Over time, and a number of earthquakes,

Patan has gathered a residential sprawl that is reflective of various years in history.

Four personal endeavors to preserve some essence of that unique history in their homes are prompting an appreciation for the old. The ‘traditional’ is catching up as the trending new.

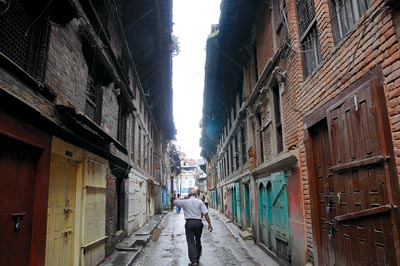

With the mesh of the handicraft and other shops that line the alleys around Patan Durbar Square paired with the constrained width of these lanes, you don’t really have a reason to go beyond your line of sight and look up. When you do look up, you see narrow vertical strips of designs reflecting architectural styles from different points in time. It’s the same even in various residential courtyards – a number of slightly different looking houses are stitched along quadrangles. Unlike public spaces and monuments that were built to reflect a particular reign or dynasty, the urban residential sprawl continued to grow with various influences from the medieval years onwards. Rather than interrupting the authenticity of the city’s true medieval character, the variety ensures this isn’t a space frozen in one particular age, or even a few dominant eras for that matter.

.jpg) However, since most of these structures are still privately owned residences, and have been lived in for years, the damage goes beyond the wear and tear of time. Down the generations, vertical division of buildings has ensured shrinking properties. Such socio-economic aspects have expedited the demolition of old houses. The traditional looking houses are fast being replaced by cemented conveniences. Conservationists are concerned about the pace at which this historic urban space is losing an architectural variety accumulated over history.

However, since most of these structures are still privately owned residences, and have been lived in for years, the damage goes beyond the wear and tear of time. Down the generations, vertical division of buildings has ensured shrinking properties. Such socio-economic aspects have expedited the demolition of old houses. The traditional looking houses are fast being replaced by cemented conveniences. Conservationists are concerned about the pace at which this historic urban space is losing an architectural variety accumulated over history.

GRANT AND ABET

Stand on one of the dabalis in the Durbar Square and look towards the Maharani Pokhari. You’ll spot a small, old house sandwiched between two newer looking buildings across the road. It stands in ruins with a blue sheet of plastic flopped over the beams that once upheld the roof. The sight displays the fact, that conservation efforts in the capital haven’t really moved beyond monuments and public spaces. The heritage site laws only protect structures that are more than a 100 years old and so don’t help the cause of many of these houses that reflect relatively recent times.

Around 1999, UNESCO grants through the Patan Tourism Development Organization (PTDO) put into momentum a rotating fund to encourage renovation projects among these residential buildings. These funds brought forth some successful ventures. Newa Chhen, a ‘traditional home’ bed and breakfast was restored for adaptive reuse with this grant. A beautiful Newar house with a large courtyard, this project was an example that renovated homes could not only be a way to keep your house intact, but also turn it into a lucrative enterprise. Rajbhandari House is another renovation project that currently hosts only commercial undertakings.

The idea was that despite it being a grant in essence, if the projects would gradually pay back the PTDO, they could loan out the money to other such residence owners. Devendra Shrestha, one of the owners of the Newa Chhen family venture, shares that aside from the grant, they had to take loans to complete the project as it exceeded their estimate. Add to that the expenditure on the new house they had to build to put aside the old section as the ‘traditional home’ bed and breakfast. It wasn’t until 2006 that the project was completed and it began as a hospitality venture. Rajbhandari house has a similar story as well. And so, the money is still in the process of being returned to the trust and the grant could not be circulated.

The fact that the fund did not end up rotating might have actually worked in the favor of the cause. The renovation of these houses has been taken up in personal capacities, and personal initiative is indicative of an outlook picking up momentum.

.jpg) THE CONSERVATIVE TALE

THE CONSERVATIVE TALE

“I am a crazy conservationist that’s why I have a home like this and that’s why I never tire of convincing others to renovate their homes as well.” Dr. Rohit Ranjitkar, a conservation architect is originally a resident of Kathmandu Durbar Square area. He bought an old house, a five-minutes walk from the Patan Durbar Square some 10 years back and has converted it into a traditional haven. He has broken all the stereotypes that come with old homes – narrow, dark houses with low ceilings and constant need for maintenance. “You can adapt the space in an old house to your needs with just a couple of adjustments. You can create bigger windows to brighten up rooms, reduce the use of bulky furnishings that break the flow of space, etcetera.” He has replaced walls and small doors with wooden columns and beams to create a sense of sprawling space, and mud floors have been replaced by wooden panels to reduce maintenance hassles.

.jpg) I asked him about one issue that invariably crops up if you know someone resides in an old house – the earthquake scenario. “Of course lives of people are of greater value than heritage conservation, but with current construction customs, there is no guarantee as far as safety standards go. The structural engineer’s design has become a mere formality to get official approval, and is hardly followed through by the contractors who cut down on costs at every level.” Ranjitkar insists that thick mud mortar walls are more flexible than thin concrete walls, so unless the standards are followed through, old houses are a safer bet as far as the earthquake scenario goes. He has reinforced every floor with diagonal steel strips as a safety measure.

I asked him about one issue that invariably crops up if you know someone resides in an old house – the earthquake scenario. “Of course lives of people are of greater value than heritage conservation, but with current construction customs, there is no guarantee as far as safety standards go. The structural engineer’s design has become a mere formality to get official approval, and is hardly followed through by the contractors who cut down on costs at every level.” Ranjitkar insists that thick mud mortar walls are more flexible than thin concrete walls, so unless the standards are followed through, old houses are a safer bet as far as the earthquake scenario goes. He has reinforced every floor with diagonal steel strips as a safety measure.

In most cases restoration is cheaper than building a house from scratch, but people have the perception that it is too much of a hassle and prefer concrete structures, Ranjitkar shared. “I like the warm feel of old houses, that’s why I chose to renovate and live in this house. This is home for me, so the priority during the renovation and furnishing process was convenience. I’ve used required amenities efficiently to make this house as comfortable as any modern structure.” The house is a reflection of Ranjitkar himself – his passion for conservation blending smoothly with the dexterity of an architect.

THE CONTEMPORARY DESIGNER

A portion of Jitendra Shrestha’s house is what remains of the west wing of a Malla period palace complex. Living in a house that old meant many inconveniences for the entire Shrestha family: the kitchen tucked away somewhere on the first floor with the water source being a well, many small and dingy rooms, and high maintenance costs. Shrestha decided to renovate and rebuild a portion of the house almost 12 years ago. This was an opportunity for him to make a convenient home while also adding a few accommodations that he could lease out to generate revenue, but he wanted to keep the traditional feel intact. However, the endeavor did something more important—it brought out his skills in designing, visualizing and effectively using his keen sense for space utilization.

.jpg) With no formal training in design or architecture, Shrestha says most of what he plans out for structures and space is out of common sense. The rest he just seems to have a knack for. He called his first restoration project Yata Chhen which not only functions as his residence but also accommodates three studio apartments that he leases out. He went on to work on eight other renovation and ‘traditional home’ projects over the years. He chalks out what he visualizes for structures on Google’s free Sketchup software or works out the basics on AutoCAD, and the interior is all about smart and convenient use of space. He has even moved beyond restoration and designed some contemporary houses for his clients.

With no formal training in design or architecture, Shrestha says most of what he plans out for structures and space is out of common sense. The rest he just seems to have a knack for. He called his first restoration project Yata Chhen which not only functions as his residence but also accommodates three studio apartments that he leases out. He went on to work on eight other renovation and ‘traditional home’ projects over the years. He chalks out what he visualizes for structures on Google’s free Sketchup software or works out the basics on AutoCAD, and the interior is all about smart and convenient use of space. He has even moved beyond restoration and designed some contemporary houses for his clients.

For Shrestha it isn’t about taking people back in time. He articulated, “Contemporary ideas have to be amalgamated to be able to use space well, better the feel, and work around old elements that stand redundant.” Yata Chhen has a ‘heritage’ feel because of the structure, but has well equipped contemporary looking studio apartment concepts. These accommodations are smartly utilized spaces peppered with Newari and Japanese decorative elements, and a common living room on the ground floor that everyone can share. The pride with which he showed me around made it clear that this was a personal achievement – a success story that gave him direction and a satisfying profession that he is carrying out efficiently. His newest project involves a restoration in the vicinity – an old friend’s dilapidated house.

.jpg) NEW TO THE CLUB

NEW TO THE CLUB

“I was ready to sell the property when Jitendra elaborated on the possibilities I could explore after renovating it. After seeing Jitendra’s house and a couple of discussions, I decided on restoring the house to have accommodations that I can lease out. After all, I grew up in this house; if there’s another option to selling it or tearing it down, there’s no doubt I’ll take the opportunity.” Prakash Dhakhwa has an old house that the family moved out of to live more comfortably. “The house is old, and hardly gets any light. The cold made it quite uncomfortable for my aged parents as well.” Dhakwa himself moved to Bouddha to explore some work opportunities and started working in a hotel. Now he works with handicrafts and also organizes mountain bike tours. He has taken a loan to renovate the house and sees this project as an important investment. He is confident that his venture will succeed.

I asked him why he hadn’t thought of renovating it before. “Earlier I wasn’t sure how to go about it. But I’ve seen Jitendra work on numerous projects and he has a lot of experience. I trust his judgment and I know I will get the returns we have estimated, else I wouldn’t have gone ahead and taken a loan.” He said he’s actually glad he hadn’t renovated the house earlier. “With little knowledge of what can be done, the house would have ended up looking like that,” he said, pointing at a neighboring house that has an imitated traditional feel created on the façade while the side walls are all flatly cemented. “Neighbors are inquisitive. They say they’ve heard that if old houses are renovated well, the value goes up. They are waiting to see how we fare so they can decide what to do.” I asked him how he is so certain that the investment will pay off. He said, “Yata Chen has been doing well for so many years. And look at how well Swotha Chhen is doing in a span of less than a year!”

.jpg) THE INSTANT STAR

THE INSTANT STAR

Six people from varied professional backgrounds came together to invest in the adaptive restoration of a traditional Newari residence to be used as a bed and breakfast—Swotha. Pawan Tuladhar and Deepak Upreti are into travel tourism, Shagun Pradhan is a restaurateur, and Abinash Pradhan is a Chartered Accountant. Architect Prabal Thapa, who was involved in the restoration of Kaiser Mahal (Garden of Dreams), and Jitendra Shrestha are also involved in Swotha. One look at the execution of this project and you get a feeling that the investors had a very clear idea about what they wanted to do with this venture, and the expertise in the varied fields seem to have worked in the project’s favor.

Swotha isn’t the typical traditional conservation effort. It seems to have been executed with an appreciation of the building and for the time it stands for, instead of giving it a medieval makeover. It’s visible the moment you enter the house as some characteristic elements are left as it is. The cement floor looks irregular, “The house is roughly 70 years old, but the floor must have been renovated some 15-20 years back and the workmanship is a little rough. We haven’t given it an ancient-wash to look the part, just made adjustments to accommodate amenities and use the space well. And, that’s actually what we’re being appreciated for.” Shrestha shares. Sukul or straw mats carpet the floor in large patches, and the narrow wooden steps that take you up to the various floors impart a ‘traditional’ vibe. But the seven rooms with attached baths are modern luxury accommodations. Complete with amenities, the rooms are tastefully done.

Managed by Cammile Hanesse (who Shrestha gives all the credit for breathing tasteful aesthetics into the house), Swotha has created quite a buzz in a span of just 10 months. Search for ‘traditional houses Nepal’ on google, and the second result is Swotha’s TripAdvisor review. It has 21 reviews with 19 ‘excellent’ ratings, and is ranked number one among 12 bed and breakfasts, and inns in Patan. With word of mouth complementing the accommodation, locals, visiting tourists, and even ‘potential’ tourists still planning the trip have heard of the traditional home. The entire venture is reflective of the nature of the investors who have taken an unconventional approach here. Their exposure and outlook is tangible in the way the Swotha project has turned out and in the way it is currently operating.

Managed by Cammile Hanesse (who Shrestha gives all the credit for breathing tasteful aesthetics into the house), Swotha has created quite a buzz in a span of just 10 months. Search for ‘traditional houses Nepal’ on google, and the second result is Swotha’s TripAdvisor review. It has 21 reviews with 19 ‘excellent’ ratings, and is ranked number one among 12 bed and breakfasts, and inns in Patan. With word of mouth complementing the accommodation, locals, visiting tourists, and even ‘potential’ tourists still planning the trip have heard of the traditional home. The entire venture is reflective of the nature of the investors who have taken an unconventional approach here. Their exposure and outlook is tangible in the way the Swotha project has turned out and in the way it is currently operating.

A CONSTRUCTIVE VARIETY

The stories of these restoration projects reflect a variety in approach, which resembles the assortment reflected in the history these residences represent – personal and unique. The interest to restore, however, is gradually becoming contagious it seems. Shrestha is helping some neighbors in his locality with restoration designs for their old residences. Ranjitkar says he knows many people interested in buying or leasing traditional homes for hospitality ventures.

But the sudden awareness of this potential has also created a real estate bubble. Shrestha shares how people in the vicinity have begun to suggest absurdly high prices even for storage use in an unused dilapidated house in the areas around. It may be a fragile bubble, and it may burst sooner or later. But, the awareness of the value of the location and the worth of the historic houses they live in, is a good sign. These may be just a few projects, but Nepalis putting in money and seeing this as a good business venture suggests a longer life for this architectural variety that is as important a facet of our history as the monuments we strive hard to preserve.