Sir Edmund Percival Hillary KG ONZ KBE was born in Auckland 100 years ago on 20 July, 1919, a New Zealand mountaineer, explorer and philanthropist who was hurtled into history on 29 May, 1953 when he and Tenzing Norgay became the first climbers to stand on the top of Mount Everest. With that last summit step, they broke altitude and endurance barriers, venturing beyond the known limits of human capability to the highest point on earth.

The memorable image of the expedition is Tenzing, bundled up, unrecognisable but triumphant on the summit. It was snapped by Ed who did not bother with one of himself, characteristically self-effacing in that moment of accomplishment that came to define his whole life. From a humble beekeeper in rural New Zealand, Ed had to reinvent himself as the hero conqueror of the world’s highest mountain, the news of which brightened a war-weary Britain on the morning of the young Queen Elizabeth’s coronation. His Knighthood was amongst the Queen’s first official announcements, made before Ed was even off the mountain.

The rest of his life was lived in the reflection of this single achievement, as the gracious kind-hearted Sir Ed, Knight of the Garter, the approachable Kiwi whose home number was listed in the Auckland telephone book. “It’s not the mountain we conquer, but ourselves,” he wrote. A national hero famed for his courage, but so painfully shy that he had to prevail upon his future wife Louise’s mother to ask her to marry him.

Hillary’s books were eloquent and even poetic, sharing with millions his love of challenge, stories of his adventures to mysterious Himalayan ranges, Indian rivers and Antarctic wilderness. He was the first person to reach both the North and South Poles and the summit of Everest. Sir Ed’s craggy features and distinctive profile squints into the distance on New Zealand’s five dollar bill, but his reaction was typically humorous and unassuming: “I thought you had to be dead or royal to get onto a banknote!”

But if Everest defined Sir Ed, he preferred to be remembered for giving back, investing his time and energy in the people whom he found struggling for survival in the shadow of Sagarmatha, and without whose help he could not have reached the top. The Sherpas led an uncertain life, as farmers scraping a living from the poor upland soil with their traditional trade with Tibet and occasional expedition work, at the mercy of external regional forces. It was only later that mountaineering, trekking and tourism brought fame and fortune, along with more reliable revenue. Sir Ed realised the necessity of education and health to enable his Sherpa friends to cope with impending change in an encroaching modern world, and to provide them with choices and alternatives. He dedicated the rest of his life to achieving this.

The story goes that in 1960 he asked the Sherpa elders: “If there was anything I could do for the Sherpa people, what do you think that would be?” The much-quoted reply was: “Our children have eyes but they are blind and cannot see. We would like you to open their eyes by building a school in our village.”

With his own hands and family helpers Sir Ed constructed a tin-clad shed that became the first classroom of Khumjung School, the ‘schoolhouse in the clouds.’ More do-it-yourself practical Kiwi buildings followed to house the region’s first clinics at Kunde and Phaplu. Several hundred porters were hired to carry supplies of shovels and pickaxes from Kathmandu bazaar along tortuous trails to the Khumbu. To support the schools and hospitals, he built the Lukla airstrip in 1964 on a steep hillside at 2,860 metres, mobilising teams of Sherpa dancers to flatten and compact the earth with their stomping steps. By his own admission, Sir Ed was surprised and rather alarmed by the tourism influx that he unwittingly prompted with the airport.

From these beginnings, personally hauling timber and hammering nails on annual visits between global fundraising trips, Sir Ed’s Himalayan Trust grew, enabling the entrepreneurial spirit of the Sherpas to emerge and flourish, their innate highland hospitality well suited for tourism. Over the decades, millions have benefited from the schools, hospitals, clinics, water supplies, nurseries, airfields and other facilities that the Himalayan Trust has contributed throughout Solukhumbu, and hundreds of thousands of Nepalis have received direct scholarships and subsidies since it was founded by Sir Ed and his wife Louise in the 1960s.

In a tragic accident on 31 March, 1975, Louise and their youngest daughter Belinda were killed in Kathmandu when their single-engine aircraft crashed on take off on their way to join Sir Ed and his brother Rex who were building the Phaplu hospital. Despite the devastation of his loss, he persisted with his charitable work on regular visits to Nepal. June Mulgrew, family friend and widow of climber and yeti-hunter Peter Mulgrew, helped him through the dark times following Louise’s shocking death.

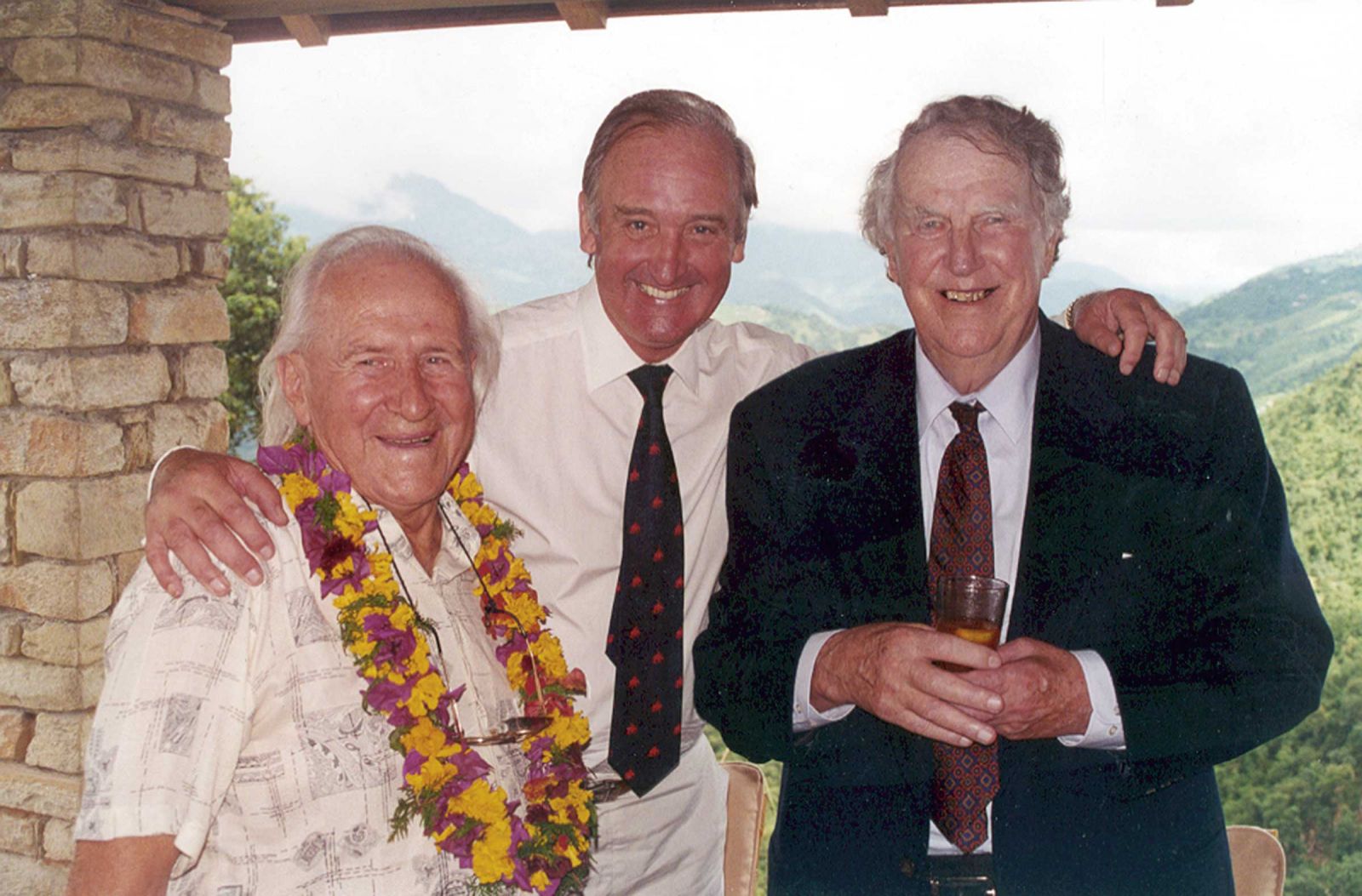

Ten years later, appointed as New Zealand High Commissioner to India and Ambassador to Nepal and Bangladesh, Sir Ed was able to broaden his influence beyond the Khumbu. June accompanied him for his four years living in New Delhi, and in 1989 they married on return to New Zealand, 14 years after the crash.

It is over a decade since Sir Ed’s death on 11 January, 2008, peacefully passing away in an Auckland bed, but his legacy proudly endures. His vision that the younger Nepali generation step up and take over his humanitarian work is evident, with responsibility for the Himalayan Trust Nepal now entirely shouldered by the Sherpa people themselves.

During his lifetime Sir Ed never sought personal accolades and resisted statues and named tributes in his memory. He preferred his actions and achievements to speak for themselves. It was only after he died that Lukla was renamed Tenzing-Hillary Airport and a statue erected at Khumjung, although he did agree to being ordained as a monk in Salleri monastery in 1999.

With five of his Sherpa colleagues and Elizabeth Hawley, his Kathmandu manager of the Himalayan Trust since its inception, I flew to Auckland for the rare State Funeral with which he was honoured; hundreds attended and it was broadcast around the globe. June was dazed but doing well. The house was full of flowers and family, and the doorbell and telephone never stopped ringing with more condoling friends and overseas guests, the great and good of mountaineering and polar exploration.

Life throughout New Zealand paused as the loss of their national hero was digested. Kiwi mourners waited in line for hours through the night to pay their last respects, his body lying in state with a military guard and medals displayed on navy velvet cushions. The rainy streets of Auckland were silent as Sir Ed was seen off in solemn ceremony, praised with a noisy Maori haka and acclaimed with an alpine sentinel of ice axes.

Sir Ed specified in his will that his ashes be sprinkled on the choppy waters of Auckland harbour, but Lady June had agreed to a special Sherpa request that some ashes of their beloved Burra Sahib be enshrined in a memorial chorten high on a ridge above Kunde, within sight of Mount Everest. Thus it was that I travelled back from the funeral with a navy velvet pouch of precious grey powder in my handbag, and a letter from the undertaker should I be challenged at any airport en route - which I was not. The package rested reverently wrapped in a kata on our mantelpiece beside the Dalai Lama shrine, until Ang Rita and the Himalayan Trust team were ready to take it to Lukla.

No Sherpas were with us when we boarded the stately Spirit of New Zealand ship to scatter the ashes one blustery afternoon in Auckland’s Basin Reserve. But Prime Minister Helen Clark was there, Lady June, Peter, Sarah and all the family with baskets of flowers, sombre faces and dark glasses. The date had been adjusted and delayed, dictated by the availability of the triple-masted sailing ship and the vagaries of the ministerial schedule. By auspicious coincidence it had fallen exactly on the traditionally important 49th day of Sir Ed’s passing.

We cast off from the waterfront into the bright harbour, and the officiating Dean’s robes billowed in the wind as I explained to him the significance of the auspicious Buddhist date. The Sherpas had expressed no surprise - of course, today is the proper day. The Dean was equally stolid in his faith, mentioning the 49th day in his blessing: “This is not chance.”

The weather and water sparkled but it was a sorrowful voyage, the final farewell scratchy with sadness. We returned to the Remuera house, forlorn despite the family bustle. Sir Ed’s big brown worn leather armchair was empty in the sitting room. Meanwhile the Sherpas were performing Buddhist rites for him in the mountains of Nepal that Sir Ed had loved so deeply.

This year, 2019, the centenary year of Sir Ed’s birth, is being remembered with events, books and celebrations throughout Nepal and New Zealand, including a recent visit to his Khumbu haunts by Helen Clark, in her capacity as the new Patron of the Himalayan Trust New Zealand. An old friend of the Hillary family, she had ensured New Zealand government contributions for the Himalayan Trust work in Nepal, and stood by June throughout the State Funeral in Auckland cathedral. At last month’s 29 May Sagarmatha Day reception in Kathmandu to honour his birth centenary, she said “Sir Edmund Hillary was without doubt our most distinguished and respected Kiwi of all time.”