This book is a breath of fresh air. Instead of long pages of exhortation or admonishment, there is a simple introduction, a few essays, and pictures. Lots and lots of pictures. We often read about the changes happening around the world, on the earth and our weather, but it’s perhaps harder to parse scientific facts and figures into something that impacts our daily lives, that we can use. By taking a simple premise—on being given an old box of photos, Alton C. Byers sets out to see if he can scrutinize landmarks, find exactly where they were taken, and take them again—something quite wonderful opens up. Instead of being told a thing, now we can see it for ourselves. I wanted to include something from Alton to go with the sample photos that I’m including here. The following, excerpted from the book itself, should get you going in the right direction. But don’t just take my word for it. This is a book worth reading, owning, coming back to, and an essential record that has documented changes happening in the Nepal Himalaya over the years, and now.

-Evangeline Neve

Khumbu Since 1950: Cultural, Climate, and Landscape Change in the Sagarmatha (Mt. Everest) National Park, Khumbu, Nepal

Excerpts from the introduction

by Alton C. Byers, Ph.D.

There is nothing permanent except change.

Heraclitus of Ephesus (c. 535 BC – 475 BC)

This book is a collection of historic and repeat photographs of the landscapes, forests, villages, glaciers, and people of the Mount Everest region of Nepal over the past 65 years. Most of the historic photographs were taken in the early 1950s by the first western explorers, climbers, scientists, and cartographers to the Khumbu region, which I have been replicating in the course of my work and research in the Khumbu over the past 30 years. In doing so, a fascinating collage of change emerges that has taken place in the interim, much of it good, some of it unanticipated and uncertain. The purpose of the book is to capture a record of this change that otherwise would be lost, especially for the younger generations of Sherpa people who, in spite of the Khumbu region’s relative remoteness, are growing up in a world far, far different than that of their parents and grandparents.

Over the past several decades, my career has taken me dozens of times to the Khumbu in search of answers to a constant stream of research questions, such as: how have forests and grasslands changed over the past several thousand years, five hundred years, and 50 years? Why were hillslopes and vegetation in the alpine zone so disturbed compared to the forests and shrub-grasslands below? What community-based methods could help to protect these fragile mountain ecosystems? How can the pressures of climbing, trekking, and adventure tourism be better managed, reduced, or eliminated? What were the impacts of climate change in this high mountain region? How quickly were the glaciers receding, and new glacial lakes forming? How could communities reduce the risk of glacial lake outburst floods? What were the impacts of the April, 2015 earthquake on the region’s glaciers and glacial lakes?

Insights to each of the above questions came from the dozens of research expeditions to the region that I’ve led over the years, some of which lasted a full year or more. Others were provided through a range of conservation, educational, and community development projects that I’ve had the privilege to lead or co-manage, generously funded by various donors that have included the National Geographic Society, National Science Foundation, U.S. Agency for International Development, American Alpine Club, International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, and United Nations University. Field methods have included geomorphic techniques to quantify soil erosion from hillslopes; pollen analysis and 14C dating of buried charcoal to reconstruct vegetation cover over the past 5,000 years; transects to determine groundcover in the alpine and types of disturbance; interviews and community consultations; bathymetry, ground penetrating radar, and discharge measurements of glacial lakes; remote sensing; tree ring analysis; vegetation analyses; fuelwood use measurements; and analyses of adventure tourism impacts on the trails, basecamps, and alpine ecosystems of the region’s trekking and larger climbing objectives.

Insights to each of the above questions came from the dozens of research expeditions to the region that I’ve led over the years, some of which lasted a full year or more. Others were provided through a range of conservation, educational, and community development projects that I’ve had the privilege to lead or co-manage, generously funded by various donors that have included the National Geographic Society, National Science Foundation, U.S. Agency for International Development, American Alpine Club, International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, and United Nations University. Field methods have included geomorphic techniques to quantify soil erosion from hillslopes; pollen analysis and 14C dating of buried charcoal to reconstruct vegetation cover over the past 5,000 years; transects to determine groundcover in the alpine and types of disturbance; interviews and community consultations; bathymetry, ground penetrating radar, and discharge measurements of glacial lakes; remote sensing; tree ring analysis; vegetation analyses; fuelwood use measurements; and analyses of adventure tourism impacts on the trails, basecamps, and alpine ecosystems of the region’s trekking and larger climbing objectives.

In nearly every case, repeat photography provided valuable additional insights to the more quantitative methods listed above. It can also provide an extremely effective educational tool that quickly and dramatically illustrates changes in glaciers, forest cover, and cultural landscapes over time.

In nearly every case, repeat photography provided valuable additional insights to the more quantitative methods listed above. It can also provide an extremely effective educational tool that quickly and dramatically illustrates changes in glaciers, forest cover, and cultural landscapes over time.

The technique itself is simple: find an older photograph, or series of photographs taken over a period of time of a landscape, glacier, or village. Find the precise photopoint used by the original photographer, and replicate the historic photograph as accurately as possible in terms of identical season, time of day, weather, and camera equipment (using identical lenses as the original photographer is hardly ever possible, but good substitutes can be made with modern equipment and Photoshop techniques). If what appear to be changes between the two photo pairs are apparent—e.g., changes in forest or ground cover—ground truth verification is critical to the most accurate understanding of events or processes leading up to that change, usually by establishing sampling plots in the area of question. Oral testimony from local residents can add tremendous insights to when, why, and how the changes occurred. Literature reviews, especially of older books written by the early scholars, climbers, and scientists to a region, can be an extremely valuable resource as well as a source of additional historic photographs. Time lapse satellite imagery and aerial photography can provide additional insights as to changes that have occurred, particularly with phenomena such as receding glaciers, growing glacial lakes, large-scale deforestation, and other large-scale features.

The older photographs that I used included, with permission, those of Namche Bazaar taken by Dr. Charles Houston in 1950, member of the first western group to visit the region in search of a southern route to Mt. Everest. Others include those of Sir John Hunt taken during the 1953 British Everest expedition; by Sir Charles Evans, Deputy Director of the 1953 British expedition; the Austrian climber-cartographer Erwin Schneider’s landscape and glacier panoramas from 1955, taken in the course of making the beautiful Alpenvereinskarte map of the Everest region; the Swiss-Canadian glaciologist Fritz Müller’s photographs of the Khumbu glacier and his Sherpa staff in 1956, following the successful 1956 Swiss Everest expedition; the Austrian geographer and alpine researcher Helmut Heuberger, a member of the successful Austrian Cho-Oyu expedition led by Herbert Tichy in 1954; the New Zealand forester Dr. Nick Ledgard, who since 1989 has assisted The Himalayan Trust and Sir Edmund Hillary Foundation of Canada in their reforestation projects in the Khumbu; New Zealand protected area specialist Bruce Jeffries; and mountain scientist-climber Rodney Garrard. Additionally, several of my own first photographs of the Khumbu region are now “historic” as they were taken in 1973 during my first visit to Nepal, and now provide valuable documentation of the tremendous change brought about from tourism and other factors since that time.

Because of their unique nature, it was tempting to include dozens and dozens of photo pairs within this book even if the changes in landscape or other feature were somewhat subtle. However, the final selection was usually governed by a set of criteria I developed that emphasized clarity and ability of the reader to detect change, be it vegetative, geomorphic, or cultural, mostly in the interests of ensuring enjoyment and the promotion of discussion.

As mentioned, most of the repeat photographs were taken from the same photopoint as used by the original photographers. It wasn’t that difficult finding the majority of the photopoints, especially since my guide, Pema Temba Sherpa, and other Sherpa friends met along the way were particularly knowledgeable about the Khumbu landscapes. But the precise location of some still remain a mystery because, try as I may, I just couldn’t find them. But just as popular passes, such as the Mingbo La from the Khumbu into the Hongu valley, become impassable because of avalanches and landslides, perhaps some of the original photopoints were destroyed by similar processes as well. Snow and safety conditions prevented the re-location of several others, as it just wasn’t worth the risk to carry on.

Although in most cases the locations of the photographs and names of mountains have been easy to identify, it was extremely difficult to identify the people from the ca. 1950s photographs. Most Sherpa did not possess cameras in the 1950s, and family photographic archives are generally scarce for this particular time period. Plus, 1950 was a long time ago, and many of the people shown in the old photographs, notably Fritz Müller’s staff who lived with him for nine months in the vicinity of Gorak Shep, are no longer alive.

It is my sincere hope that this book will be enjoyed by both Sherpa and Everest region aficionados alike, the latter including trekkers, climbers, scholars, and naturalists. It certainly has been fun creating, with each photo pair evoking fond memories of the hundreds of days and thousands of kilometers spent in the field retracing the footsteps of the early climbers, scientists, and explorers. In the interim, a new generation of professional Sherpa photographers and scientists has emerged; perhaps they will produce a sequel of this book using their own repeat photographs in the years to come.

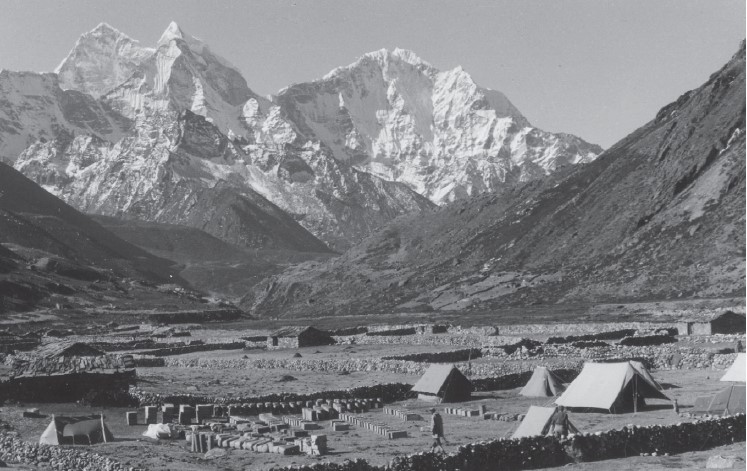

Another view of Pheriche in 1956 (photograph by F. Müller).

Another view of Pheriche in 1956 (photograph by F. Müller).

New, metal-roofed lodges can be seen in this 2007 photograph of Pheriche even from a distance. The river channel has expanded considerably, probably the result of glacier fl oods from the Khumbu glacier in 2002 and 2007, resulting in the loss of grazing lands. One of these floods destroyed the new concrete and steel bridge that the Khumbu Alpine Conservation Council (KACC) had built in 2006, but was replaced shortly afterwards. Note the loss of ice on the background peaks (photograph by A. Byers).

New, metal-roofed lodges can be seen in this 2007 photograph of Pheriche even from a distance. The river channel has expanded considerably, probably the result of glacier fl oods from the Khumbu glacier in 2002 and 2007, resulting in the loss of grazing lands. One of these floods destroyed the new concrete and steel bridge that the Khumbu Alpine Conservation Council (KACC) had built in 2006, but was replaced shortly afterwards. Note the loss of ice on the background peaks (photograph by A. Byers).

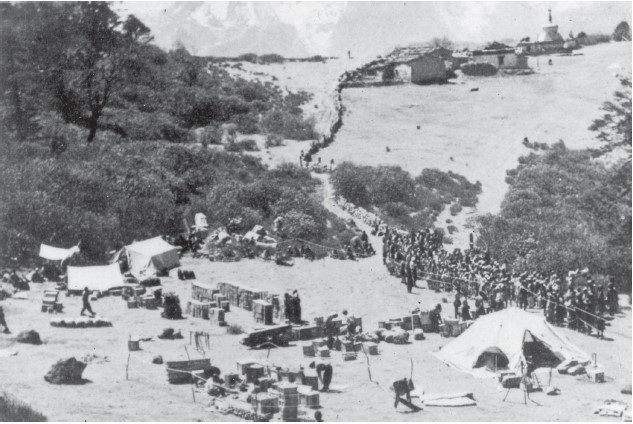

Looking east towards Everest from the Tengboche monastery in 1950 (photograph by C. Houston).

Looking east towards Everest from the Tengboche monastery in 1950 (photograph by C. Houston).

In 2013, at least fi ve hotels and a cultural center had been built in the same foreground region (photograph by A. Byers).

In 2013, at least fi ve hotels and a cultural center had been built in the same foreground region (photograph by A. Byers).