On January 15, 1850, Prime Minister Jang Bahadur Rana set off from Kathmandu on the first state visit by a Nepalese leader to England. His entourage of 42 included his two youngest brothers,24-year old Jagat Shamsher and 23-year old Dhir Shamsher, and a retinue of military and civil officials, and servants.Before leavingNepal they went hunting in the tarai, followed by brief visits to Dacca in Bengal and Patna in Bihar. At nearbyBankipur, Dhir Shamsher and Jang Bahadur performed a daring feat on horseback, ascending a 2½ foot wide spiral walkwayto the top of a gigantic brick gola(granary), 90 feet high.A day or two later they boarded a paddle steamer for the 11-day trip down the Ganges to Calcutta, the seat of British colonial government in those days.

On the river

Steamboat service on the Gangeshad begun only in the 1830s. Prior to that, and before rail and motor roads crisscrossed India, overland travel required a serious investment in time, horses, pack animals, servants, occasional short-haul ferry crossings, supplies and, for dignitaries and wealthy businessmen, a well-armed armed escort.

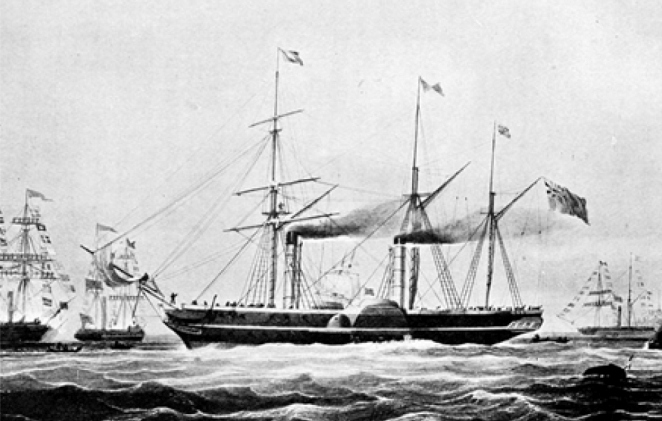

For the river trip, the colonial government accommodated Jang Bahadur’s entourageon the best available paddle steamer and offered allthe assistance they needed. For most if not all members of the party, the riverboat ride was their first experience traveling on a mechanically-powered, fire and smoke-belching conveyance. For passengers and freight, each Ganges steamertowed an accommodation boat. While riverboat service was mostly for the convenience of colonial officials and their families,other Europeans, and official Indian passengers, the luxury of it was also enjoyed by royalty and feudal princes like Jang Bahadur.

Theboats weremoored out each night, but when Hindus were on board the captain anchored up next to a high bank so that theycould cook and eat their meals ashore according to orthodox religious custom. Jang Bahadur was especially careful at mealtimes to avoid potentially polluting proximity to infidels (mlechha).

The comfortable novelty of ariverboat trip was not lost on its passengers, nor on villagers watching from shore.“Here come the boats,” writes an historian of the event –

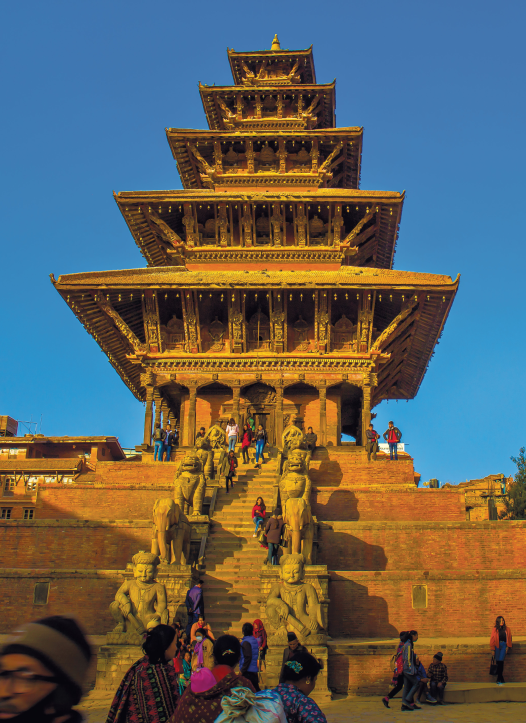

“An iron-hulled steamer in front churns the river to foam beneath its broad paddle-boxes, towing close behind an accommodation boat with green shutters along its sides and a striped awning fluttering above the top deck. Of all the sights offered to the humble, unsophisticated villagers along the Ganges’ banks, few could compare in interest. The billowing lug sails of country craft careening before a monsoon wind, carnivorous turtles and alligators sunning themselves on sandbanks, and lifeless corpses floating past were all too common to excite much attention. Grizzly river forts, mossy palaces, jasmine-scented pagodas, crumbling monuments, moonlit bathing ghats, and prayerful minarets of small village mosques, and Hindu gods and goddesses marvelously carved in stone, were too familiar to rank as wonders matching boats that were moved by smoke and fire.”

Arriving at Calcutta

The route took them to the river delta through the Sanderbunds and on to Calcutta’s ferry boat landing at Chanpal Ghat on the Hoogly River, a major distributary. A regiment of British troops and a military bandgreeted them at the wharf and a welcoming salute was fired from the ramparts of Fort William. During their stay in Calcutta, Jang Bahadur and party met colonial officials and attended several receptions. He and Dhir Shamsher, the most military-minded of the brothers, were especially interested in visiting the fort, arsenal, gun-cap factory and other military installations, a small sampling of what they would see on a much grander scale in England. The final event on the eve of their departure for England was a grand Durbar hosted by the Viceroy, Lord Dalhousie.

Next day, on April 7, the Nepalese party boarded the S.S. Haddingtonto beginthe first leg of their sea journey to England. As the ship departed, it is said that Jang Bahadur’s escort from Nepal, numbering eight hundred men of the Rifle Regiment, who were there to see him off “burst into tears―poor, ignorant men, to whose imagination a sea voyage was so full of horrors as to be equivalent to death!”

―――――――――――――――

The quotations are from ‘Steamboats on the Ganges’ (1960)by Henry Bernstein, and ‘Life of Maharaja Sir Jung Bahadur’(1909) by Jang Bahadur’s son Padma Jang Rana, who wrote of the European trip largely from his father’s diary.