Gaijatra was started to show a queen that she wasn’t the only one to lose a loved one. Today it continues to help people who have lost their own realize that they are not alone in their grief as well.

All my life, I have watched Gaijatra processions from the windows of my mamaghar (uncle’s home) in Bhaktapur. Waking up to the commotion inside and outside the house, and then enjoying the whole day listening to ghintang ghisi, bhajans and pyaakhas (traditional dance) has a different feel to it. With relatives crowding the house and neighbors and strangers crowding the porch, Gaijatra always meant noise, fun and enjoyment. Last year was a different story.

When Baa (grandfather) passed away on January of 2012, I thought that for a family of seven (at my uncle’s), we would find it impossible to move on with our lives. For all of us, he had been the source of inspiration, strength, belief and love. But as I made my way through Bhaktapur’s alleys and crossroads for last year’s procession, I knew that a lot has changed in just eight months. We had become stronger and more confident.

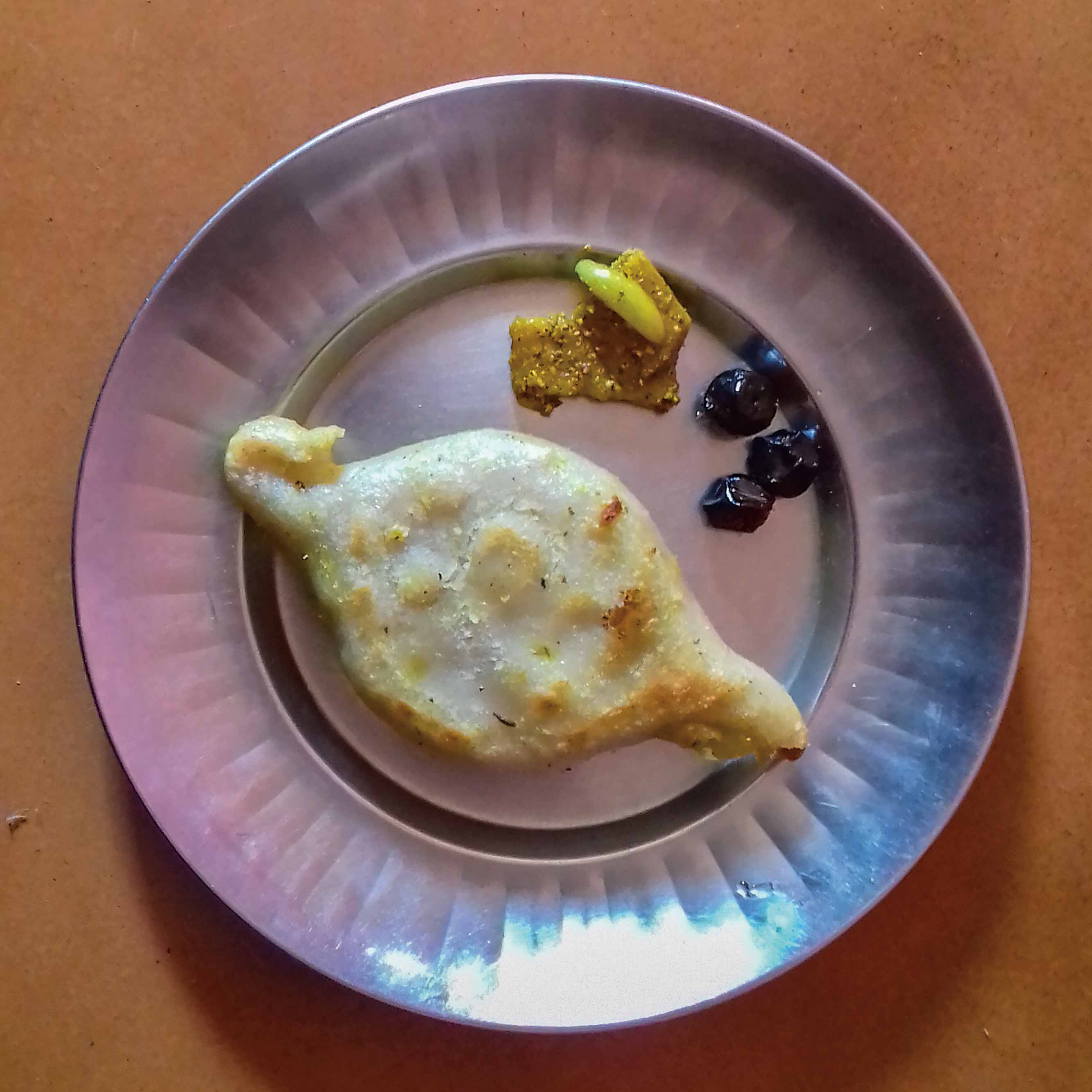

A few days prior to the festival, we started shopping for requirements and other preparations. Unlike others, mama had opted for packets of juice and biscuits to give away, taking out the hassle of making three hundred and sixty swari and malpuwa. Cloth for shirts, patuka and white cloth were bought to wrap around the taahasha (a chariot like long structure made from bamboo). Similarly, a dhime baja group of local youth was fixed and Baa’s portrait was commissioned to be made by a local artist.

When the festivities finally started, both of my uncles, mother and maizu (uncle’s wife) forgot their anxieties and started to prepare for the procession. The taahasha was first made by neighbours outside the house while relatives poured in to help with kitchen and puja work. A pair of horns made out of straw and a picture of a cow’s face were kept on the top of the taahasha. After the taahasha was prepared, our family priest helped my mother start the puja and soon the procession started from our home in Tekhapukhu towards the rest of Bhaktapur. While walking as a part of the procession, right after the bhajans and other times before the famous ghingtang ghishi, I had time to wonder about what Gaijatra and all the rituals after death could actually mean.

At some point, I realized that these traditions exist to help the grieving family to move on with life by distracting them in a way. Although family members are traditionally ‘in mourning’ for an entire year, most of the time is used in preparing for the different rituals. The family is kept busy buying and making things, and planning for the next ritual once one is done.

These traditions help them move on with their lives while at the same time allowing them to accept the fact that their loved one is no more. You become so busy that you don’t realize a whole year has passed till the annual sharaddha. All these rituals also help the grieving members regain composure. This is how I came to conclude that although Gaijatra was started to show Pratap Malla’s queen that she wasn’t alone in her loss and as a traditional way to record deaths, it has survived the passage of time because it helps us move on and realize that none of us are never really alone. n