Born in a remote village in eastern Nepal, Novel Kishore Rai was destined to rise above the wildest dreams of his peers. He completed his PhD in linguistics, then went on to become a professor at Tribhuvan University in Kathmandu, and was appointed Ambassador to Germany in 1995.

A dusty lane wound away from the famous Dhobhighat pond near Jawalakhel and led its way to a double set of gates separated by a long passage. As I rang the bell at the second gate, loud barking greeted us, and judging from the sound, the beast seemed to be quite excited. A silver-haired man opened the gate, while the lady of the house subdued the dog. With palpable relief, I stepped inside and was ushered into the spacious green backyard. I settled down on a wicker, chair face to face with former ambassador, Professor Novel Kishore Rai.

For a professor of the Nepali language, and for one who has a PhD in linguistics, his name may be a bit misleading - more so for a person who has been researching two Rai - Kiranti languages, Chintay and Puma (spoken in and around Dhankuta and Khotang respectively). Professor Novel Kishore Rai, Ambassador to Germany from 1995 to 2000, explains simply, “A school master in my village in Panchthar gave me my name.”

Not many could have predicted that a boy from a remote village in eastern Nepal, born in 1947 to soldier/farmer Chandra Das Rai and his wife Deoshuri, would one day emerge as a top-notch academician and an ambassador for his country. The village had only a primary level school and Rai was the first student to pass class five from there. The professor’s eyes twinkle behind his spectacles as he recounts, “When mid-level education was introduced in the school, I was the only one to attend class seven!” Listening to him, I have to constantly remind myself that I am talking to an accomplished academician as well as a former ambassador. He has not lost his humility despite his accomplishments.

The professor’s words further reinforce the wondrous feeling. “I am the youngest among seven brothers and two sisters, and I am the only one who is educated.” He still remembers the name of his primary school, “It was called Shri Durga Prathamic Vidalaya.” Since there was no high school in his district, the young Novel went to Ilam for further schooling. But life was not by any standards smooth sailing for him, at least financially. He confesses, “I went for teacher training when I was supposed to be studying in class nine and actually, gave my SLC after studying only the one year in class ten.” An adolescent Novel was already drawn towards the noble profession of teaching. No doubt, the need to start earning early played a part in his endeavors. However, in 1968, Novel passed SLC in the 2nd division. After giving his Intermediate exams as a private student, he attended night classes in Saraswati College in Kathmandu. Living in Kamlakshi in Ason during his college days, he traveled to the outskirts of Thankot to teach in a school for two hours every day. “I passed out with a second division in BA,” he informs. Then, unable to contain himself, the professor laughs, “You could call me Mr. Second Class!” It is nice to see such self-deprecating humor in such an able man.

In 1972, Novel earned his MA in Nepali from Tribhuvan University as well as his MEd - both with second division. “I also earned a BL degree in 1976 as a private student. Second division again,” he chuckles. However, he was not that casual when it came to studying law. He admits that he has always been drawn towards the subject and would have loved to practice as well as teach law. “But things didn’t work out on that front,” he acknowledges. Armed with his degrees, he returned to his roots and joined the faculty in the college in Ilam as an assistant lecturer where he taught for six years. In 1986, he received his PhD in Linguistics from Poona University in India. “My doctoral thesis was titled ‘A Descriptive Study of Bantawa’, or in other words, ‘Bantawa Grammar’.” According to him, Bantawa is one of the many subdivisions of the Rai community. In 1987/1988, the academician earned the right to do his post doctorate at the University of Kiel in Germany as an Alexander-von-Humboldt fellow. Around the same time, he also became the first visiting professor from Nepal at the South Asian Institute in Heidelberg University.

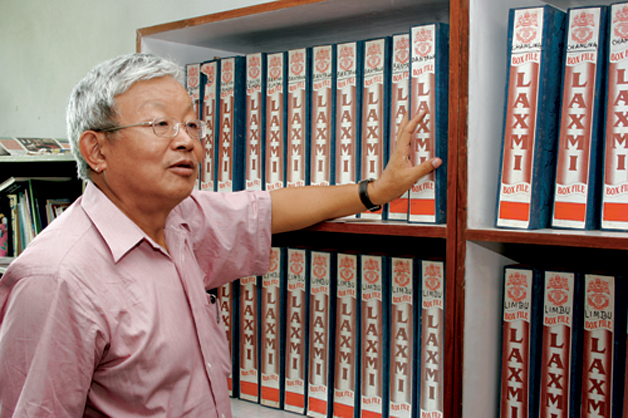

Rai at present is associated with the Centre for Nepal and Asian Studies (CNAS) at Tribhuvan University. He explains, “It is a collaborative effort with Leipzig University and we are making the first ever digitalized documentation on two Rai-Kiranti languages— Chintang and Puma.” He has been visiting Leipzig in Germany once a year as part of his work.

Reflecting on his life as an ambassador to Germany, he remarks, “At the time everybody thought that I was a member of the CPN (UML) because I was appointed Ambassador when they were in government,” he says. “But let me tell you, although I confess to having leftist leanings, I was never a member of any political party and don’t wish to be one in the future either. I would hate to be buried covered with a party flag. I wish to remain free of all such involvements.”

Still, being the country’s envoy for not only Germany, but also holding ambassadorial responsibilities for Switzerland, Poland, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and the Vatican City undoubtedly entailed much involvement with politics and politicians as well as a fair amount of duty. Recalling those high-flying days, the professor states, “Of course, those were interesting years even though I couldn’t travel to all the states much as I would have loved to. Purely financial reasons.” He sheds light on the position of an ambassador of a least developed nation: “Our embassy had a staff of only four people including me, and only two cars at our disposal. People on the outside may think that being an ambassador means a life of glory and grandeur, but that is far from the truth. Things were so expensive there that it was a struggle keeping pace with expenses.” As far as work was concerned he says, “There is a saying, ‘If you bow and speak, the man above you will not hear, and if you stand upright and speak, your words get carried away by the wind’. Such is the case most of the time, because among the many weighty matters of the world, and lost in a crowd of many important countries, a least developed nation like ours gets quite overshadowed.”

A realistic man, Professor Rai seems to have taken it all in his stride. He reveals, “You know, in diplomatic terms we used to describe our work as building relationships, but in reality all we were expected to do, was try and get more donations for the country.” The professor also clarifies, “During my tenure, I also taught Nepali at the Bonn University as well as at the Kiel University, for which I was roundly criticized by many people. Let me state that I did my teaching after 5 pm and with the consent of the government.” He also declares, “I did not accept payment for teaching. It was done as a matter of personal interest on a purely voluntary basis.”

Looking back, he says that the high point in his diplomatic career was when he got the Presidents of Germany and Switzerland to visit Nepal in 1996 and 1997 respectively. He explains, “The last visit by any president from these countries was way back in 1969. This was only the second such visit.” Apparently, the visits resulted in a substantial number of noteworthy joint projects in the country. The former ambassador also remembers, “Both of them stayed in Nepal for five days each, which is extraordinary, because visits of this nature are limited to two or three days at the most.” Nevertheless, Novel Kishore Rai laments, “During my tenure, the Nepali government changed five times! Due to this political instability, many of the things I had planned to achieve couldn’t bear fruit because no one could be held accountable for decisions taken then.” It was also during this musical chair period in Nepali politics that the infamous bill to allow parliamentarians and bureaucrats to import duty free cars was passed unanimously. Rai says, “I did not avail of the facility. I thought it was totally unethical for a government to allow such a thing.” As a matter of interest, Rai still doesn’t own a car.

Talking about the current situation regarding Nepal’s embassies, Rai opines, “It is about time Nepal established one in Latin America, as we don’t have any representation in that burgeoning part of the world. On the other hand, it is no use having one in Burma.” He further states, “And while our embassy in Egypt does mean that we have a presence in Africa, I believe South Africa would be a far better choice.” As for his peers, the professor has the highest regard for Kedar Bhakta Mathema, former Ambassador to Japan. “It is not just because he was my teacher as well as the Vice Chancellor of TU that I say this,” he asserts. “But Mathema is an active man - alert, intelligent, frank and physically fit – qualities that earned him respect from others, especially the Japanese.” Rai himself earned due respect for his efforts as an ambassador and was awarded the Gorkha Dakshin Bahu and the Trishakti Padak. From the German government, he received the Grand Cross of the Order of Merit.

On a more personal note, Rai is a born vegetarian and says, “Three generations of my family have been vegetarians.” This could be one of the reasons for his relatively good health, although he admits that he has a slight case of high blood pressure that he takes care of by going on regular morning walks. As one would expect, he has written books on linguistics that he hopes to publish after retirement. “If finances work out, I would like to have one book published every year.” When questioned about the possibility of further bureaucratic duties, he says, “Some time ago I was asked by the royal secretary, Mohan B Pandey, to put in an application. Similarly, the Vice Chancellor has also, on occasion, suggested that I apply for lucrative posts.” However, the professor seems to have no enthusiasm for such endeavors. He seems happy with the way things are at present, and perhaps feels there is no need for more glory. In fact, he is already planning an active retirement; something that he can well afford to do, what with wife Nirupa herself busy as a librarian and social worker at the Rato Bangla School, and daughters Numa and Ninamma doing their Masters. With fewer responsibilities in the home front, he looks forward to fulfilling his desire to do more of social service.

At any given time, Rai is on the board of a score of organizations in some capacity or the other. Thus, he is the President of the Toni Hagen Foundation, Vice President of Himal

Association, a member of SOS (Thimi), advisor to a dozen colleges, and a Rotarian to boot. Rai, a past president of the Linguistics Society, is its present Chief of publications, and is also a special guardian member of the Kirant-Rai Central Association. An advisor to the Janjati Maha Sangh, he was once its first general secretary. He discloses that he would like to be much more active in the social sector after his retirement two years down the line, but at the same time declares, “There are two things I don’t want to do - wear a safari suit and open an NGO.”

More than just your usual lapel pins

The lapel pin is a men’s accessory worn on the lapel of the jacket which serves as a...