Heads turn. People freeze in their tracks. Kids scamper up, chortling with delight. And as the hulking figure lumbers by majestically, you marvel at the creator of this living giant. An unusually bulky head, ears that reminds you of banana fronds, tusks like curved twin daggers, a nose that looks like a serpent, a body nothing short of a huge boulder, and legs like thick boles of a tree. There can be no mistaking this largest terrestrial creature living on earth: the Elephant.

Whether it is in a zoo, a theme park or a safari far out in the jungles of our Terai, the elephant lets you ride on its back…so docile, gentle and obedient, like a child. If you have visited Chitwan National Park, you must have had this experience: give some bananas to a park-owned elephant, and it gently tugs at your sleeve with its flailing trunk for some more, leaving you thrilled. One word, a nudge from the mahout, and it lowers itself down to its knees, lets you climb up its trunk onto its back, or performs such tricks as standing on its hind legs or folding its enormous forelegs in a show of respect. Whether it is performing amazing feats in a circus, playing polo, or even painting colorful pictures on an easel, this gargantuan ‘beast of burden’ has proven its mettle over the years. In defense, however, the matriarch wild elephant can turn into a fearsome adversary and is known to charge into a den of lions in Africa. Wild elephants are also identified as keystone species by naturalists, who help create an environment conducive to healthy ecosystems benefitting many other species.

Of all the wild animals in the world, elephants, or pachyderms as they are formally called, are said to be the most sensitive by nature. They play, cry, and…laugh, too. They are so susceptible that if a baby calf, the cynosure of the herd, whines, the entire family rushes over to touch and caress it. When a lost member reunites with the herd, it is greeted by every other elephant. They are said to have a legendary memory. They grieve, too, if a baby is stillborn, if any member of the herd is in distress, or at the loss of a family member. In other words, elephants are: “Beasts which passeth all others in wit and mind” – Aristotle.

An Icon

Elephant lore is plentiful. To followers of Hinduism, this creature identifies itself as the best known and the most widely worshipped deity in the Hindu pantheon, Ganesha or Ganpati (in India). Part human, part elephant, the son of Lord Shiva and Parvati, Ganesha is invoked by all as the icon of intellect and wisdom, a patron of arts, lord of success and sciences, and destroyer of evils and obstacles. The great Hindu epic, the Mahabharata, vividly relates great battles fought and won with elephants as war vehicles.

P laying soccer: An elephant positions the ball before attempting to shoot it past the goalkeeper

Shocking

My first encounter with wild elephants was at a place called Sainabar in Bardia district. I ran into a herd of 13 to 14 wild elephants foraging in the woods right next to the highway on my way back to Thakurdwara after a day’s fishing in the Babai River. As elephants are rarely seen in the wild, I was very excited at the prospect of taking some photos at such close quarters. I stopped my motorbike some 20 yards from the herd; but no sooner had I trained the camera on the herd when my guide Sitaram Choudhary, riding behind me, panicked. I lost my balance, and we nearly toppled over. “Sir, we better not stop here… It’s not safe. They can attack anytime, and if they do, we don’t stand the slimmest chance,” he blurted into my ears. I somehow managed some hurried shots before driving off. This short encounter, however, caused some commotion amidst the herd, for even as I kicked my motorbike into life, I caught a glimpse of one of the elephants turning sharply towards us.

Back at the lodge in Thakurdwara, my guide Sitaram unabashedly admitted that he was all set to abandon me and dash for the woods – the only safe thing to do when being chased by a wild elephant – had I dilly-dallied longer. For me, born and bred in the city, the revelation that elephants in the wild could be so dangerous, and could turn into a tool of destruction, or worse, cause human deaths, came as a total shock.

African vs. Asian

The word “elephant” that has its roots in Latin comes from two words: ele meaning arch and phant meaning huge. Of the many species of pre-historic elephants, only three genera are found today. They are the African elephant (Loxdonta Africana): the African Bush (also savannah) elephant (Loxodonta Africana africana), the African Forest elephant (Loxodonta Africana cyclotis), and the Asiatic elephant (Elephas maximus): the Indian elephant (Elephas maximus indicus), the Sri Lankan elephant (Elephas maximus maximus), and the Borneo pygmies (Elephas maximus borneensis). The oldest recorded elephant in the world lived for 82 years (shot in Angola in 1956), was the largest and weighed 12,000 kilograms (26,455 lbs), and was, 4.2 m (14 ft) tall at the shoulder.

A mature bull, Bardia National Park

Both Asiatic and African bulls are almost twice the size of their adult female partner. The gestation period for an Asiatic elephant is between 19 and 22 months (a little longer for the African). Both species breed at the age of 15 years and bear offspring (normally one) up to 50 years. Their life expectancy is very similar to humans – 60 to 70 years, or more.

Population

In the late 1930s, African elephants numbered nearly 10 million; dropped disastrously to 1.3 million in the late 1970s and to 600,000 in the late 1980s. Never abundant as their African cousins, and even more endangered, Asiatic elephants find their origin in the mammoth (mammuthus), now extinct. At the turn of the century, the population of the Asian elephant was estimated to be 200,000 (approx.). Today, there are fewer than 60,000 of which 38 to 53 thousand are found in the wild, 14 to 15 thousand are domesticated, and a thousand are scattered around zoos. Of the total population of Asiatic elephants, the Indian elephant makes up the bulk today, totaling around 35,000 (estimated).

Distribution

African bush elephants: Tropical rainforests of West and Central Africa. African savannah elephants: Eastern and southern Africa (Botswana, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Kenya, South Africa and Zambia).

Asiatic elephants: The Indian sub-continent (Nepal, India, Bhutan, and Bangladesh); continental Southeast Asia (China, Burma, Thailand, Laos, Kampuchea, Malaysia and Vietnam); and Asian islands (Andaman, Sri Lanka, Sumatra, and Borneo).

Behavior

Matriarchal by behavior, elephants, both African and Asiatic, live in a group of structural social order made up of mothers, daughters, sisters, and aunts. Such groups are led by the eldest females. Adult males mostly live solitary lives.

Status: endangered

IUCN’s Red List of mammals.

CITES: Appendix I & II

Human-Elephant Conflict

Shocking it is indeed when destruction and death caused by wild elephants make headlines. “Tuskers kill five in east Nepal”, “Wild elephants create havoc in Dang”, “Two trampled to death in Jhapa”, “Crops destroyed in Bardia” make news stories that are depressing and sad to read. But it is a brutal fact that every year during harvest time of corn and paddy, wild elephants in the east or west on the Nepal plains (Terai) go on the rampage. People lose their hard earned crops, livestock, property, and at times, even their lives. The reason for these sporadic outbreaks of savagery by wild elephants, however, is not difficult to find. In truth, they have been deprived of their natural habitat. The tuskers, who once freely roamed the abundant Terai forest, have had their habitat encroached upon and fragmented by humans. Farmers have laid claim to what was once their home turf. While it took eons for the pristine forests to take shape, human greed for more land has led to massive destruction of these jungles, forcing wild elephants now to trespass on human habitation.

On the Run

It has taken 400 million years for the planet Earth that we live on today to evolve. It has been an epic journey, tough and grueling, a formidable challenge for both man and creatures of Mother Nature. The biggest challenge for the animal kingdom, however, as always, has been man, the ‘thinking ape’ as he is sometimes referred to. If the evolutionary history of the early primates is to be dug up, the earliest known ancestors of modern-day elephants can be traced back to 65 million years ago, long before the birth of Homo sapiens in the Paleolithic Stone Age, 2.5 million years ago. Man came, and the ‘rape’ was on; untold species and numbers of our pre-historic elephants, the rightful early settlers of this planet, were pushed to extinction. Enjoying no more than a ‘refugee’ status today, always on the run, the impending doom for the wild elephants still lurks somewhere near the surface. And, it is one of life’s little ironies that the ones who were the cause of all the sufferings, worse, extinction of the earth’s rare inhabitants, are, today, supposed to referee the remedies!

“Elephant exist, even if represented now by only two or three of their 353 known species .They would seem to be on their way out, but it is still possible to argue that they represent the most highly evolved form of life on the planet. Compared to them, we are primitive, hanging on to a stubborn, unspecialized, five-fingered state, clever but destructive. They are models of refinement, nature’s archangels, the oldest and largest land mammals, touchstone to our imagination.” (Writer unknown)

“Elephant exist, even if represented now by only two or three of their 353 known species .They would seem to be on their way out, but it is still possible to argue that they represent the most highly evolved form of life on the planet. Compared to them, we are primitive, hanging on to a stubborn, unspecialized, five-fingered state, clever but destructive. They are models of refinement, nature’s archangels, the oldest and largest land mammals, touchstone to our imagination.” (Writer unknown)

Elephants (Elephas maximus indicus) in Nepal

The annals of history record elephants being used by the rulers of Nepal as far back as the Lichhavi Dynasty in the 5th century, during King Mandev’s reign. Trading of captured wild elephants by the early kings of Makawanpur to the Mughal rulers of India has been chronicled by the noted historian, Baburam Acharya. It is also common knowledge that domesticated elephants were widely used by the Ranas during their regime for big game hunting in the Terai forests. As recently as in 2009, geologists and sedimentologists from Japan and the Tribhuvan University discovered 40,000- and 24,000-year-old elephant foot prints, suggesting that the leviathans existed in the Kathmandu Valley tens of thousands years ago.

All-terrain vehicle… tourists enjoying elephant-back safari in Chitwan National Park

Distribution

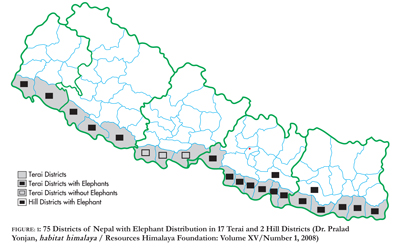

Of about 25% of Nepal’s total land area, or close to 36,360 km2 of forest cover (FAO figures), approximately 2,500 km2 of forest in the narrow lowland Terai belt, with 17 Terai and 2 Hill districts, are inhabited by wild elephants. Out of this, 1,600 km2 are under protected area management in the form of national parks and reserve forests, namely: a) Shuklaphanta Wildlife Reserve, 2) Bardia National Park, 3) Chitwan National Park, 4) Parsa Wildlife Reserve, and 4) Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve.

With diverse wildlife that includes endangered species like the Royal Bengal Tiger and the greater one-horned Rhinoceros, the narrow Terai belt that stretches across the Indian border along a 900-km stretch is also home to the wild Asiatic elephant. According to a survey conducted in 2001 by the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation (DNPWC), the wild elephant population in Nepal is estimated to be 91 to 127. Owing to lack of scientific monitoring, however, wildlife experts differ on these figures. It is also believed that this status falls under a transitional stage that affects their numbers, increase or decrease, as a result of mismanaged forests and loss of habitat. Their trans-boundary migration to and from India also influences the rise and fall in their numbers. Of the domesticated elephants, including government and privately owned, the number is estimated at 170 individuals.

Forage

Wild elephants in the Nepal Terai travel extensively on the look-out for habitat and food. Preference of food and habitat varies by the seasons. They prefer riverine forests, tall grassland and mixed hardwood forests during cool dry seasons (November-February), and short and tall grassland during hot dry seasons (March-June). Their main diet includes browse, bark and grass. They are classed as sympatric mega herbivores along with rhinos, which results in diet overlap over grass species between the two. If alluvial flood plains provide nutritious forage for them, sal hardwoods serve as mineral licks. Owing to their size (along with rhinos), they need more food and space than smaller ungulate herbivores like deer do. In the absence of natural predation, food in the dwindling forest landscape becomes the likely limiting resource for all these species.

With a rise in habitat fragmentation over the last few decades, elephants were restricted to splinter herds and were also compelled to take refuge in protected areas. The protected areas, however, are too small for long-term population persistence. This likely invites the risk of inbreeding depression, while extensive migration, both within the country or trans-border, is said to enhance genetic diversity. Primarily, the eastern, central, western and the far western parts of the Terai belt are home to wild Asian elephants.

Eastern Terai

With unspecified and unconfirmed numbers of resident elephants, the eastern Terai, during corn and paddy harvesting season, lures small migrating elephant herds (of 10-15 animals) from West Bengal, India. Herds reportedly enter Nepal by crossing the Mechi River in the vicinity of Bahundangi village in Jhapa district. Their movement proceeds by the contours of the Shivalik foothills to other districts like Sunsari and Saptari before retracing back to India after a brief sojourn. These herds are most vulnerable as the majority of forest paths along the Shivalik foothills have been either disastrously degraded or converted to agri-land and plantation. The dearth of habitat forces them to migrate back to India. Man-elephant conflicts, having dire consequences long since, has been a burning issue in the entire area.

Central Terai

Established and gazetted in 1984, Parsa Wildlife Reserve (PWR, area: 499 sq km), covering three districts (Parsa, Makawanpur and Bara), makes the largest wildlife reserve in the south-central Terai. Once exploited as hunting grounds by the Rana rulers, the reserve shelters herds of 20 to 25 resident wild elephants that stray off to the contiguous Chitwan National Park (CNP, area: 932 sq km), which serves as their dispersal area. As habitat requirement within PWR and CNP is adequate, herds stick to these protected forests. Although previously their home range extended to Bara and Rautahat until the 1990s, visits to these districts are only occasional now owing to escalating human pressure. Chitwan is also noted for an elephant breeding center established in 1986 at a place called Khorsor.

Western Terai

Western Terai

The western Terai boasts of the Bardia National Park (BNP), the country’s largest national park (area: 968 sq km) and the stronghold of wild elephants. The swathing Karnali floodplains and the lush Babai river valley record Nepal’s highest number of wild elephants. With almost 70% of forest being sal, BNP also abounds in riverine forests, shrub and grassland. Almost tipped at the brink of extinction in the early 1990s (only two elephants sighted in 1992), the year 1994 saw a sizeable colonization as herds migrated into Nepal from bordering India. “Once we witnessed from the Babai bridge a herd of as many as 32 elephants crossing the river,” “says Khadga Bahadur Khadka, a naturalist and hotelier from Thakurdwara, Bardia. The number shot up from 45 to 68 individuals believed to have entered Nepal on their migratory run via the three-km-long Khata biological corridor (located in the Terai Arc Landscape) linking BNP with the Katarniaghat Wildlife Reserve in India, and another trans-boundary natural corridor called the Basanta trail that runs along the foothills of the Shivalik and connects Shuklaphanta Wildlife Reserve, and the bordering Indian jungle. Surprisingly, the year also saw herds stay, and very little was reported by locals of their return migration. BNP also boasts of once having Raja Gaj, speculated as one of the biggest ‘bulls’ in Asia, who measured 11ft 3 inches in height at the shoulders. This giant pachyderm reportedly disappeared in the 1970s when it was 70 years old.

Far Western Terai

Pulling off a stunt

The far western plain of Nepal is noted for the Shuklaphanta Wildlife Reserve (305 sq km). Previously a hunting reserve, it was gazetted as a wildlife reserve to protect the last remaining herds of swamp deer. If the reserve is home to five to six resident elephants who alternate their residence to forest tracts of the Shivalik foothills in Kanchanpur district, some 11 to 13 individuals are said to be constantly migrating to and from bordering Dudhawa National Park, and Corbett National Park and as far away as Dehradun in northern India by crossing the Mahakali River. The forest along the Shivalik foothills, considered an ancient dispersal route, and once a contiguous forest tract that served for millennia as the ancient trans-boundary natural corridor linking Nepal to north and northeast India (the Basanta Trail), is allegedly encroached and fragmented. A recent news report in The Himalayan Times (Feb 2010) by Shivaraj Bhatta described heavy encroachment along this trail in Kailali by illegal settlers in the guise of flood victims, the landless and freed Kamaiyas (former bonded laborers), bringing in its wake massive stripping of forest cover. The report also read: “Three to five km of forest stretch is being ravaged every year, threatening the age-old natural corridors of their existence,” laments Tilak Dhakal, project head of the Terai Arc Landscape program.

Status

The status of wild elephants in Nepal is far from satisfactory. The National Park and Wildlife Conservation Act 1973 accorded them a protected status. Categorized as an endangered species by IUCN, the World Conservation Union under CITES lists them in Appendix I.

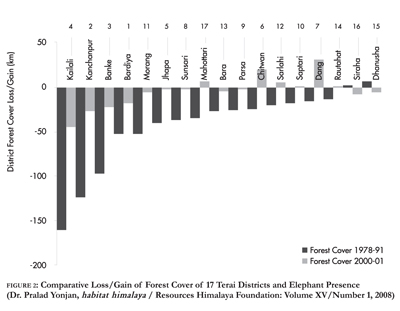

As with the entire Indian sub-continent, and continental Southeast Asia, the reasons behind the dramatic decline of Asiatic elephants in Nepal, too, are much the same. Human-elephant conflict has taken a nasty turn. If elephant raids end up in destruction of property, loss of livelihood and even human lives, elephants, in human retaliation, fall prey to poisoning, electrocuting and shooting. Habitat loss, depletion of forestland for human settlement and development work, hunting for ivory, illicit logging, excessive collection of fodder and firewood, and to some extent, capturing for domestication are the many causes. Nepal’s massive deforestation is said to have been brought about by the malaria eradication program in the 1950s, which also triggered a mass exodus of hill people to the fertile plains. This was followed by a Terai resettlement scheme in the 1960s, implementation of land reform program in 1979, and infrastructure development work like the Mechi-to-Mahakali Mahendra East-West Highway, all bringing in their wake massive destruction of forests. From 1950 to 1980, Nepal has lost almost half of its forest cover. Every year, lush primary forests are vanishing at a rate of 200 hectares a day (1.7% annually in the Terai plains), precipitating grave ecological and climatic changes. Also a matter of great concern to the naturalists, in 2006, 120 elephants in captivity in Chitwan tested positive for tuberculosis with possibility of the disease spreading to the already-threatened wild herds.

Towards Conservation

A cause of grave concern for all, the conservation issue of wild elephants in Nepal, besides being handled by the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation (DNPWC), has been lobbied by many wildlife agencies and NGOs. Stakeholders have made all-out efforts to save the elephants by implementing advocacy programs, timely addressing of habitat loss, and finding solutions to mitigating the worsening human-elephant conflict, which has risen at an alarming rate. Worst hit are the villages and buffer zones (the immediate areas inhabited by humans surrounding the national parks and reserves).

Resources Himalaya, Wildlife Conservation Nepal, Asian Rhino, Elephant Action Strategy, and WWF Nepal with their multi-faceted conservation programs, including the Terai Arc Landscape program, are the key agencies, who have made notable contributions in this regard. Granted, extensive conservation campaigns have been launched to the cause of maintaining a sustainable human-elephant relation, the threats to a healthy co-existence, however, will remain unless and until the existing forest cover is spared and replenished.

Simply put, the issue of the Asiatic wild elephants and their survival urgently calls for timely addressing and mitigation if we are to save one of the marvels of our planet – in reality, the last vestiges of the world’s pre-historic hairy mammoths from turning into lifeless stony fossils like their extinct ancestors.

The author is a freelance writer and outdoorsman. He can be contacted at ravimansingh@hotmail.com. The information and data for this article have been drawn from the works of Dr. Narendra Babu Pradhan, Petra F. ten Velde Thaguna, Dr. Pralad Yonjan, bulletins of the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation, and the Internet. The quotation that begins “Elephants exist, even if …” is borrowed from elephantcountryweb.com