Hendrix, Jagger, Marley and The Beatles are all said to have visited Nepal. Legend puts two of them at one inn in Jomsom.

Any celebrity who ventured today into a town like Jomsom, as both Jimi Hendrix and Mick Jagger are said to have done in years past, would find their photo posted on Facebook by a wireless trekker before the cappuccino got to the café table.

But in the semi-medieval mists of Nepal’s early trekking days, a famous visitor was like a two-headed calf or a yeti’s scalp. Someone’s friend might swear he’d seen one, but you couldn’t know for sure, and in time the stories were enshrined in guidebooks and local lore. There are tales of Cat Stevens on Freak Street, Bob Marley in Muktinath, the Beatles at the Kathmandu Guesthouse. The present has Twitter, but the past spun legends.

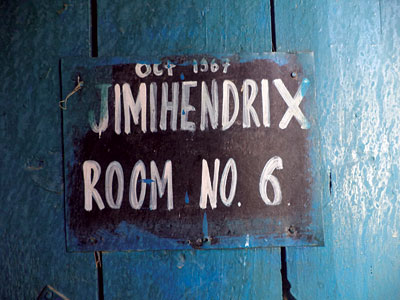

It was into this earlier version of Nepal that Jimi Hendrix is said to have stepped in 1967, following the hippie trail around the Annapurnas. Years later, Jagger supposedly honored Hendrix by staying in the same gritty lodge, where trekkers still leave colorful messages to add to graffiti signed “Jimi Hendrix Jomsom Oct. 67.”

It was into this earlier version of Nepal that Jimi Hendrix is said to have stepped in 1967, following the hippie trail around the Annapurnas. Years later, Jagger supposedly honored Hendrix by staying in the same gritty lodge, where trekkers still leave colorful messages to add to graffiti signed “Jimi Hendrix Jomsom Oct. 67.”

We hadn’t gone to Jomsom to look for the legend of Jimi and Mick. Like most people – including, presumably, any visiting stars – we were just passing through. Jomsom has a stark grey charm, like an Old Western town on the moon, but it tends to be a way station en route to somewhere else. Over 30,000 foreigners hike at least part of the Annapurna Circuit each year, along with pilgrims to Muktinath, and at some point everyone walks through Jomsom, mostly headed for the row of guesthouses marshaled like frontier saloons with their backs against a vast limestone cliff and their eyes on the tiny, wind-pummeled airport.

That airport is the only quick way in or out of the region, although the dirt road that carves an ugly if useful scar up the west side of the Annapurna Circuit carries most of the pilgrims and many of the backpackers. In case you’d like to drive it yourself, you can’t. It’s served only by public buses and jeeps that rattle dustily up what the BBC has dubbed one of the “world’s most dangerous roads” -- although this may only be because the BBC hasn’t seen many other roads in Nepal -- until they stop in the same part of Jomsom you’d find if you came by the 20-minute plane. That’s the end of the road. To go further, everyone has to shoulder their packs and file across a footbridge over the Kali Gandaki River to a jeep road that starts at the other, older end of town.

But as that part of town isn’t where most lodges are found, most people spend barely five minutes there, all of it in motion in a beeline to and from the jeep park. It takes a wrong turn or an oddball sense of curiosity to end up at the Thak Khola Lodge and Jimi Hendrix Restaurant 1967, whose sign announces, “Your chance to stay in the same lodge as Jimi Hendrix.” Squat and whitewashed, with a courtyard full of corn, the inn is a relic of a time when this area was unimaginably remote and accommodations weren’t just spartan – everything still is, even in the best of lodges – but threadbare, plastic-on-the-ceiling spartan.

Room Number 6 is the Hendrix Room, and to read the graffiti there is to connect with years of footsore, rock-loving, sketch-drawing, joke-cracking trekkers from Canada, Israel, Japan and who knows where else:

Room Number 6 is the Hendrix Room, and to read the graffiti there is to connect with years of footsore, rock-loving, sketch-drawing, joke-cracking trekkers from Canada, Israel, Japan and who knows where else:

We came from Thorung Phedi and over the pass / To check out this place where he rested his arse / We stayed for two days / It was a purple haze / Now we’re almost outa gear so we’re bailin’ – 1997

Came here looking for the spirit / only found this pain in my appendix / thought it was the apple cider / and the wind cried Mary - 1992

Did Jimi like the dal bhaat?

Time has passed it by, but in the 1960s, this inn may have been the fanciest in town. The air strip – it couldn’t yet be called an airport – was built in 1962 by the Red Cross to bring aid to Tibetan refugees in an outpost whose lodges catered to trader caravans, their herds of goats and mules loaded with salt to exchange further south for barley and rice. Tiny Jomsom wouldn’t even become the district headquarters of Mustang until 1975, so there would have been no one comparable to the reclusive clerk who now rents out the Mick Jagger Room by the month, his snores audible through the plank walls on which someone scrawled, “Mick Snores – Jimi.”

Guidebooks have long dubbed this trail an “apple pie trek” and Nepalis around the country know the glories of the famed Marpha apples, but a visitor in the 1960s wouldn’t have found any. The omnipresent apples (the Hendrix restaurant serves “apple fileter” and “apple pie and custanrd”) are due to Nepal’s own Johnny Appleseed, a man named Pasang Khambache Sherpa. He wasn’t a local; Mustang isn’t Sherpa land. But he was well-traveled, moving from his native Solu Khumbu to learn woodcarving at a monastery in Tibet and thence to Bhutan, traveling across the Himalayas with famed Tibetologist David Snellgrove, and heading to France to study fruit-growing before coming to Marpha. It was in his adopted village, a short walk from Jomsom and its cobbled lanes now filled with Thamel-style shops, that this Nepali Renaissance man established the first experimental apple orchards and spread them to the neighboring districts of Manang and Dolpo.

Whether or not 1967 brought a rock-n-roll pioneer to Jomsom, it brought one revolutionary force: Pasang Sherpa and his economy-changing apples. The trees were bearing rich fruit by 1980, when the Annapurna Circuit was in its infancy with a scant but then-impressive 6,000 backpackers a year. Locals who had migrated south for jobs returned to open lodges, most of which seemed to offer apple pie to the hungry trekkers, whose numbers by 1990 had climbed to 12,000.

The Hendix inn is managed these days by Sukmaya Thakali, who heard about Hendrix from her husband, the late Man Keshar Thakali. They weren’t married in 1967, so she doesn’t know much except that her husband (“a good man, but he drank”) told her his visitor “was very, very black.” On Jagger, she has this to report: “About 25 years ago, a man came. He was maybe 50 years old. He had a long, long face, hair down to here,” she pats her shoulders, “and later people said he was a famous musician. But I thought they were kidding.”

Could the tales be true? Well, 23 years ago, in November 1990, Jagger was indeed in Nepal. He was on his way to a Hindu wedding: his own. As it happens, it wasn’t his first link to the Himalayas. In 1968, Mick’s brother Chris was 20 years old and living near Swayambunath, where he got to know the monks, as he recalls by email. At one point Mick helped him out by wiring 50 pounds to Kathmandu, the rough equivalent of $1000 today, which would have gone a long way in an era of five-paisa coins and three-rupee-a-night hotel rooms.

In 1990, though, the rooms the Jagger entourage took at Kathmandu’s posh Shanker Hotel, a former palace, cost quite a bit more than Chris’s old hippie-trail digs. They were a party of at least seven: Jagger, his longtime partner Jerry Hall, their two children, a nanny, a tutor, and a personal assistant. They had 26 pieces of luggage between them. The trip ended in Bali with a Hindu wedding in Sanskrit, which may have been exotic but was later used to contest the marriage’s legality when Hall filed for divorce, since neither party was an actual Hindu.

As for the Nepal leg of the six-week pre-honeymoon trip, did Jagger fly to Jomsom? Various unconfirmed sources also place him at Tiger Tops in Chitwan, on the Royal Trek followed earlier by Prince Charles near Pokhara, and around Everest. His brother, himself a musician and writer who has penned music and articles about Tibet, thinks that Mick went trekking, but no one can confirm a stay by the entourage and their 26 suitcases at the Thak Khola Lodge.

If he did end up at the inn at some point, either as an unlikely guest or as a curious passerby, he’d have found that the legend’s centerpiece is a bit of graffiti: “If I don’t see you in this world, I’ll see you in the next. Don’t be late. Jimi Hendrix Jomsom Oct. ’67.” The phrase is a misquote of a line from Voodoo Child (Slight Return), the Hendrix classic that begins: “I stand up next to the mountain, and chop it down with the edge of my hand.” It was written in May 1968 and recorded that October, a full year after the date given on the wall.

At any rate, Hendrix couldn’t have taken the hippie trail to Jomsom, because it didn’t go there. Lower Mustang, which includes Jomsom, only opened to independent trekkers in 1977, when the airport was expanded and restrictions on Manang lifted to the east, making possible the three-week loop of the Annapurna Circuit. And in his 27 years, Hendrix never traveled further than Europe – except, perhaps, on the astral plane, where free-spirited backpackers undoubtedly enjoyed his company.

Nor do other rumors of ‘60s and ‘70s rockers check out: Not Janis Joplin or Bob Marley, whose brief lives are well-documented, and not even Cat Stevens. The future Yusuf Islam, who converted in 1977 and is active in Muslim-oriented social causes, penned a tune that mentions Kathmandu (as did Joplin, John Lennon and Bob Seger), but never hung out on Freak Street except in recorded form.

The Beatles were at a luxury ashram in the Indian foothills near Dehra Dun in early 1968, where they meditated and wrote Polythene Pam, Mean Mr. Mustard, and Back in the USSR. Bungalow Bill was inspired by the ashram’s bungalows and Americans who broke meditation to go on safari; Dear Prudence was an ode to a troubled fellow meditator, Mia Farrow’s sister. George Harrison became a Hindu and over the course of his life made pilgrimages to holy places, even bathing during his dying days in the sacred Ganges, where his ashes were scattered. (So were Jerry Garcia’s of the Grateful Dead, but he’d never visited the Subcontinent and the incident, his widow’s decision, was controversial.) Of course, it seems unlikely that an observant, wealthy Hindu like Harrison who kept an altar in his home and covered his walls with paintings of Ganesh, Laxmi and Krishna would never manage a pilgrimage to Pashupatinath or Muktinath, two of the most sacred sites in the Hindu world. But as for the Beatles, in spite of claims that the Fab Four stayed at the Kathmandu Guest House in 1968, no Beatles biography mentions a trip to Nepal.

That’s not to say the musically famous don’t drop by. Sting has made several trips, rafting down the Trishuli River with his wife and son, dodging photographers at Pashupatinath, and once joining an impromptu jam session at Jazz Upstairs in Lazimpat, ducking out only after word got out and the crowds poured in.

But lyrics, rumors and restaurants in a rocker’s name do not equal a visit. Perhaps it’s better to sing the praises of Nepal’s real stars: people like Pasang Khambache Sherpa, who in 1967, while Hendrix was performing a world away, was really in Jomsom, bringing apples to a grandly scenic but hardscrabble region and changing the lives of thousands of his neighbors. n