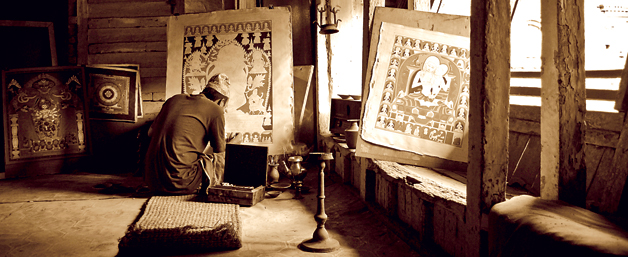

A Newar artist is sprawled in a room that is part-dim, part- bright; in short, a half light. The light comes through the ancient battered wooden windowpane, throwing itself on an embellished piece of canvas that looks as mysterious as it does dazzling. Mountains of colors and multiple hues and textures alight the deity depicted upon its surface. A flurry of poetry passes through the mind of the viewer of this extraordinarily striking piece of art as he hovers around the artist and his work. An ocean of lush, vivid, colorful tapestry is spread on a sheet of canvas, and here is an enigma - there is raw untamed passion to it. The artist knows that his masterpiece-to-be must be prepared accurately and with the utmost care as commissioned. If not, there is no benefit to his patron or to himself. He knows of the traditions involved, the characteristics that he should possess (and he does): modesty, religious temperament, sound senses and a kindly disposition of will. He does not consume meat, alcohol, onion or garlic and also adheres to the rules about personal cleanliness.

Tools of his trade

His preparations lay sprawled before him just like he too is sprawled on the floor, eyes gazing at every nook and corner of his piece with a precision akin to that of an eagle. There is no room for error. The tools he uses so gently yet with such tremendous effect are his brushes and paints; brushes and paints that will create an enigma. This is what he wants his art to be. His art shall lure eyes from all around him, and reflect images, colors and stories to the beholder. He niftily changes his brushes in his special box that has three holes especially dedicated to the three deities: Avalokiteshvara (deity of compassion), Vajrapani (deity of power) and Manjushri (deity of wisdom). His brush works as if moving on its own, a stroke here and a stroke there and then a stroke everywhere. The brush and colors move with an unstoppable speed and precision at an instance and then stops suddenly, and again he moves doing the reverse, contradicting the former method by being gentle and subtle with the art. While focused on his art, his mind is also meditating. Chants, doctrines, even simple words and minute suggestions recollected from his master’s teachings preoccupy his mind. He places an image of Manjushree in front of him and visualizes it dissolving into himself; he is now infinite in wisdom. The artist is also at one with his tools; visualizing the image that he is about to paint and the image itself dissipates into his instruments. The artist’s mind wanders around the suffering of different beings in different worlds and this masterpiece will benefit those who are suffering. His thanka is ready.

Water and light

It all started with the mythical beliefs of King Utayana’s artists, drawing the image of the Buddha from the latter’s reflection on water. This style came to be known as chulenma or ‘the image of the sage taken from water.’ Another story has it that a female herder in Kapilavastu was killed by a cow and was reborn as a princess in Sri Lanka, where she heard of the Buddha’s teachings. She took so much delight from these that she sent pearls along with a letter to the Buddha, and he replied by sending a letter back to her. Inside was a drawing in which an artist had outlined the rays of light surrounding the Buddha’s body. This style came to be known as ‘The image of the sage taken from the rays.’

Thanka painting is rooted in sophisticated religious Indian arts such as pata and mandala. Thankas are very popular in Tibet and Nepal. The Nepalese influence on the Tibetan painting has been consistent, pervasive and ultimately dominant, while the Indian influences have slowly faded away. What you see today on the busy streets of Thamel or Bhaktapur are Tibetan or Newari thankas, also known as pauvas.

The processes

Surendra Surav of the ‘Old Monastery Thanka Painting Art School’ in Jyatha (near Thamel) talks about the process of modern and commercial thanka writing .

For producing a thanka, the initiation begins with the making of a wooden skeletal frame. After this, a cotton canvas is prepared with a mixture of white clay powder, yak-skin and scalding hot water, which are all combined to create a thick syrupy solution that is spread by hand all over the canvas. Scraping is then done on both sides with some kind of plastic object (a useless credit card, for example). The product is dried in the sun from half an hour to an hour depending on the amount of sunlight it requires. A smooth stone is then rubbed over the canvas for a finishing touch and the cotton canvas is now ready for illustrating.

In the drawing process, light penciling is done: the image to be is outlined with a pencil. Water is spread over the canvas for permanency. Now comes the critical bold coloring is done around the penciled areas, followed by the shading process. There are three major types of shading used today: the tic-matrix, the dot-matrix and a final one that has no name. Three three brushes are used: a dark, light and a watered brush. Iconography is also done where measurements of the Buddha’s figure, face and image are taken. This is important for the different Buddhas have different physical features.

Lining is done at the natural and subtle areas of the illustrations, such as the hands and clouds. These linings and bordering are then colored for clarity.

The gold-painting process is applied. On grand expensive thankas, 24 carat gold is used and there are many rules and regulations to be followed here. Gold is usually used only at the important areas, but it is also used on other areas depending on the decoration and its practicality.

Later comes the facework, where the most crucial part of the thanka writing is performed, usually by a master artist. The expressions on the face have to be depicted very carefully. Balancing the parts of the face (eyes, nose, and mouth) is a very difficult process and an error made here is disastrous.

The final step to completion is the thanka mounting. Most thankas are mounted within a brocade frame, with silk brocade being the most popular due to religious reasons. Curtains are sometimes also added, both for protection and for enhancing the beauty of the religious art work.

The types of commercial thankas that sell most these days are figures of deities, The Wheel of Life and the Mandala. The Kalo Chakra Mandala designed by the Dalai Lama is one of the most popular and universally recognized mandala.

The differences in styles

Surendra Surav tells us that the difference between thanka and pauva (Newari thankas) is that thankas are made by Tibetans and people of Mongol ancestry, whereas pauvas are made exclusively by Newars. Where thankas depict Buddhism and its values and beliefs, pauvas depict a lot of Newar deities. The dress and pattern of the deities also differ. And while pauvas are extremely detailed, thankas are mostly not.

The artist, after the completion of his masterpiece, submits it to his patron in a bowing posture and is paid a lofty sum for it. He has a smile on his face- a smile reflecting complete self-satisfaction and he recalls his own ancestors who had been masters of this art (and he is one too now). The thanka is now gone and he stares at whatever is left behind on the floor- the paintbrushes, his special box and the scattered bits and pieces. He shall now wait until his next assignment.