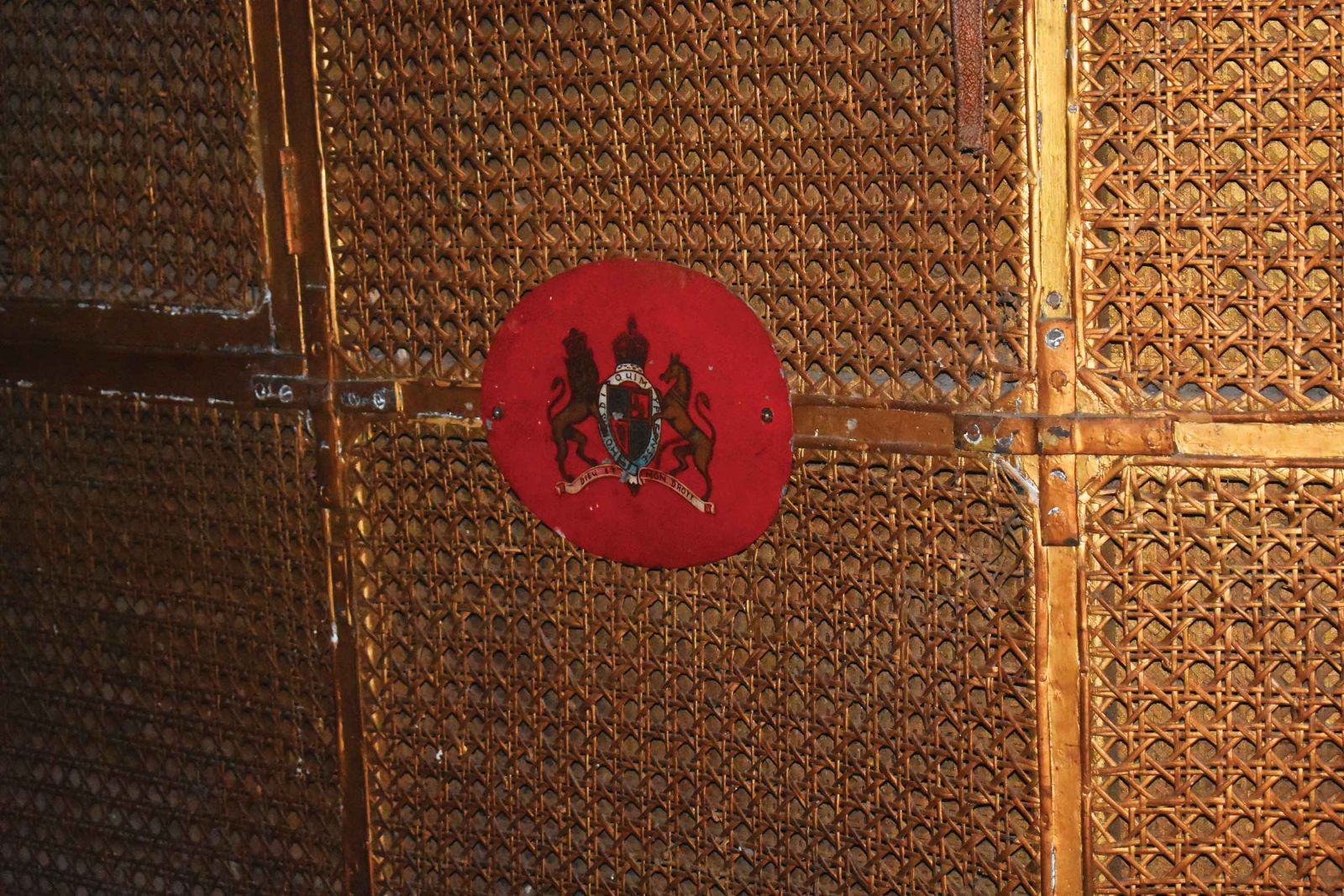

The building was sturdy-looking, impressive; the sort that looks as if it has stood for a hundred years and will stand for a hundred more. Stone, mortar, wood and history made up this Hattisar, or elephant stable. Stepping into the dim gloom of the interior, we entered what is perhaps the world’s only howda museum: this is the final resting place of the elephant saddles and chairs used by both local and foreign dignitaries over many, many years. Lit only by narrow, high windows, and looked after by an aging caretaker carrying on a family responsibility, this is not your average museum. Moving slowly through the space, peering at the unusual objects stored all around us, there was a strange sense of both history and timelessness. Here, the howda made for Queen Elizabeth and Prince Phillip’s visit in 1961, the royal crest still clearly emblazoned on its woven rattan side. There, a metal frame with a small seat in the middle, said to have been built by Jung Bahadur Rana himself.

“Traditionally, in the state of Nepal the elephant stable, the hattisar, was maintained primarily to facilitate royal hunting expeditions or rastriya shikar, which were lavish affairs that could last for months, utilise hundreds of elephants, and the labour of thousands (see Smythies 1942). Rastriya shikar perhaps reached its apogee during the… rule of the Ranas...”

(Piers Locke: ‘The Hattisar: The Integral Role of The Elephant Stable in the Apparatus of lowland Nepali Park Management’)

While those days are, of course, long past, this sliver of history is not. The howdas—we counted 44 of them and at least 20 saddles—mostly hang in neat rows around the room, in what could have once been elephant stalls. We are in Bhimphedi, after all, where people would pause on their journey between the lowlands and Kathmandu; a place where a royal party might mount their elephants for the journey south. And here, in the building, these unique and historical remnants of this long-ago time are unceremoniously gathered; dusty, fascinating.

Bhimphedi? Where’s that, you may ask, thinking as I did, that you’ve never heard of it. And while you may not have heard the name, it’s not true that you know nothing about it. It’s a place that was, for years, a literal witness to history, as kings, farmers, adventurers and everyone in between passed through it on their way to Kathmandu. The town was where the road from the south ended and the hike north began. So traders traveled through with their goods, as did kings and rulers heading down to the Terai, perhaps for a hunt or trip to India. Those cars you’ve seen being carried over the hills in those old photos—they all passed through Bhimphedi. In its time, it was one of the country’s most important hubs. But few now have heard of it. So I took a trip down there, for what turned out to be an unexpectedly enjoyable combination of travel and history, amplified by the fact that my companions on the trip -- Monica Sans Duran, Awasuka Program director in Bhimphedi, and Subodh Rana -- were extremely knowledgeable about both Bhimphedi and Nepal’s history overall.

We left the valley via Dakshinkali, our destination south and slightly west. A flat tire at Pharping led to the serendipitous discovery of the Auspicious Pinnacle Dharma Centre of Dzongsar, an unpretentious looking monastery that housed 16 huge, heavy prayer wheels; we made a circuit or three as we waited for the tire to be changed and headed once again on our way down the road.

The road, I should add, is bumpy. While I’ve certainly been on worse tracks and trails in Nepal, this one was all the more frustrating as it was easy to see that it had once been a great road, now fallen into disrepair. The narrow, winding space is filled with speeding Sumos, the favored local transportation and certainly more practical than buses would be on these roads; but even with our own four wheel drive vehicle, it was a jostling ride. The reward for our pains was beautiful, clear views; the proximity to Tihar meant fields covered in orange-yellow marigolds greeted us as we turned each new corner, and piles of fresh citrus awaited at each stop.

At the Deurali pass, we became enveloped in mist from one bend in the road to the next. Also, there had begun to be tantalizing glimpses of the ropeway, above and below us, which once carried goods between Hetauda and Kathmandu. The first had been built in the 20s, but the one currently visible was built by the Riblet Tramway Company between 1959-63. While no longer functional, the cables and metal enclosures that hang from them are still visible at points along the road, stretching off down to Hetauda in the distance. It’s amazing to think that these ropeways once carried supplies of all kinds from the south to the capital, and part of me wonders if reviving such a system (updated and modernized, of course) wouldn’t ease road congestion and vehicle pollution on travel into the valley.

Shortly after Deurali we passed Chisapani Gadi, a hilltop fort that apparently has great views of the surrounding area. It’s a historic location, and located on this erstwhile key travel and trade route and at an altitude of 1700 m, must have once been vital to the early defense of the valley. There’s a Batuk Bhairav temple there as well, but the whole fort area is off limits to women, and we did not stop.

From there it wasn’t much longer to Bhimphedi Bazaar itself, and as our vehicle began its descent there it was there, spread out below us, still looking remarkably like it looked in photos taken a hundred or so years ago.

Photograph by Arnau Montoya, Awasuka Program Team, Bhimphedi

The Hattisar, described above, was our first stop, as we wanted to see it while it was still light. It’s set inside a delightfully wild garden, full of unusual vegetables—I spotted a patch of black chilli peppers, something I was completely unfamiliar with—before continuing on our walk through the town.

We spent the night in Hetauda, about 45 minutes to the south, and returned to spend the next day exploring Bhimphedi and learning more about its history from those who live here. The Prithivi-Chandra Hospital, we learned, was once once second only in the country to Bir Hospital in Kathmandu. Another beautiful building once housed a bank, another the telecom office—these and so many others could be restored into truly special heritage destinations. It would take a lot of effort, no doubt, but they are a part of Nepal’s past that should not just be allowed to slip into obscurity.

We also visited the only building that remains of a palace said to be built for King Surendra Bikram Shah to use when he traveled, now located inside Bhimphedi’s Bal Mandir. Unfortunately we were unable to see another palace, built by Juddha Shumsher Jung Bahadur Rana and now located inside the grounds of the jail; it said to be one of the most striking buildings in the area.

Newars and their architecture are here too; the caretaker of the local Bhimsen Temple is originally from Sanga, and the temple’s statues and metalwork were brought here from Patan years ago, and several beautiful old buildings are adorned with the woodwork that is so prevalent in the valley. Much of it, though, is falling into disrepair; several buildings of historical import, such as the local school, have already been demolished, new structures going up in their place. One can only hope that a purpose can be found for some of these places, so that they will be restored and preserved.

Photographs by Arnau Montoya, Awasuka Program Team, Bhimphedi

Bhimphedi may not ever be a mainstream tourist destination, but if you are interested in history and architecture and the forces that shaped what the country is today—oh, and elephant saddles—I think you owe it to yourself to visit here at least once, before these pieces of history vanish for good. Everyone we met was friendly and welcoming, and it felt like we just slipped into the cadence of the place without any big ado. There’s a busy road that runs right through it, but so few people seem to actually stop. More should; it’s worth it. After so many years here, I wasn’t expecting the experience I had in Bhimphedi, but I’m always glad to learn how much more I have to discover about Nepal.

Getting there: You can catch a Sumo to Bhimphedi from Balkhu, from where they leave regularly. Another option is to rent a car or take your own—if you do, make sure it’s a four wheel drive. If you leave Kathmandu early, you could also make a day-trip of it, though it would be a long day: the trip takes about three hours each way.

Accommodations: There isn’t much in Bhimphedi in the way of places to stay, but a few people rent out rooms; one is Krishna Shova whom you can contact at 9745001010. A more comfortable alternative is to continue to Hetauda, particularly if your final destination is Chitwan or elsewhere down south. We stayed at Regal Hetauda Resort (057-523256), which was green, spacious and beautiful, but you’ll find multiple options across all price points to choose from in the city.