After weeks of dry, sunny weather it rained hard last night. Now, at first light, here at Fewa Hotel on Pokhara’s lakeside, I’m sipping a cup of Mike’s bold organic coffee. Bits of fog hang like damp gauze from the trees, and the restaurant eaves drip quietly.

On this idyllic morning, I can see the great white dome and golden pinnacle of the 115-foot-high Shanti Stupa atop Ananda Hill, the forested ridge rising over 1,100 feet above the lake. That inspiring sight triggers memories of the first time I hiked there in 1992, when the Buddhist peace monument was still under construction. For decades,the project was highly contested politically, but devotees persevered and hailed its completion in 1999. (There is an identical Peace Stupa at Lumbini, Buddha’s birthplace in the Nepal Terai, and another 78 worldwide.)

On this idyllic morning, I can see the great white dome and golden pinnacle of the 115-foot-high Shanti Stupa atop Ananda Hill, the forested ridge rising over 1,100 feet above the lake. That inspiring sight triggers memories of the first time I hiked there in 1992, when the Buddhist peace monument was still under construction. For decades,the project was highly contested politically, but devotees persevered and hailed its completion in 1999. (There is an identical Peace Stupa at Lumbini, Buddha’s birthplace in the Nepal Terai, and another 78 worldwide.)

My daughter, Liesl, accompanied me that day as we climbed a (then) little-used trail from the lake’s southwest shore. The morning was partly cloudy, threatening rain. At the top, an architect’s sketch showed us how the huge stupa would eventually look.

Annapurna Himal dominates the panoramic view from the hilltop, with Machhapuchhre (‘Fishtail’ peak) out front standing guard over the broad valley. Below that, Lakeside Road winds along the northeast shore amidst hotels, restaurants, shops, and narrow alleys.

I remember strolling along a grassy path down there back in 1963 B.T. (before tourists), when the lakeside was no more than a lonely cow pasture. In those days the water was blue, before the tail end of an irrigation canal filled with glacial Seti River water was diverted into it. That silt laden water soon turned it a steely gray-green and threatened a productive fishery. While the irrigation water no longer debauches into the lake, the silty color remains. And, now, the lake is invested with invasive ‘jalakhumbi’ plants, which were introduced (it is said) by someone thinking they would add a touch of beauty. Instead, the rapidly spreading water hyacinths threaten to choke the life out of this freshwater ecosystem. The locals hold periodic plant removal campaigns, and the government promises to help with the purge.

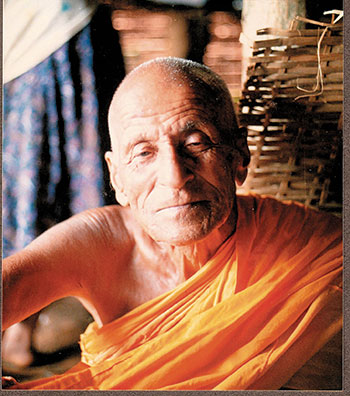

On that day atop Ananda Hill, Liesl and I met a happy little girl and a saffron-robed ascetic in a teashop. While we sat eating fresh sel-roti (rice flour donuts) with tea, the shopkeeper’s daughter smiled broadly at us over her snack, and the ascetic sat silently eating rice proffered by a local female devotee. The old monk was born a Hindu Brahmin in a village near Pokhara, but when he converted to Theravada Buddhism—an unforgiveable act in the eyes of his kinsmen—he became an outcaste. In time, he was widely revered as a Buddhist scholar, and recently, in his old age, he had retired to this hilltop. As we left the teashop, we gave him a polite salaam, and he, in return, recited a short blessing in Pali, the sacred language of Theravada Buddhism.

As we set off down a vague path through Rani Ban (‘Queen’s Forest’), it began to rain. We slipped and slid down a series of old terraces, once someone’s farm, now overgrown by trees. We lost our way a few times, but finally reached the bottom where we climbed over the back fence of Fishtail Lodge and entered the lounge to warm up and dry out. And there, to the utter disgust of a party of Indian tourists,we pulled leeches off our ankles and cremated them in an ashtray.

In retrospect, I’ll admit that killing those leeches was an unforgiveable act in disregard of the sanctity of Shanti Stupa high above us. It was further undeniably impolite of us to gleefully kill them in sight of lodge guests. Other memories of that day are far less tarnished, but all are indelible.

On second thought, it’s not only the inspiring view, but also the warming elixir of Mike’s coffee, that has triggered these musings in Spilled Ink.