Dr. Wegner & the Music School of Bhaktapur

The Kathmandu University School of Music is located in Bhaktapur, and getting there can be horrific. Traffic in all shapes and sizes crowding every foot of space. Foul-smelling fumes of carbon dioxide spurt like black tails out of the Tata trucks carrying sand and bricks to build more dwellings that will stretch the valley’s resources even further. And the growing number of military checkpoints stretches the journey like taffy being pulled. But, we’re finally there.

Paradise Found

Paradise Found

Voila! The Kathmandu University School of Music: A universe constructed of brick, wood, light, air, and sound. The tinkling wind chimes wash away the traffic’s grime. In the distance, the chords of a grand piano ripple through the birds’ song. Rhythms of exotic drums and horns punctuate the space. Your soul feels at home among the bustling colors of the flower-abundant garden. Groups of statues in various poses add to the religious nature of the setting. Music and gods: such good companions. The scent of jasmine in the air catches in the throat, making you want to sing. In fact, that’s what many of the students who come here are taught: vocal Indian classical music. The do-re-mi-fa-so-la-ti-do of western culture translated into the sa-re-ga-ma-pa-dha-ni-sa of the raga. It is said that to sing the perfect “sa” is a way of being connected to the cosmos.

A School is Born

The official opening of the School of Music was in August, 1996. It was inaugurated during a state visit by Dr. Roman Herzog, the then German Chancellor, in November of the same year. Kathmandu University itself began in 1991 and is the only one in South Asia (twinned with the School of Oriental and African Studies, in London) that offers full-fledged courses in Ethnomusicology (that is to say, the study of the music of a particular region, mainly outside the European art tradition) Students from an estimated 21 nations come here helping to fulfill the school’s vocation: “ To train competent musicians who can then document, preserve and work creatively with the endangered musical traditions of Nepal.” The curriculum, taught by about ten local and foreign teachers, includes piano, classical guitar, and musical instruments originating from Northern India, among them the tabla, sarangi and sarod. Students can obtain M.A. or B.A. degrees, or study by the semester. Bhaktapur is considered to be “the capital of the performing arts” and so this traditional farmer’s town, where most of the population dedicates itself to music, is an ideal laboratory for this experiment.

A Labor of Love

The school itself is housed in a renovated 19th century temple called the Shivalaya. The pagoda-like structure was constructed by the Dhaubhadel family in order to obtain religious merit. Shyam, one of its members, was asked what he thought about the modification from private dwelling to public institution. “I am so grateful to Dr. Wegner, (the dynamic German drummer, head of the Music Department, instrumental in founding K.U. Music School) for the transformation” he enthused. “Not only did he help keep my ancestral dwelling from falling into ruin, but he has also contributed enormously in keeping the Newari musical tradition alive.”

By any standards, the school is a labor of love and planning. From the library, computer and video room, permanent exhibition of musical instruments, to the digital sound recording studio, acclimatized sound archives, seminar room and three class-rooms, nothing seems to have been overlooked. The large garden’s centerpiece is an enchanting pavilion (mandap) decorated with wood-carved pillars. It is used for concerts, dance, and music lessons. The structure was designed and executed by the Austrian architect Goetz Hagmuller,

The gifted team has done a meticulous job. The principal renovator of the interior structure was Dr. Rohit K. Ranjitkar, Nepal Program Director of the Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust. Unassuming, he insists that the main job consisted of “reorientation” of the existing building. He notes that the basic construction was solid and very little structural changes had to be made other than reinforcing the roofs. Rohit adds, “The lieu is perfect for teaching the imperiled musical folklore of Nepal.”

Disappearing Sounds

The traditional Nepali music is as diversified as its estimated scores of castes, and each has its own melodies, rhythms and instruments. Unfortunately, much of this has disappeared. However, the Newars, especially those of the lower castes, happily continue to play their music during the many festivals and celebrations. The glorious past, that of the Malla Kings, from the 15th to 18th centuries, was the pinnacle of Nepal’s musical history. The rulers were poets; they played music, danced and fostered the growth of art as a way of life.

Gert-Mathias Wegner, the man most responsible for rescuing the Nepali sounds from certain oblivion, insists, “The musical traditions of Nepal are as diverse as the various ethnic groups of the country. Arguably the most complex musical culture in the Himalaya is that of the Newari people in the Kathmandu Valley, which in the course of the past 2000 years has absorbed mostly Indian influences shaping a unique musical tradition.”

Dr. Wegner’s own destiny is staunchly linked to India. As a student in the more pragmatic field of chemistry, a chance visit to Bombay in the Seventies gave his destiny an unexpected twist. He heard a genius play the tabla and became completely enamored. Played the egg-shaped two headed drums till his fingers bled. And then he played some more. Dedicated his energy into the sounds, not only of the classical piano (he’s a professional), but of all the nine drums in the Newari panoply.

A Conversation with Dr. Gert-Mathias Wegner

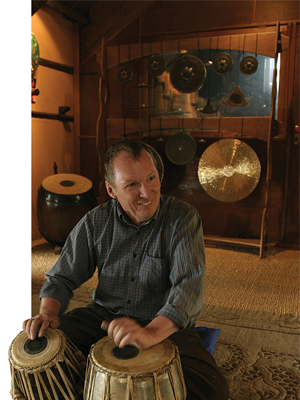

Seated cross-legged, at ease before his tabla, Gert-Mathias Wegner, appears strong, graceful. His hands move fluidly and from time to time an inner smile animates his deep blue regard. As an ethnomusicologist what is the difference between the cultural music of Bhaktapur and Kathmandu? “In Kathmandu, the Newars have become a mobile society. They don’t stay in the houses of their birth. They sell them. They move, intermarry between castes. In addition, there are so many other ethnic groups with different backgrounds. There is mobility within the hierarchy of the caste system. They forget about what each one would call my tradition. So then they create new traditions, (or none) and it becomes soft drinks and fast food. In Bhaktapur, this is not possible. People still conform to tradition. The town is built in the form of a mandala. In the center you have the palace and nearby, the most important temple. The higher castes live here. Then come the middle caste, the lower caste, and finally the outcaste at the outskirts. So your status is defined by where you live.”

Does the loss of certain traditions affect him? “Change is inevitable,” he states. Musing, “We also change, no?” For Gert Wegner, the Ethnomusicologist, this state of affairs must be welcomed. Pensively he says, “We recognize the fact that we are getting older when we say, oh it was so nice in my youth. The traditions were still alive and wasn’t it great… This is generational.” Asked, but weren’t the old days better? He thinks it over. “Nowadays global unification and intensive communication increases the speed of transformation. This can’t be prevented, but with the creation of the music school, perhaps we can bring about a beneficial influence on the quality of change.” Why did he begin this department? “I realized that all the knowledge of my teachers was only aural, learned by heart. When they died the knowledge was gone. So I wanted to prevent that loss by publishing a tabla repertoire complete with CDs. But you can’t preserve music in books. You have to teach it. There must be people who play the music, otherwise it’s useless.” How did he proceed to make his idea a reality? He touches the tabla in front of him. “First I started working with the Ministry of Education. It took four years. It was difficult and time consuming. We needed two cabinet decisions because development aid money was involved. In the beginning I worked with Tribhuvan University, but complications arose so I began negotiations with Kathmandu University. This required another Ministerial decision, he says smiling. But everyone was very helpful.”

How do you get students? “We advertise mainly in newspapers. Some foreigners want an M.A. in directed fieldwork as ethnomusicologists. For these studies you need an intellectual background and must know more about music than just playing two chords on a guitar. Unfortunately we don’t have enough Nepalese students. Music is not taught in Nepali schools so pop music is their only reference. One of our students was Nabin Bhatterai, a pop icon. Most of the young people who come here have the naïve idea of becoming a star like him. Unfortunately, the demand for such a talent is limited.” To parry this, the K.U. Music School has introduced a one-year diploma for Nepalese students including the study of language, anthropology and studio technology before they can enter the B.A. program. This prepares them for further studies such as digital sound recording. Gert states persuasively, “After all, what will they do with music in Nepal? Forget it! But if you know how to do professional recordings you might land a job with a radio or T.V. station.” The study of traditional music is complicated by social taboos. Certain drums can’t be touched by everyone. For example, not many would voluntarily learn to play a drum which belongs to the butcher or tailor’s caste. You would be ritually defiled. Dr Wegner exhorts, “That’s what foreigners can do—work with all these different castes, become familiar with all the instruments because those social conventions don’t apply to them. And even Nepalis can learn to play the Sarangi here, in a neutral setting, without being considered poor and of a low caste. Musicians generally belong to low castes.” Dr. Wegner hastens to leave. He’s due at the airport to meet a group of young German visitors to the school. West continues to meet East.

The Master Drummer and His Pupil

Back in the garden, Simonne, an English woman who received her B.A. in ethnomusicology a few years ago, introduces me to her guru, a farmer, an ex-stone cutter, the exceptional master drummer, Hari Govinda. She acts as translator. He is leader of the group, “Master Drummers of Nepal” (they have made a CD) and has performed several times in Europe. Simonne explains,” Hari plays all nine drums and of course the cymbals. He is considered to be the best because of the rapidity of his drumming and of the virtuoso bits that go with it.” When and where and with whom does he play? Hari replies, ticking off on his fingers the major festivals like Shivaratri, plus the fourth day of the Newari month. “About 24 times a year I play with fellow musicians from my neighborhood. All our music is religious. We play it for the gods.”

How does he feel while playing? “Happy. Especially when the music is complicated,” he smiles. And continues,” At Dashain when the special tunes are played I rejoice for a month. In my heart I play for my own pleasure.” He comes from a family of male musicians. However, in an unusual step, he is teaching his 22-year-old daughter to drum. Why? “Because I don’t have a son.” He is also training three boys who will one day take over from him. In Bhaktapur, there are about 60 musical groups. And every eight years there’s a training period for everybody who wants to learn singing, drumming or other instruments. About fifty years ago, Hari Govinda learned with a group of nine boys and he is the only one who “remembers.” Will he play much longer? Hari breaks into a broad grin and laughs, eyes flashing, “When I die, I’ll stop.”

Simonne plays some wind instruments and says about drumming, “I’ll never play well because I began after the age of 50. However I can play the virtuoso bits because I understand the structure of the music. My main interest was anthropology, not musical instruments. But since Dr. Wegner said it was compulsory to learn singing for two years I had to go along with it. I didn’t like Indian music even though everyone raved about it so I thought I’d give it a try. Gradually I got to like everything happening here.” How would she describe the music scene in Bhaktapur? “Vibrant. It’s happening all the time but with the older generation. Most of my friends are over 50. The younger folks like modern music.”

34,480 Ragas

Prabhu Raj Dhangal, a 34-year-old, curly haired vocal teacher, also has his own music school in Kathmandu, named after his father, once a singer at King Mahendra’s court. He advised his son never to become a singer because “financially it is very difficult in Nepal to survive by singing.” So Prabhu dutifully studied commerce, but never renounced his first love. In fact, he learned to sing on the sly, copying his father without the latter’s being aware. Eventually, at the age of seventeen, Prabhu revealed his secret. The older man was so impressed he decided to teach his son everything he knew.

So what does Prabhu like about singing? “It’s simply the best subject in the world. There are no limitations. When I’m happy I sing. When I’m sad I sing. I sing nine, ten hours a day because when I’m not teaching I want to improve my own skills.” Do you want your children to be musicians? “Yes. I have a five-year-old daughter. Her name is Suhanee.” He sings the notes in her name. Sounds like nostalgia. He volunteers,” This is the color of her raga. Each has a different shade. The total number of ragas is 34,480. It is very difficult to create new ones. A raga is a musical composition constructed with twelve notes. Songs for the evening and for the morning, each sung according to what you want to express. In Pakistan, even though they are not Hindu they sing ragas, only by a different name. The aural tradition and the ragas have not changed, only the taste of the audience has changed.” And Prabhu? Will he continue to sing even though money is scarce and the times are difficult? He smiles, “I will continue to sing because of that.”