The work of one of Nepal’s earliest professional photographers remains a vital link into the country’s history.

Watching Mukunda Shrestha’s photos is like opening a door into a Nepal I have never seen and never will. In fact, the photos are the only evidence of the existence of a time we can now only imagine: a clean Bagmati, a Kathmandu with mud houses and a Pokhara lakeside without buildings.

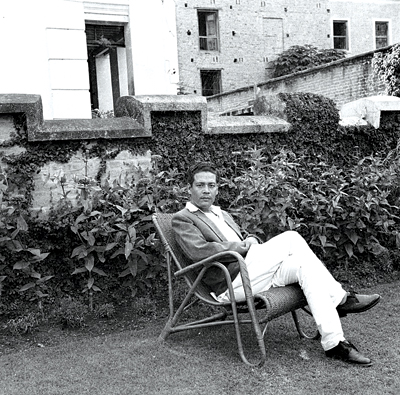

It is because of Shrestha, who was born in 1927, that people like me can get glimpses of the Nepal of his days. He began photographing as a child, using a box camera. His maternal uncle, Balram Bhakta Mathema, had a camera. Shrestha developed a passion for photography watching his uncle take photos. Sometimes, he would take his uncle’s camera without permission, take photos, and then surreptitiously put it back where it had been. When he was in his early twenties, Shrestha bought a couple of expensive cameras, once paying 500 rupees (an astronomical sum in the 1950s) for a German-made camera. Photography, however, was just a hobby.

It is because of Shrestha, who was born in 1927, that people like me can get glimpses of the Nepal of his days. He began photographing as a child, using a box camera. His maternal uncle, Balram Bhakta Mathema, had a camera. Shrestha developed a passion for photography watching his uncle take photos. Sometimes, he would take his uncle’s camera without permission, take photos, and then surreptitiously put it back where it had been. When he was in his early twenties, Shrestha bought a couple of expensive cameras, once paying 500 rupees (an astronomical sum in the 1950s) for a German-made camera. Photography, however, was just a hobby.

Shrestha’s maternal grandfather, Kaji Narayan Bhakta Mathema, was a powerful figure in the court of Chandra Sumsher, the Rana Prime Minister. It was this connection that landed Shrestha his first job. He was appointed supervisor of the foundry where jewelry and other products were fashioned for the ruling Rana family and their kin. His job came to an abrupt end when the place was robbed, and subsequently shut down. He soon found work at the Information Department. The agitation against the Rana regime was intense during this time, and Shrestha remembers seeing Ganesh Man Singh, one of the leaders of the anti-Rana movement, standing in shackles in a garden in Singha Durbar. “That would have been some picture,” he says. Photographing the renegade would, of course, have been out of the question; people were forbidden to even look at the chained man.

The Rana regime fell, and Shrestha was once again jobless. He found work as the manager of the Jan Sewa Hall, in New Road. But that job, too, didn’t last long as a fire destroyed the hall. This series of getting and then losing jobs culminated in the beginning of his hobby turning into a profession. In 1965, the then Tourism Department (now known as the Nepal Tourism Board) announced a vacancy for a photographer in the newspapers. Shrestha applied, and being the sole applicant, got the job. The first few years were uneventful. Shrestha was the staff photographer in an office that didn’t have a camera. There was no photography section.

Then, in 1967, Tirtha Raj Tuladhar, the Director of the Department, established a Photography Section. Shrestha was given a new camera. A career began that involved crisscrossing Nepal in search of photos. It lasted 23 years before Shrestha retired, having reached places that would change unrecognizably within his lifetime and seen things only few others would see after him. A few years after the establishment of the Photography Section, Shrestha set up a dark room—the only dark room at the time in Nepal not owned by a photo studio.

Then, in 1967, Tirtha Raj Tuladhar, the Director of the Department, established a Photography Section. Shrestha was given a new camera. A career began that involved crisscrossing Nepal in search of photos. It lasted 23 years before Shrestha retired, having reached places that would change unrecognizably within his lifetime and seen things only few others would see after him. A few years after the establishment of the Photography Section, Shrestha set up a dark room—the only dark room at the time in Nepal not owned by a photo studio.

The requirements of Shrestha’s job were like an official extension of his favorite hobby. He had always enjoyed visiting places. Growing up he had spent hours photographing in places like Pashupatinath, Swoyambhunath, Boudhanath and Godavari. As the staff photographer of the Tourism Department, he was going to be paid to do the same. This was a time when Nepal was known to the outside world as an otherworldly place, centuries behind the world, a true Shangri-La only a handful of outsiders had ever set foot on. The Tourism Department’s sole responsibility was to accentuate and propagate this mystical image of Nepal. Travel agencies, hotels, and foreigners alike were clamoring for photos that would prove that all the hype about Nepal was true. It was up to Shrestha to supply photographic evidence of Nepal’s beauty.

The dream job, however, had a few nightmarish episodes. There weren’t many roads in those days; all trips into the countryside involved several days, sometimes months, on the trails. Of all his trips, Shrestha remembers one most vividly. “The hair on my body still stands just remembering that place,” he says. He had been trekking with a German couple in the Langtang region for a few days when they arrived one morning at a bend on the trail. Turning the corner they found themselves separated from the trail by a narrow gorge a few feet wide. A plank of wood spanned it. The bottom of the gorge was not visible, but from somewhere way down they could hear the faint sound of a river. “We looked at each other, hoping that the other would go over first,” he remembers. They finally sent their porter first. Shrestha crossed over next. He collapsed on reaching the other side, drained by the experience. “My German companion slumped when he got across. His face was blue with horror,” Shrestha remem bers. On another occasion he had to cross a raging river on a bridge made from intertwined branches. People he’d met on the way had warned him that many people had fallen to their deaths from that rickety bridge. When the terrain was harmless, the desire to capture the perfect picture became the threat. During a trek to Gosainkunda he nearly fell off a cliff while absent-mindedly backing away to take a photo.

bers. On another occasion he had to cross a raging river on a bridge made from intertwined branches. People he’d met on the way had warned him that many people had fallen to their deaths from that rickety bridge. When the terrain was harmless, the desire to capture the perfect picture became the threat. During a trek to Gosainkunda he nearly fell off a cliff while absent-mindedly backing away to take a photo.

While out on assignment, Shrestha was given a daily allowance of five rupees for every kilometer he walked and another five rupees for food. That was good money in those days. But possessing money wasn’t always enough back then, especially when there was no place to buy. Trekking was usually a painful barter: In exchange for sights that sometimes lasted for mere moments Shrestha had to bear numerous hardships. “I once slept a few feet from a pigsty. On another occasion, I slept under strands of yak meat hanging from the roof. Sometimes, the rocks were our bed and pillow,” he says of his treks.

The days and months of travails on the trail resulted in sublime photos. The Tourism Department published several thousand copies of Shrestha’s photos as postcards and posters, which were either sent abroad directly or through the various embassies located in Kathmandu. In the period between 1970 to the late 1990s, Shrestha’s still images were taking Nepal around the world. Many of Nepal’s earliest tourists must have made plans to visit the country clutching postcards or gazing at posters of his photos.

Even as an increasing number of people began to see Shrestha’s work (some of his photos were made into postal stamps in Nepal), more and more of his photos were slipping into oblivion. After the best of his photos (according to the person selecting them) were selected, the rest of his photos, which formed the bulk of his collection, were stored away. A new rule had been introduced shortly after the establishment of the Photography Section that required it to produce a certain number of photos every year. Shrestha’s job was to achieve that figure. The minimum number of photos Shrestha was required to take annually varied from 3000 to 5000. For over 15 years Shrestha met the required quota of photos. Even by conservative estimates the number of his photos in the Nepal Tourism Board’s possession would be staggering. They lie, if they still remain, locked away in some storeroom owned by the Nepal Tourism Board.

Along with the Department’s camera Shrestha always took his personal camera on every trip and took thousands of photos with it. Nepal Picture Library, a photo archive setup by Photo Circle with the view to contributing to Nepali photography, has been working for over a year to create a digital archive of those photos. They have already archived 10,600 of Shrestha’s photos. Nepal Picture Library intends to eventually turn these and other similar collections into an online database, which will be available to academics, journalists, artists, photographers as well as the public.

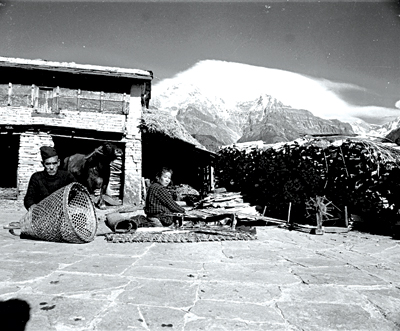

Being one of the first, if not the first, outdoors photographers in Nepal, Shrestha’s photos are a pictorial depiction of the multiple facets of Nepal’s past. Most of his photos depict something that has been lost forever. One photo I particularly liked (possibly one of his most widely seen photos, for thousands of postcards were made from it) is a scene from a village somewhere in the Annapurna region. A Gurung man and woman are working in their courtyard. The man is weaving a basket, the woman a blanket. Behind them a buffalo stands with its eyes closed in apparent bliss. A massive wall of ice and rock looms in the background. It is a simple scene, an image that could have occurred in any village near the mountains. People, animal, objects, and geographical features similar to those in that photo may still be around, but the harmony between them that the photo has captured is rarely seen nowadays.

Alban von Stockhausen, a Nepal-based anthropologist and photographer who has worked in the Himalayan Region for many years, has termed Shrestha’s early photos an “ethnographic treasure box.” He says, “Shrestha’s early black-and-white photos are not only aesthetically but also ethnographically of great importance. Through his very personal eye, we can experience the visuality of Nepalese life and how it changed over the years. In them can be seen tattoos of ethnic groups that have long vanished today as well as the expression of people listening to a portable radio for the first time.”

Shrestha’s photos not only give the impression to the viewer of time captured but of time stretched; centuries, not decades, seem to have lapsed since the photos were taken. And the man who took them feels the pangs of change more than anyone else. “I grew up in a Kathmandu of mud houses that had no terraces,” he recalls. He remembers seeking shelter from snowfall in a house near New Road and the devastation of the mega earthquake of 1933. And a Kathmandu that was sparsely populated. “If a man from Thamel came to New Road, he would stand out in a crowd. We would immediately know that he wasn’t from our locality.” Crowds in themselves were a rarity. “The only time there were crowds was during festivals.”

Taking photos for the Tourism Board meant Shrestha had to forfeit copyright. And the office was never keen on giving photo credits. The result was that although Shrestha’s photos went places, the man behind the photo always remained in the dark room. Recognition and accolades came slowly after he retired from the Tourism Department. In an international photo contest organized by the Asia-Pacific Cultural Center for UNESCO (ACCU) in 1998, Shrestha was awarded the Prize of the Photographic Society of Pakistan for his submission to the “Nature and Daily Life” category. In 2006, Shrestha’s photo of a young Sherpa woman porter, entitled ‘Himalayan Beauty,’ was among the two dozen photos selected for display at the 2nd International World Photo Exhibition. Shrestha is a recipient of the Golden Jubilee Medal Award, which was bestowed on him in 2002 during an international photo exhibition organized to commemorate 50 years of professional photography in Sri Lanka. The biggest irony has been that Shrestha has remained largely unknown in the country that he promoted so much through his photos. A significant step for him and his photos towards recognition came in 2007, when his photos were exhibited in the Patan Museum.

A single exhibition can hardly do any justice to the photos Shrestha has (leaving out those in the Nepal Tourism Board’s possession) amassed after working for over two decades as a professional photographer. It is unfortunate that the public has been deprived from a body of work of such value for so long. “I kept every single photo that I ever took,” he says. His vast collection was stowed away in bundles and albums in his house. He says that he himself had forgotten about them. “When the people from Photo Circle came and looked, they found some under my bed,” he said.

Shrestha traveled to all of Nepal’s 14 administrative zones in search of photos. His photographic journey spans different eras, from black-and-whites to color photos. When I first saw his photos on the computer in the Photo Circle office it felt like watching postcards that had somehow been lost and turned up decades later after being posted. My favorite is his photo of Pokhara’s Phewa Tal. Two girls sitting on a dugout canoe are paddling north. Between them is a bundle of firewood. Machapuchhrey and Annapurna thrust up from behind the hills like white fangs. The girl sitting in the back is looking back at the camera. I felt a sense of dual departure in the photo: The girls were heading home, but along with them time was also moving, pulling that way of life into the future, where it would have no place. Shrestha’s photo allows us a momentary eye contact with the girl, and through her, with the past.