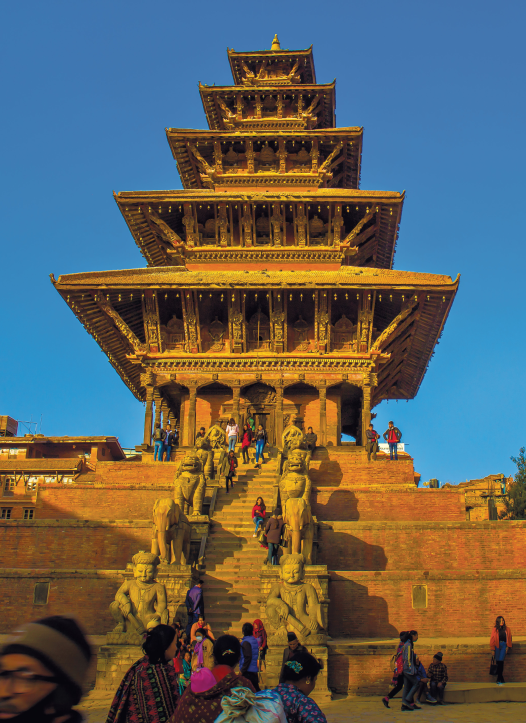

Late one summer day a green kite soars, weaves and sways in the seamless blue sky while its proud owner, a scraggy little boy in his early teens, oblivious to the scorching midday sun, his ruddy face covered in sweat and grime, twirls a wooden spool. Suddenly a yellow-red bapachya appears from nowhere, spoiling for a fight. The boy steals a glance at the invader and steadies himself, bristling with excitement.

The bapachya (a bi-colored kite) veers towards his own kite, straightens, soars up skywards, whirls and then comes tearing down. The green kite ducks, smartly dodging the oncoming rush, propels itself up above the challenger and then deftly homes in with an unrelenting dive, taking the bapachya off guard. As both lock, a battle begins with baited breath. The kites spin away as lines are fed. All at once the babachya falters, then plummets down in a wild descent. “Chait!”, bellows the

The bapachya (a bi-colored kite) veers towards his own kite, straightens, soars up skywards, whirls and then comes tearing down. The green kite ducks, smartly dodging the oncoming rush, propels itself up above the challenger and then deftly homes in with an unrelenting dive, taking the bapachya off guard. As both lock, a battle begins with baited breath. The kites spin away as lines are fed. All at once the babachya falters, then plummets down in a wild descent. “Chait!”, bellows the

victorious owner of the green kite at the top of his lungs in a true battle drawn cry.

Although age has caught up with me, now in my mid-50s, I think back to those days every Dasain when the sky is speckled by vibrant red, blue, yellow, green, you name it, in a wonderful kaleidoscope. Old memories rush back in virtual reality, of that spool-toting little chap lost in a world of his own with his kite. How on earth can I fail to remember those wonderful priceless moments drenched in excitement and drama, let alone that small wide-eyed, heady, little fellow? Simply because, I am he.

In the 1960s, a time of no ‘tellys’ and of long tiring waits for movies to change at the handful of theatres (in those days a movie ran for several weeks), for the youngsters of Kathmandu the only way out to unleash themselves during the long awaited Dasain holidays was to fly kites, run kites and, more than that, to fight kites. For me it was an obsession. I whined, scrounged, stole, threw one too many tantrums at home, and did not mind trading mom’s frequent thrashing for a day’s kiting. I still remember how the corrugated-sheet roofing of my house leaked when the monsoons came as it had to bear the brunt of my wild stomping each Dasain. There was never a dull moment flying and fighting kites. When the holiday escapades were over, what remained of the tell-tale cuts, gashes, and rashes, all so heroically ignored through the entire Dasain, stood out as endearing reminders of a beloved season that had once again passed a little too soon.

In those days the kites, the bapachyas, ankhes, fatuwas, dariwals and what-not, cost from half a rupee to two rupees apiece, depending on their size. The bigger and the fancier ones with watermarks like long stripes that ran across the crisp paper cost six to eight rupees, though always considered a luxury by us. The strings available then were the plain and lightly waxed, unlike the ready-to-use glass coated ones that you find aplenty today hanging by their spools in the kite shops. A motley array of wooden spools hung in the shops, too, in all sizes to suit your pocketbook. The kites came from Calcutta (Kolkata) and Patna, the strings from Bareily (India), while the wooden spools were made by the local carpenters. For us, Ason, with only a handful of kite shops, was the hub for all the kiting paraphernalia.

Now before we could have a go at flying, one crucial piece of work remained—the maza ritual. Maza is a concoction comprising of linseed oil (aalas), arrowroot powder, sago grains (sabdana), a slippery extract squeezed out of a cactus plant called ghyukumari and powdered glass, was brewed to a thick consistency and then applied to the string. All this stuff was sold at the same kite shops save for the powdered glass which we prepared ourselves by pounding light bulbs and sifting it through a muslin cloth. The cactus was foraged from the neighborhood. Every boy prided in his maza recipe, which he kept secret as success at kite fighting rested upon it.

With the sun high, the maza application begins as two spools, one loaded and the other blank, are readied, held by two boys while the chap with that pot of thick messy concoction scoops up a fistful, holds the line in between and as the line is fed to the blank spool, the index finger and the thumb of the other hand presses the passing line to enable a uniform coat. Ritual accomplished, the spool with the coated line is then laid out in the sun to dry. Given a bright sunny day, the strings take a little over three hours to dry and

become battle ready.

Now I do not profess to have been an ace fighter in those days but I did hold some clout over my neighborhood peers. When in my elements, I downed 7 or 8 kites against a loss of only 2 or 3, considered an admirable feat among my friends; but there were days, too, when only frustrating defeats came by. I had friends who were great at kite running; but I had no stomach for it as it called for speed and brawn that I lacked, and as often as not it ended in scuffles.

Then one Dasain our entire neighborhood was in for a big shock—an invasion out of the blue. A newcomer had made a storming entry, blazing a cutting spree across our sky. He spelled doom to every single kite that dare cross his path. None stood a chance and none were spared. It really stung when I lost kite after kite to this formidable adversary.

What really intrigued my friends and I was his style of launching an attack. To all flyers of our genre the rule of thumb was to secure an upper hold over the opponent’s, ensure full contact and feed the line in a steady slow motion. This way the odds against a win stood 1 to ten. To the bewilderment of all the flyers of our neighborhood, this chap did just the other way round by engaging himself from below. Another of his tactics that left us gaping was when he kept hauling in his line instead of feeding it.

His kite approached from below, tore straight up and before we were prepared to meet this unexpected rush, our lines snapped upon contact, as it were they had been touched off by a razor blade. For two days the cutting binge continued, and all we did was gawk at our hapless kites. None of our ruses seemed to work against this seemingly invincible warrior. Overnight this newcomer had turned a hero, talked about in hushed tones whenever the boys met in the alleys. Words got out; this fellow from a Nepalese origin was up from India visiting his uncle who lived in our neighborhood.

Near desperation, I decided to pay a visit to this mystery fellow, a dark horse—just a stone’s throw away from my house. I found him, a guy almost my age, flying his kite, to my great surprise, with his bare hands. No boy in Kathmandu then, I daresay, flew with bare hands. An assistant stood by his side holding a spool and fed the line when needed. Even as I watched awestruck at the ease, the flourish, and the control he displayed, tugging and jerking on his line, he downed two kites to their doom in barely ten minutes.

Anxious to get to the bottom of this enigma, I cautiously struck a conversation with him, “Wow! That was great—two kites cut in less than ten minutes. You know what; this is the first time anyone has struck off kites in this inimical style of yours.” The fellow smiles at me and said, “Well, it’s nothing. In India we fight kites this way.” I had to pry into, so I pushed on “It really beats me how you do it ’cause we only spar by paying off our line.”

“It’s very simple,” he volunteered “If you are mounting your attack by drawing your line, you got to maneuver from below when you go for the kill. Care must be taken that the upward surge is maintained at a very fast and unbroken pace. If you manage a rapid tug, your line kept taut, it has a devastating effect on your opponent’s line”

“So what’s the other guy supposed to do to foil this attack?” I egged him on. “Again very simple,” pat came his reply, “All he has to do is make a dive for it to meet the onrush as fast as he can till the lines get into full contact. Then if you are a feeder type, let go your line. This way the other guy won’t stand a chance.” For me it was a revelation—in truth, a fait accompli.

The next day, as expected, I had a showdown with him. I followed the newcomer’s instruction to the letter and launched an attack. Lo and behold, I could not believe my eyes when down went his kite. The day followed with three more victories against one loss for me. So, after all, this guy was not as invincible as all the local boys and I had come to believe. One should have watched me then, swaggering down the street my chin held high. Be that as it may, he had by all counts caused quite a stir in our neighborhood like never before. For two more days the dog-fights between us continued, each vying to outwit the other, scores almost neck and neck. Our kites dominated the sky, as if the rest did not exist. Only four days, and a strange camaraderie had developed in between us, though our kites were at perpetual war.

On day five he was gone—just like that. Later I learned he had left for India. For many Dasains that came thereafter, as the pirouetting kites flashed in vibrant hues and shades against the indigo sky, I truly missed him. I even tried flying with bare hands after him. I pulled it off with fantastic results, but soon gave up, as I always ended up with countless bleeding cuts and gashes from the maza. Those nostalgic moments I shared with him had left behind only haunting memories encapsulated into the deep recesses of my mind even to this day.

Ravi Singh is a sportsman and writer who lives in Kathmandu. He may be contacted at ravimansingh@hotmail.com.