not only approachable but financially viable too. Currently he is involved in numerous projects, which he hopes, will pave for a better understanding of how our heritages can be adapted to changing times.

Puri brushes off Kathmandu’s fascination with modernisation, especially our appetite for cemented structures that is threatening to replace traditional architectural motifs from the valley. He is appalled by our apathy to conserve our built heritage.

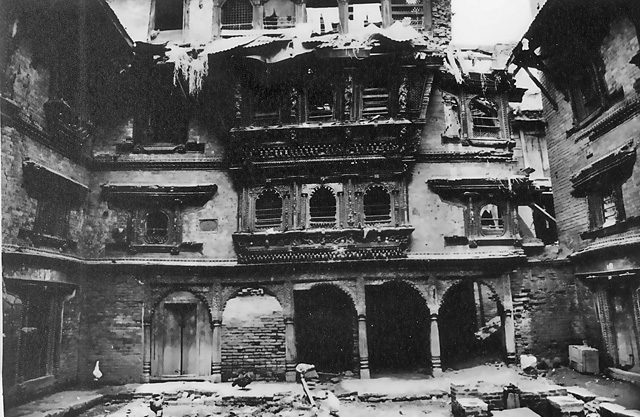

Built heritage in Kathmandu is the tallakar temples (Tallakar temples are what Prof Dr Tiwari calls what we know as the pagoda styled temples), the granthakuta temples (again, those are what Dr Tiwari calls what we generally refer to as the Shikhara style temples, the best example of which is the Krishna Mandir in Mangal Bazaar), royal palace complexes (such as in the three Darbar Squares), ancient houses—with intricately crafted windows, sloped roofs with struts—and the kind of structures that was once prevalent in the valley.

“Kathmandu’s built structure is our heritage and is an intricate part of our social landscape. It forms the basis of our identity,” he says. “It the where our civilisation reached its apogee, and manifested itself. Our built structure is the result of the continuous evolution of our architecture, hence suits our climatic condition, is strong and absorbs and handles seismic shock better than other structures.”

Despite these seemingly obvious plus points, why aren’t more individuals and communities rallying up to save it? “It’s the lack of awareness,” he says. Alok Siddhi Tuladhar, who heads the ImPACT Productions and is one of the upcoming advocates for conserving our heritage, believes that to be case too. “The lack of awareness can be detrimental,” he continues. “Apathetic community and the lack of strong initiations from the governing body is partly responsible for the loss of our heritage.”

Tuladhar veered from the course of a ‘normal’ career after witnessing the destruction of our collective heritage. “It is essential that the communities appreciate and understand the value of heritage that surrounds them,” a monumental task that he and his team is doing through social media and various campaigns they have organized over the years. Dive deep in the group’s Facebook page and you’ll see how they are creating a platform for the youth to be interested in protecting their heritage.

“Eventually, the young people will have to take the mantle of preserving their heritage,” he says, “And we are facilitating this conservation through the medium they understand the best, which is through social media.”

Conservation through Conversations

Few months ago, ImPACT Productions Facebook page announced a workshop to document historic heritage houses in Kathmandu. The program was jointly organized by the Department of Archaeology, Kathmandu Metropolitan City, The Explore Nepal Group, Rabindra Puri Foundation, Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust and ImPACT Productions – displaying a rare and much needed public private partnership for heritage conservation. The social media call didn’t get much attention and even the organizers hadn’t expected such a turnout. On 29th January, when the first phase of the Heritage Documentation Program started, participants poured in like rain. “When we initially conceptualized the program, we had hoped for at least ten individuals,” he says. “It was so reassuring to see that there were people who still cared about conserving their heritage.”

More than fifty persons showed up for the program. Rabindra Puri was also there as a resource person, so was Prof Dr Tiwari along with officials from the heritage wing of the Kathmandu Municipal City.

Bharat Basnet, hotelier and heritage conservationist who converted the private house of Shree VI (yes, Shree VI) royal priest into Bhojan Griha, shared his experience of how uphill a battle it was for him to conserve that heritage house. In the similar vein, Rabindra Puri spoke at length about the ideas behind conservation and the efforts his foundation is doing to save our heritage. Prof Dr Tiwari talked about how to identify a heritage house and how best to document those. Noted heritage architect Dr Rohit Ranjitkar of Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust (KVPT) led the second leg of the workshop and supervised a team of more than twenty architects to make an inventory of heritage houses.

Programs such as these are important not only that they bring such resource persons with vast and diverse knowledge in one gathering, but also provide a forum where the younger generation can learn about our heritage and why it is important to conserve them. More and more of these kinds of conversations need to happen if we are to impart the value of our heritage to the younger generation.

One such effort is taken by an entity that you’d never suspect. The Kathmandu Municipal City has created a youth club called Sama YuBaa and the members of this club regularly host a heritage walk in the city. Led by heritage experts, the participants learn in depth about our heritage. “Knowledge is the first step towards conversation,” says Tuladhar. “Only when we understand and appreciate the value that surrounds us on all sides will we be motivated to conserve it.”