Time is of the essence. Time is money. Where time stands still. Timeless love. Time waits for no one. Time is the fourth dimension.The place that time forgot. Our concepts of time are captured in the truisms of our culture. Now, as we bideshis are living in another culture(outside our culture of origin), we are also living in a sense in another time, and in another sense of time.

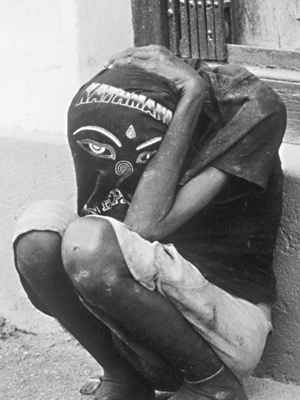

I recently took part in a photo exhibition entitled Mapping Modernity in Nepal. The premise was that Nepals traditions and ways of life are being influenced and shifted by modern ideas, devices, technology, and patterns of living, from Valentines Day and Hindi movies to motorcycles, mobile phones and kerosene torches to water pollution and skylines distorted by electric wires to AIDS billboards to prosthetic legs, even to the prevalence of wristwatches. While Kathmandu seemed to be the epicenter of the changes, they were also recorded in villages that sported satellite dishes, huge piles of beer bottles, and so on.

I recently took part in a photo exhibition entitled Mapping Modernity in Nepal. The premise was that Nepals traditions and ways of life are being influenced and shifted by modern ideas, devices, technology, and patterns of living, from Valentines Day and Hindi movies to motorcycles, mobile phones and kerosene torches to water pollution and skylines distorted by electric wires to AIDS billboards to prosthetic legs, even to the prevalence of wristwatches. While Kathmandu seemed to be the epicenter of the changes, they were also recorded in villages that sported satellite dishes, huge piles of beer bottles, and so on.

When I spoke about the exhibit, I noted that even though it is 2003 (or the Nepali year 2059) all over the world, there seemed to be some equation of modernity with phenomena that originate outside of Nepal, in more industrialized countries, as though those places exist at a later point in time. This compliments the sense that many foreigners have when we visit remote villages in Nepal: that we are going back in time. Clearly some elements of those villages have remained more constant over the years than parallel elements in the city: people still marry at young ages, still use the stream for their drinking water, still weave mats from local grasses to sit on, etc. There are mixed reactions to this constancy: on the one hand a delight in and nostalgia for the natural rhythms of life that are found in the village, and on the other a sense that the people have been deprived of basic advances in science and technology (often though not always correctly equated with longevity and quality of life) and opportunities to explore the larger world. (When we refer to a village or society as backwards are we also referring to an earlier place in time? Is there an assumption in the negative connotations of the term that everything improves with time?) In Kathmandu, the sense of stepping into an earlier era is not as prevalent, yet in certain places and moments- such as Pashupatinath or Durbar square at Teej or Indra Jatra- one can feel a wind from ancient times still

stirring across the stones.

Maybe part of the reason we think of technological changes as belonging to a later period in time is that more technological societies move at a faster pace. Cars move at dangerously fast speeds on the German autobahn and U.S. highways, everyone from doctors to college professors to workers on assembly lines is expected to constantly increase efficiency, packaged foods and microwave ovens dramatically shorten individual food preparation time, and so on. If we move faster, have we actually traveled further in time? And is this connected to the discontent with the present that is common in many of our cultures? Are we not only eager to leave behind this computer for the new model, this old fashion for the new, but also this moment for the next?

I am sometimes amazed at the patience most Nepalis seem to have for sitting around and not knowing when something is going to happen; in general Nepalis sense of time seems to be less urgent and more situational than mine. The right bus will come by, eventually- probably- two hours ass-okay, well catch a ride in a truck. It’s raining; well do it tomorrow. The thulo manches (important people) are too busy now; make the request next week. Send out the invitations today for the event tomorrow. This adjusting to the present elements rather than enforcing a schedule may reflect the difference between a primarily agrarian society and a primarily industrial one. I appreciate the reminders to consider interaction with people and the environment as important as my own and others goals for production.

Where I come from, in the U.S., one is expected to have a plan, that is to put time to use. Here, by contrast, I recently asked a friend why he likes Hindi movies so much, and he said it’s a time pass- as though he had a surplus of time! On my trips back to the U.S., I am sometimes startled at what I can accomplish in one day: the errands, the purchases, the communications take place at breakneck speed. But at the end of the day I sometimes can’t remember all that I did, or more than a few of the people I interacted with. Was it just another form of time pass? Or was the balance of all of this flurry of activity- which may have included many miles driven in a car that produced air pollution as well as e-mailing an insightful column about motherhood to meet a deadline, and much more-creating some greater benefit?

Bringing the expectations of time from our own countries, we westerners are often frustrated at how long it sometimes takes to get things done here. The electricity goes out, the manager has disappeared for an extended tea break, there is an event in the royal family and all the roads are blocked off...and the project that seemed so urgent is just not going to get finished today. In those situations, we are presented with an opportunity to be in the moment, to face that life is not under our control, and to appreciate what is actually in front of us: the hues of the sky, the smile on a face, the taste of tea... a chance to come to know a place and some people by un-busily being present. And we may find our frustrations are compensated by those times of synchronicity that seem to occur here more often than elsewhere- like when you were thinking about a particular subject and out of the blue a friend handed you exactly the book you needed, and later that day you met the author.

Awarely or not, we foreigners in Nepal are time travelers, bridging different senses of time and histories of development. What can we learn, how do we want to shift our approaches to time; what do we have to teach and what warnings do we have to offer from our cultures approach to time?

Some lesser-known vegetable dishes from the southern plains

I’m not a vegetarian but I love vegetables. And whenever I get to the southern plains of Nepal, I try...