What does the other }side of Nepal look like? The side so far-flung that it takes one or two days bus ride and a few days walk to reach; the side so withdrawn that our

progressive mind will take years to understand the jinx that has beset the people living there. You and I, of course, have heard a lot about the hardships people put up with everyday just to survive in those godforsaken corners. That is one way, though, of looking at it. The other way is to put our progressive spectacles aside and see it the way Jindagi, a pictorial book by a Swiss couple, shows us.

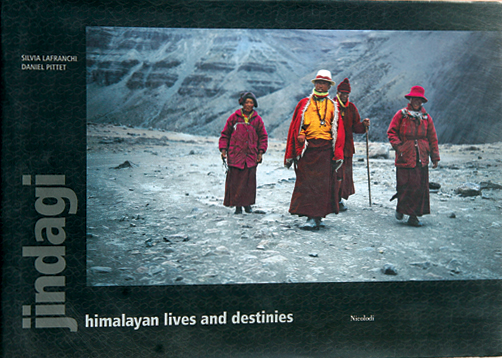

Silvia Lafranchi, writer, and Daniel Pittet, photographer, have lived and worked in Nepal for many years, most of them in remote areas, on the ground – the ground that poor farmers till season after season, that porters trudge across day after day; the ground that enriches with the dreams, hopes, sweat and blood of the rural Nepalese who live, struggle and perish there.

The story of one Baburam, a porter, is heart rending. He falls off a slope while carrying a heavy load and ends up bedridden. The feeling of being useless and a burden on his family drives him to cut his stomach with a razorblade. Writhing in pain, Baburam asks his oldest son to help him end his suffering.

On the other hand the tales of Dinesh and Sujan are full of hope and inspiration. Abject poverty does not deter a village boy like Dinesh who refers to bus as a metal house on four wheels and can barely say “hello” (the only English word he is familiar with)—to find a place for himself at the Institute of Forestry in Pokhara. Though he could not understand the questions (all in English) on exams, he got through, as “in practice he was also the only one who knew how to distinguish every single tree and shrub in the forest, and the only one who knew all the blossoming seasons and locations of each plant.” Dinesh finally goes to England and gets a Masters Degree with honors and returns back with a desire to “fight to allow even the poorest children to go to school and create the foundation for a less miserable existence.”

Silvia’s prose is so strong that even after being translated from Italian to English the book retains the essential Nepaliness in each story that she recounts. Though originally from Switzerland, Silvia’s strong grasp of Nepaliness echoes through almost every sentence in the book. The earnestness she has undertaken to understand life in the remotest corners of Nepal is evident in every chapter, as she recounts her experiences with different people and their family members.

Sujan, likewise, works as a dishwasher in a wayside tavern in the mountains. As the writer couple realize that the eight year old aspires to study they ask him to take them to his family to discuss the matter and help him enroll in some school. On the way they offer the boy a juice that he sips quite slowly. Thinking they might get late, the couple asks him to have the juice while walking to which he happily obliges. On reaching home the child “slipped a hand into the filthy pocket of his jacket and—without saying a word, with a knot in his throat from the emotion—he took out the container of juice almost full.” The couple were “moved by the scene” and were embarrassed to think “about the lightness with which we had gulped down our drinks while walking.”

The couple says that though the West has achieved a lot in terms of development, the warmth preserved by the tendered hearts like Sujan eludes those inhabiting developed societies.

Their rendition does not sound like a eulogy written for unsung heroes. It does, however, tells us that heroes are not only born in cities and towns, and that even the day to day actions of common Nepalese contain heroic acts.

Where many writers have portrayed the pain and sorrow of hapless rural Nepalese as a bottomless pit with no end in sight, Silvia and Daniel find joy and hope, and the desire to go on with what almost seems like a utopian struggle. As a narrator and photographer team, Silvia and Daniel do not come across as outsiders who harbor detached, sympathetic admiration for the simplistic life of rural Nepalese, but as people who have lived and shared some of the complexities of their hardships and the comforts of guileless moments of joy.

Published by Nicolodi in Europe. Available at Pilgrims for NRs 3200.