Heisenberg's uncertainty principle is an essential aspect of every trek in Nepal. Are we really going to Nepal? Will the flight take off? Will we be healthy? Will we change? What will we know?

Last October, friends from Amherst College class of ’76 decided to visit the country I’d called home since 1983. They were interested in where I’d gone, what I was doing and what it was about Nepal that attracted so many pilgrims.

Among my friends, Lee had first come to Nepal in October 1979, when a few of us spent two years post-college traveling the world. Within that larger journey, we took six weeks that fall to trek around the Annapurnas in the days before there were lodges along the Manang trail, only the porches of village homes to sleep on. We camped along a shepherd’s stone wall the night before crossing the never-ending 5,416 m pass at Thorong-La, before racing down the trail to the majestic barren landscape of Muktinath and on to traveler’s comforts in Thak Khola.

Gary, a community medicine doctor in Madison, Wisconsin, had visited me in Nepal during the ten year insurgency. His most vivid memory was not being able to return to Kathmandu from Pokhara because a group of young Maoists had stopped a public bus on a bridge near Kulinthar, forced all the passengers out on the road, and set it on fire.

For Peter, his wife Tarin, Bo and Holly, Cush, Lee’s wife Janet, and Brian, this was their first time in Nepal. Their professional and personal lives in the States as geologists, architects, doctors and freelancers had kept them occupied for the better part of four decades. The idea of Kathmandu had always been a dream too far. Many times we’d discussed them coming to experience Nepal, but during their own middle passage, they could never find the time to visit.

Retirement, however, opened up the corridors of time in a way that was never accessible earlier. In the fall of 2017, I’d stopped to visit Peter and Tarin in Albuquerque. Over dinner they took their Nepal trekking books off the shelf and, as we spoke, started taking detailed notes. I realized then that 40 years after I first came to Nepal, an Amherst ’76 trek to the Himalaya was beginning to unfold along the topographic maps on the table.

Dreams delayed are not always deferred. There comes a time when the demands of work begin to loosen and those romantic National Geographic images come back forcefully to mind. The stories that my friends had heard over decades of my life in Nepal had never quite receded, but merely lain dormant, waiting for the right time in their lives. Leaving Peter and Tarin’s home the next morning, I knew this 2018 Himalayan trek was on.

A year later, I stood at Tribhuvan Airport waiting for my friends to exit, watching carefully to see the reaction on their faces as they came outside amidst Kathmandu’s famous airport chaos. For each of them, there was simply joy, disorientation and a bit of awe. After the months of planning, they were here, far from the security of their homes, gazing north to the snow-capped Himalaya visible beyond.

Knowing these friends would want a guide who not only knew Nepal intimately, but could explain the intricacies of the traditional cultures and sacred religious beliefs they had come to explore, I’d asked Thomas Kelly, a long-term Nepal resident, photographer and friend to plan their trek, including adventure, challenges and spirituality.

Together, we planned a ten day trek from Phaphlu, along isolated ridges to the turquoise waters of Dudh Kund at 4,560 m just below the stark dominance of Nambar Himal. We would return by the Tubten Choling nunnery in Junbesi to spend some days attending the annual Mani Rimdu celebration at Chiwong Gompa, then back to Kathmandu.

As Thomas took these friends around Boudha, Pashupati, and Swayambu to give them a sense of the ancient spirit that animates the traditional cultures of Nepal, and for blessings from Tibetan monks, their practical questions revolved around the weather. Would our flight to Phalphlu actually go, do they ever go, or would we be driving ten hours into those hills instead?

No doubt, the Buddhist ideas of impermanence and equanimity jostled in their minds with concerns about an uncomfortable 4WD road trip nearly as long as their flights from the States. Some wondered if the first step on the noble path to overcoming suffering would be letting go of their fear of flying in the Himalaya and driving along its vertiginous mountain roads.

Fortunately, Nepalis are among the most patient and calm of people. Maybe that’s why these guides adjusted so easily to the uncertainties of our trek. For generations they’ve lived by the weather, farmers, traders, travelers all. When your homes are along the foothills and in the recesses of the majestic Himalaya, you accept the portents of the skies often rule your days.

So the next day, when the October skies hadn’t cleared yet and the roads were jammed with most of Kathmandu returning to their villages for Desain, we, too, merged into the Dhulikhel traffic for the long day’s journey to Phaphlu.

Yet, once the urban sprawl receded, the humble beauty of the middle hills spread out before my friends. The tawny ridges, aquamarine rivers and evergreen forests unfolded like an unexpected Cezanne landscape. We rode that thin line of bitumen steadily over bridges, then up along misty, cloud-covered ridges into the mountains of Solu Khumbu.

The next morning, as we started our climb above Phaphlu, past the new nurse training academy, below the pine trees, the conversations of contrasts began anew. The whys and hows of Nepali history and culture. The Western perspective on what is considered normal daily life and the stark differences in Nepal. The emotional and intellectual effort to untangle a wide range of thoughts on ambition, happiness, family and government.

A trek that demands much of one’s body, the exhausting effort to carry one’s 65 year old body up these steep ridges, can work as well to crack the mind and declutter one’s thoughts. The certainties of life are exposed to raw elements, as a harsh form of mountain meditation, with a fresh perspective stretching out to the distant horizon, as well as within the complex constructs of one’s thoughts.

We climb. We talk. We walk, We breath. We reflect. We wonder. We imagine.

Each morning, before breakfast, Tarin went outside quietly by herself to prepare her own sorcerer’s puja. Tarin’s a highly-skilled and experienced shaman of indigenous American traditions. She puffed on her sacred tobacco, said her prayers, made her offerings and thanked the universe for its generosity.

While over the breakfast table, Peter, Tarin’s husband, our PhD geologist-scientist now working on climate change in the Arctic, offered us his insights into the damage that our modern materialistic world is doing to the global environment and calmly warned us that the data he has seen is even worse than what we read in the newspapers.

But there is a time to talk and a time to walk. Miles to go before we rest. So, finished our meal, drank our coffee, laced our boots and stepped outside to stride beside the dzos carrying our bags led by the Sherpa, Tamang and Rai porters who appeared every morning to joyfully sing the world back into existence again.

As we walked, we spoke again of the contrasts, always the contrasts in Nepal. Our known realities of the Western worlds where most of us have spent our lives and the apparently remote uncertainties of this rugged Himalayan world. The unaccompanied, carefree children (calling out to us “chocolate?”) strolling purposefully past us to some unseen village while we well-equipped American trekkers prepared for most eventualities worried about the uncertain fate of the modern world we’ve created.

Surrounding us there is beauty and there is fear. The majesty of the mountains above us and the valleys below inspire awe at the natural world. The simplicity and lack of modernity in these isolated villages equally inspire awe at human survival and endurance. Yet, knowledge of the dangers that climate change and global warming pose to Nepal's world, and ours, was never far from our thoughts and conversations.

Anicca. Impermanence. These treks are opportunities to explore new worlds, observe traditional lives and challenge ourselves to gain a form of whole sight that is often obscured by the demands, obligations and ambitions of our busy individual lives. We know that, we think, but can rarely escape the fundamentals of our own lives.

Finally, we reached and slowly circumambulated Dudh Kund. A few Ruddy shelducks rested on the water. Behind them, the glaciers had receded, it was obvious to see. The moraines empty of the ice and snow that filled them a decade or two ago. The Himalayan scale stupendous, magnificent and yet deeply worrying. It was not possible not to see the rapid environmental changes in front of us.

Yet, after a week, still intoxicated by this elevation and isolation, it was time to head down to the valleys below. Antonioni’s wind-swept ridges barren of trees gave way to forests slowly being encroached for firewood and timber. The ragged sound of a jeep, or a motorcycle, drifted up as we walked down while an intimate part of us wanted to turn around, return to the distant, receding horizon, to that silence that had awakened our senses and liberated our minds.

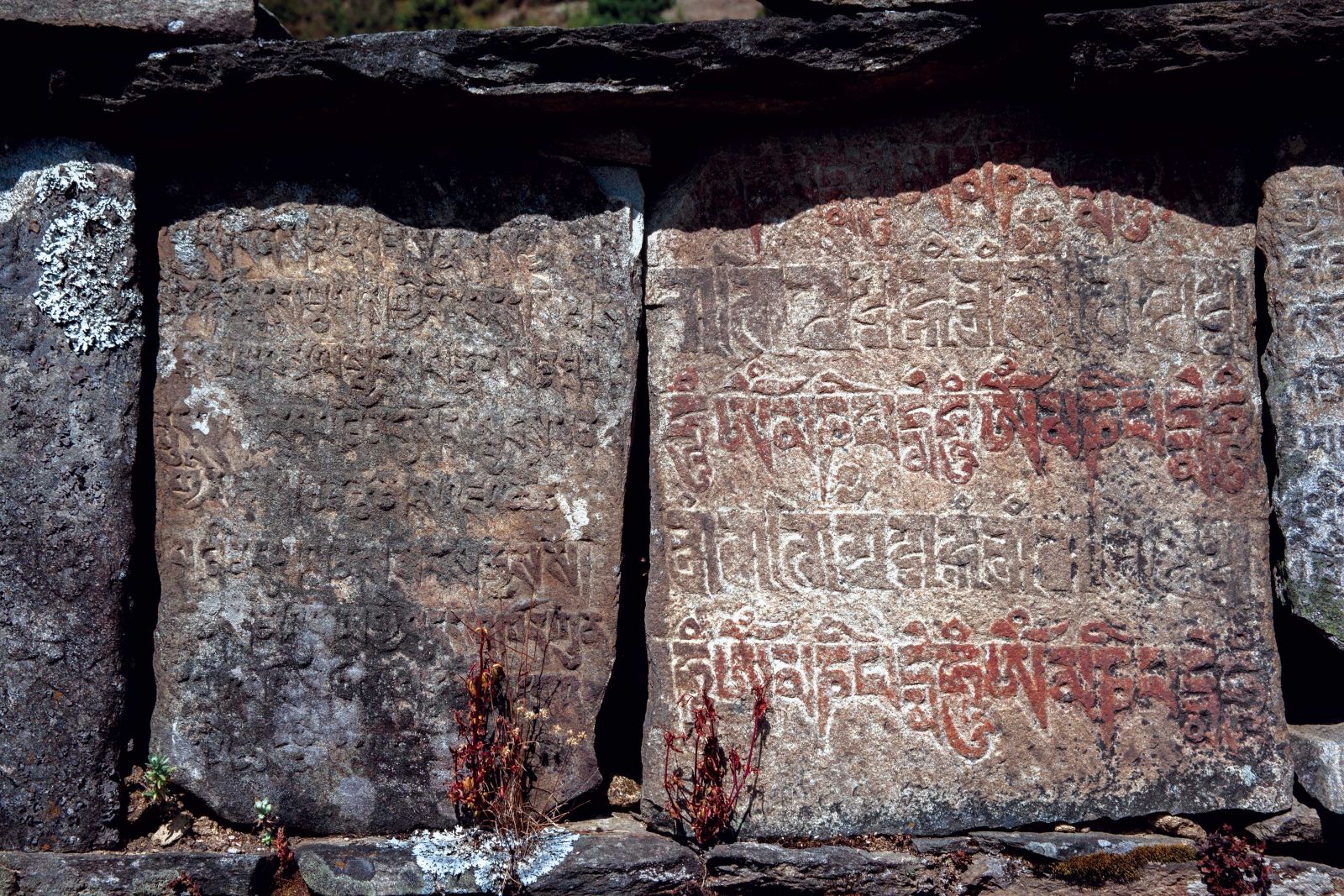

As reached Junbesi late in the day, we saw the impressive architecture of the Tubtencholing (‘the place of the Buddha’’s teaching’) monastery and the scurrying nuns in maroon robes hastening to the lakhang for prayers. The solitude we experienced while walking on those ridges ritualized in that Buddhist world. The sound of cymbals and drums aligned with subtle waves of guttural chanting filled the crepuscular evening air. The syncretized voices of the non-linear world surrounded and invited us in.

Culture. Religion. Sanctity. All the questions, the searching, the perplexities and doubts waned as sat in the large hallway facing the rows of shaven nuns chanting their dharmic prayers in unison, while an elder quietly strolled the aisles pouring hot butter tea for each of the novitiates, and us. We were welcomed with smiles and a slight laughter, these foreigners with their curious costumes and funny faces. We sat awkwardly crossing and recrossing our legs, clearing our minds and joined in the ethereal mediation of our inner realms.

Om. The sound of the unseen universe within. Om.

That evening, after dinner, we sat in the undecorated wooden dining hall next to the double rooms where we stayed. The conversation, naturally, returned to our individual experiences of these sacred and sanctified Buddhist realms. What do such non-visible worlds mean to each of us. To whom do we pray? From where do we draw our inspiration, our identity, our purpose? Is there a G-d or even a higher purpose to life’s creation? What do we hear when we listen in the mountains? Does our experience of Buddhism have answers our Judeo-Christian world doesn’t? Are there lessons we learn from each other? Do we fear death without a meaning?

In the blink of a trek, we have returned to our 18 year old selves in freshman seminars at college discussing the meaning of life, our origins, and the spiritual certainties that guide us. The Himalaya, the physical demands of trekking, the comforting sound of ritual, the monastic laughter, a release from our daily routines broke the congestion of our thoughts and allowed some diffuse light into those mysterious, invisible places. Together, these college friends have fallen into the amplitude of time where, once again, like awe-struck children, we wonder about the world in which we live without fear or shame.

We wonder, too, what have we gained? Knowledge? Insight? Knowingness? A taste spoon of wisdom? Are these, too, spiritual attributes of a trek into the wild places of Nepal? Does the travel literature promise, as well, that we can take home such gifts from what tourists called ‘an experience of a lifetime’?

Can these complex thoughts be packaged in rice paper or painted like a tangkha as souvenirs from the Himalaya to share with our friends and family in America? Did we, for a moment, reach Ronald Coleman’s fabled 1937 Lost Horizon, the mythic source of clarity, understanding and detachment?

Yet, for an evening among friends, if not for the length of a trek in Nepal, something did happen, maybe not revelation, nor an experience of nibbhana, nor whole sight completely, but, possibly, a return to the source, to an openness, to a momentary pause in judgement.

For ten days, these college roommates circled back to an earlier age of creativity that is usually the providence of the young. To a time of innocent questions, a whiff of wonder and a profound appreciation. Within the lasting mandala of friendship, where there is the urge to be closer, to share each other’s thoughts, to know each other and our selves slightly better.

To have gone deep into the Himalaya, returned, and felt blessed for having done so.

Keith D. Leslie has had a lengthy career in Nepal working for Save the Children, UNDP and the World Bank on issues of local governance, inclusion and community outreach. He has also raised a family of three grown children with his Nepali wife, Shakun, in their bamboo garden in Budhanilkantha.