A home where children beat the odds at play

Two months ago a boy from my hometown with whom I had spent many evenings on the playground met with an accident, and in its aftermath, one of his arms had to be amputated. I felt uneasy going to visit him at the hospital. I had a stifling feeling: What could I say?

Upon seeing his emaciated body, I smiled feebly. Although heavily drugged, he returned a beaming smile. Within minutes, he got to reminiscing about our cricket games and joked about his rough handling by the nurses. In doing so, he not only lessened my burden - something experienced by anyone visiting a victim of a tragedy – but he did more; he prevented me from being uselessly sorry. In fact, he made me happy by being happy, by stoically giving my visit more significance than his own problems. He lost an arm, but none of his jovial nature, wit or his smile. Mentally, he’s stronger than ever. Whenever I visit him, he has on display the secret of good living—enjoying life.

Upon seeing his emaciated body, I smiled feebly. Although heavily drugged, he returned a beaming smile. Within minutes, he got to reminiscing about our cricket games and joked about his rough handling by the nurses. In doing so, he not only lessened my burden - something experienced by anyone visiting a victim of a tragedy – but he did more; he prevented me from being uselessly sorry. In fact, he made me happy by being happy, by stoically giving my visit more significance than his own problems. He lost an arm, but none of his jovial nature, wit or his smile. Mentally, he’s stronger than ever. Whenever I visit him, he has on display the secret of good living—enjoying life.

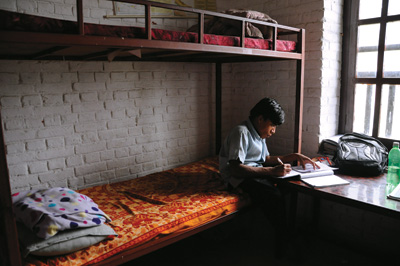

The Disabled Rehabilitation Center (DRC) in Gokarna, north of Boudhanath has 56 children of a similar mettle. Not all of them however, have physical disabilities. About 25 percent of the children are there because they come from very poor families, or remote areas. “In taking in a child who does not have a physical disability”, explains Amrit Pudasaini, DRC’s secretary, “we give priority to children from the hills.” Irrespective of where they’re from, the long, double-storied DRC building is now their home and its inhabitants their family.

The idea of a rehabilitation center for children with physical disabilities was conceived by Tanka Tiwari, who himself had a physical disability. In 2002, he along with other founding members established DRC in Gaushala. When DRC opened, it had five children. During the first few years, the center changed locations constantly, mostly to meet the need for space to accommodate growing numbers of children. Finally, in 2006, it opened at its present location in Gokarna, with 32 children. Since 2002, more than 50 have moved on having completed their rehabilitation period and deemed capable of making it on their own.

The numbers are not the only thing on the rise at the center; the majority of the children, even in the absence of advanced physiotherapy, or any other special medical assistance, rise to new heights, physically and mentally. Twenty-four year-old Wangchuk is the center’s only resident with a mental disability and its greatest success story. He belongs to a very poor family from Solukhumbu and thus the center made an exception, taking him in at no cost. His progress has been exceptional. Pastemba Sherpa, the hostel in-charge, kitchen helper, and everybody’s “uncle” at DRC relates the healing effect the center has had on the boy. “When Wangchuk first came here, he salivated incessantly. He couldn’t hold up a plate of food. He just sat around, too weak to even lift his head. Today he carries buckets of water, attends to various chores, and helps everyone out.” Nearby, Wangchuk clapped his hands gleefully, as if to corroborate what Pastemba had just said.

One day, when it began raining, I saw Wangchuk rush out and collect the clothes belonging to the other children. When he opens the gate to someone, he welcomes them with a broad smile and a Namaste — his ability to make people feel welcome and special is remarkable. He never forgets to shut the door behind you (his duty at DRC), or to request you to visit again.

The Stages of Rehabilitation

of Rehabilitation

When new children are admitted the goal is to get them to the highest level of physical well-being possible. “We try to treat the children’s physical problems to the extent that health facilities in Nepal allow,” says Amrit about DRC’s treatment procedure. The belief is that children with disabilities need a good start if they are to be rehabilitated successfully. Physical well-being is one of the cornerstones of rehabilitation. Operations, medication and physiotherapy are all part of the treatment, which have produced wonderful results for some children, allowing them to do well in other aspects of rehabilitation.

All that is done for a child at DRC is done considering their future, and there is no better way of ensuring a better future than through education. DRC sends all its residents to school: some on scholarship, some on discounted tuition, and some directly supported by individual sponsors. It is not just about ensuring an education but giving the children quality education. Only a few children attend special schools like Nawa Jeevan, which are for the physically disabled; the majority are enrolled in private schools.

In school, it is not the physical disabilities that set the children of DRC apart — it is their academic performance. “Disabled children here do better academically then those without,” says Amrit Pudasaini. He believes it is the environment at the center that accounts for this. Living with physically able children, he explains, develops confidence in the disabled child, leading to academic success. Last year, two girls from the center appeared in the SLC (School Leaving Certificate) examinations, one of whom passed and is now studying with a government scholarship. Three more will appear this year. “There is no doubt that these three are going to be successful. All of them have been topping their classes,” says Uday Bahadur Limbu, DRC’s chairman, flashing a confident smile. Although children are no longer eligible to reside in the center after the completion of their SLC exams, they continue to receive help from DRC in the form of assistance in obtaining scholarships and admission into colleges.

The staff at DRC is aware that not every child prospers academically. Skill development is an alternative means of securing independence for those that do not show promise in academics. The center, therefore, runs a three-month training program in tailoring. There are also classes in computer skills. Acquiring a special skill gives the children the basis to succeed in the latter stages of the rehabilitation process. It also makes it easier for DRC to find jobs for the children. The training on tailoring, unlike the computer training, is open to non-residents who have physical disabilities, are orphans, or socially disadvantaged. Special priority is given to disabled women for the training in sewing and dress making. Many people have benefited from these training programs. Last year DRC trained 40 people, many of whom today run small businesses of their own, or are employed by others.

The final goal of DRC is to rehabilitate the children back into their families. In situations where this is not possible, the children are rehabilitated in the community, which means finding them a job in their community. If both of these forms of rehabilitation are not feasible, jobs are sought for the children locally, in Kathmandu. So far, if the rehabilitation criteria of education, post-treatment rehabilitation, and skill development are considered, DRC has rehabilitated 18 children.

Reaching Out

“There are around 200 applicants waiting to be admitted into the center, but every year only two or three children leave the center,” says Limbu, explaining the organization’s limitation and predicament. DRC, however, does not confine its services to the center’s residents; it reaches out to serve children outside the center. Currently DRC sends 55 children to schools and colleges. It also makes recommendations, negotiates discounts on school fees, coordinates for admission at schools in the area where the children live. DRC also helps the children gain access to health facilities. Liaising with hospitals and various organizations, wheelchairs, crutches, and other equipment are provided to those who need them.

Arrangements have also been made with certain hospitals for providing special discounts on treatment fees. Over 70 non-residents benefit from DRC’s services. The organization’s mandate limits its concerns to the disabled, orphans, or socially underprivileged individuals. But even those that are not physically or socially disadvantaged are helped through DRC’s many training programs.

Keeping the Organization on Its Feet

Keeping the Organization on Its Feet

DRC has no permanent source of funds. It is dependent on individuals for donations of funds, food and clothing, and it counts on their generosity to pull them through. They raise funds through membership fees and a door-to-door collection program, the latter being their largest source of steady income. Sporadic and meager but welcome funds are also generated through the organization’s international volunteer program, which allows international citizens to volunteer by paying a certain amount of money. Under this program the Hope and Home Volunteer Organization facilitates the services of international volunteers to DRC. The volunteers mostly help the children with their studies and join them in play, and are sources of what most children love—photos. Many volunteers continue to raise and send funds from their home countries after leaving Nepal. More than 60 volunteers from countries like USA, UK, France, Germany, and Holland have come to work in DRC over the years.

Opportunity Not Sympathy

Sympathy is the last thing Pudasaini wants for those with physical disabilities. “The children should not only be treated as objects of pity”, he stresses. He believes they each need opportunity. “Create it!”, he says passionately, alluding to the responsibility of the government and the society in creating an environment for the disabled to make progress as individuals. I ask him how that can be done. There are three steps, he says. First and foremost: availability of free treatment. Second: education. Third: employment. Pudasaini, and others at DRC are dedicated to paving the way for the disabled to achieve independence. They expect the same from the government.

Pudasaini believes if the government was to look after the education and health of those with physical disabilities, their lives would change significantly. “If you treat disabled people, I believe about 30 percent can become able again”, he claims. For that to happen, he believes all hospitals should provide cost-free treatment for the disabled. He does not believe reservation is the answer; a few seats here and there will not be effective unless complemented by others facilities. For example, reservation in a college for the disabled is laudable, but unless accompanied by a scholarship it loses its efficacy. “There are separate seats for women and the disabled in a micro bus, but how many times do we see women and those with disabilities occupying those seats? On the contrary, we see women standing”, he says to explain his point. He stresses it is the society’s perception that needs to change as much as the policies. Opportunities for the disabled are needed instead of public sympathy.

The children of DRC, like the nearby forest of Gokarna, the eagles wheeling overhead, and the relatively clean Bagmati flowing nearby, all symbols of hope for greenery, wildlife, and a clean city, represent the spirit of fighting the odds. While they wait for the people at the decision-making level to create opportunities for them, in their own way they provide us with opportunities to witness the power of the human spirit.

Nepal’s Disabled Rehabilitation Center (DRC) can be contacted at rehab@drcnepal.org, or in Kathmandu phone 480.0867. You can visit their website at www.drcnepal.org. For more about the Hope and Home volunteer program for Nepal, see www.hopenhome.org/contact.htm The author is a freelance writer who can be contacted at papercloudtree@hotmail.com.