Hemp. The first thing that might flash through your mind upon hearing this word is ganja, the image of a cannabis leaf, illegality, Bob Marley, or even vague memories from your teenage years. But as many people involved in Nepal’s natural fibers industry are hoping, this word will soon invoke the image of a viable and thriving textile industry which can play a significant role in boosting Nepal’s economy. In a nation with few exportable natural resources, but many unemployed people, especially in villages where no practical source of income exists, hemp and other natural fibers can be, or rather are becoming, the next big thing.

The use of hemp for textiles, however, is nothing new. People have been cultivating hemp longer than any other textile fiber. Its textile use goes back as far as 8000 B.C. when it was first woven into fabric, eventually providing 80% of the world’s textiles. By 2700 B.C. hemp textiles, as well as other medicinal uses for the plant, were incorporated into a majority of the cultures in the Middle East, Asia Minor, India, China, Japan, and Africa. Within the next 1000 years, hemp grew to be the world’s largest agricultural crop and provided for many important industries such as fiber for textiles and ropes, lamp oil for lighting, paper, medicine, and food for humans and domesticated animals. All this comes as no surprise considering that hemp is the largest and strongest plant fiber, twice as strong as the ubiquitous cotton. Because it is extremely abrasion and rot resistant, it was the primary source for canvas, sail, rope, as well as clothing, military uniforms, shoes, and baggage until man-made fabrics were introduced. It fell out of popularity in the west as manmade materials slowly gained popularity. Though not as practical environmentally and not as sustainable, they became the primary textiles as economical and political considerations were made by governments who wanted to promote industry.

The use of hemp for textiles, however, is nothing new. People have been cultivating hemp longer than any other textile fiber. Its textile use goes back as far as 8000 B.C. when it was first woven into fabric, eventually providing 80% of the world’s textiles. By 2700 B.C. hemp textiles, as well as other medicinal uses for the plant, were incorporated into a majority of the cultures in the Middle East, Asia Minor, India, China, Japan, and Africa. Within the next 1000 years, hemp grew to be the world’s largest agricultural crop and provided for many important industries such as fiber for textiles and ropes, lamp oil for lighting, paper, medicine, and food for humans and domesticated animals. All this comes as no surprise considering that hemp is the largest and strongest plant fiber, twice as strong as the ubiquitous cotton. Because it is extremely abrasion and rot resistant, it was the primary source for canvas, sail, rope, as well as clothing, military uniforms, shoes, and baggage until man-made fabrics were introduced. It fell out of popularity in the west as manmade materials slowly gained popularity. Though not as practical environmentally and not as sustainable, they became the primary textiles as economical and political considerations were made by governments who wanted to promote industry.

Generally, the hemp plant, scientifically known as Cannabis Sativa, is best known for three things: narcotics from its leaves, oil from its seeds, and white bast fiber from its stem. It is a self-sustaining weed that can grow in many climates, but a mild humid climate (such as that of Nepal’s hill regions) is the most suitable for fiber production. And because this plant has been around in Nepal for centuries, Nepali people have used it for all its purposes historically. For centuries, villagers have extracted fibers from both hemp and wild nettle plants to weave mats, sacks, bags, fishing nets, ropes, and carry straps. Communities that are days away from roads, have learned to rely on themselves to provide textiles, rather than relying on deliveries from outside. However, in modern Nepal, hemp does not find much use as cheaper, machine-made, materials are widely and easily available.

The process for fiber extraction, the way it is done by hand in Nepal, is slow and involved. The plant is mainly harvested in August and then left out to dry. It is then soaked in water for several days. Afterward the plant’s fibrous portion is teased out, twisted, sun dried, beaten (to soften it), and spun. But that’s not the end of the process. After spinning, the thread is boiled with water and wood ash and, finally, washed many times. However, as laborious and time consuming as this process may be, the result is a crudely processed and rough material that, by today’s standards, cannot be used for clothes.

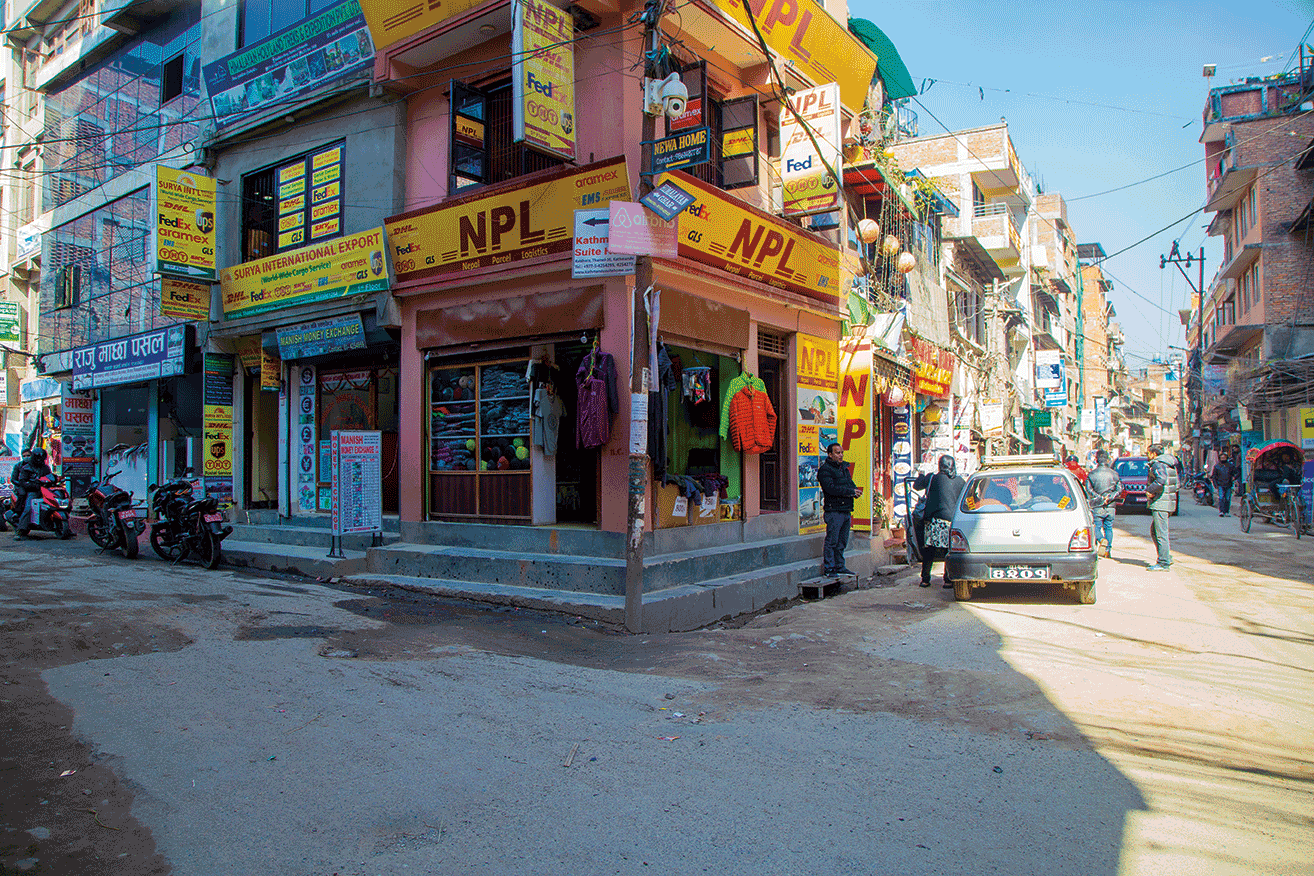

Although today you will find scores of hemp goods dealers and exporters around Kathmandu Valley, very few are using locally grown and processed hemp for their natural fiber clothes. The fact that hemp harvested and processed locally, is too rough for wearing against the skin, entrepreneurs must import finely processed hemp fiber and material from China. Basu K.C. of Basu Export House, whose shop is located in Thamel and has a factory in Kalanki, deals with many hemp garments, but imports all his hemp fibers and materials from Nepal’s northern neighbor, though he would like to use fiber from Nepal. Dealers like Sana Hastakala, of Kupondole in Patan, do use local hemp, which generally comes from areas such as Rolpa and Rukum. But they are able to produce only accessories like slippers and bags from the coarse material. Besides, in the current political situation, it is very difficult to access and collect hemp from these heavily affected Maoist areas. Because of obstacles like this, they (and other companies) rely more on allo, Nepal’s wild nettle.

The natural fibers industry in Nepal is not only a matter of business, but also a matter of rural and economical development. Both hemp and nettle do not use up arable land, valuable in Nepal’s mountainous terrain where endless plains where food can be grown do not exist. If it is grown properly, hemp can even be extremely beneficial for soil structure because of its deep root system and production of biomass. Basu K.C. describes in his company profile that, “As a bark fiber, rather than a seed fiber like cotton, hemp grows well without herbicides, pesticides, fungicides, or chemical fertilizers.” Furthermore, both hemp and nettle are easily renewable. Focusing on hemp’s social benefits, Sharada Rijal writes in her company’s profile, Milan Garments, that her objectives are to “provide employment opportunities to the underprivileged section of society” and “to utilize locally available resources and manpower in the production and operations process.” If hemp could be grown and processed on a larger scale right here in Nepal, it would provide desperately needed jobs and a source of income for villagers who have no options for work in their villages.

K.C. described his vision for the hemp industry in Nepal. If the hemp entrepreneurs of the Kathmandu Valley could unite to form an association, then with their pooled resources they could create a training center in a remote area of Nepal to teach the villagers how to cultivate the hemp up to the fiber stage usefully, by hand. Currently, their methods produce a rough result which can be used only for accessories such as bags, wallets, and hats. How ever, once taught, they could produce a fiber that can be used for finer hemp textiles for clothes. What Nepal also lacks is a processing unit for yarn, a properly equipped factory in short. This is another reason entrepreneurs have been forced to import from China. Yet with their pooled resources, they could build such a processing center, allowing them to keep Nepal's hemp production and raw material actually here in Nepal. According to K.C. he alone spends about US$2000 to US$3000 on imports from China.

At this point in time, technically, hemp is illegal. Still, no one is farming hemp in Nepal; they are merely making use of those plants that are growing naturally. But hemp entrepreneurs realize the potential of this plant and want the industry to thrive openly and freely. The Handicraft Association of Nepal (HAN) now has a Natural Fiber Sub-Committee to help in the promotion and progression of hemp and other natural fibers. Sharada Rijal of Milan Garments, also the committee's coordinator, explained that their main focus at the moment is the legalization of hemp. The committee also supports other natural fibers like allo, but they are already legal and it is hemp that really needs attention. Rijal explained that the demand for Nepali hemp products in Europe, America, Australia, and Japan is so high that "every year we cannot fulfill the demand." According to official statistics from HAN, Nepal's hemp suppliers exported NRs. 27 million worth of hemp goods in the fiscal year of 2001/2002. Because of this, and to support Nepal's economy, the country's hemp entrepreneurs united more than half a year ago to apply for a permit from the government to grow industrial grade hemp, which is what the Chinese, as well as many other nations such as Russia and France, are growing. It also belongs to the Cannabis Sativa plant genus (as do both broccoli and cauliflower), but contains only an insignificant level of intoxicating substance. Industrial grade hemp is not marijuana. It is taller (about 3 to 5 meters tall) and stronger than the average hemp plant that grows wildly-- perfect for harvesting fibers.

HAN, particularly the Natural Fibers Sub-Committee, is also working to promote hemp in other ways with a five project plan. First of all, they want to train villagers on the weaving and processing process in order to improve the final outcome of hemp textiles. Their idea for training also includes entrepreneurs here in the city as well. HAN has already conducted a buyer and seller meeting to exchange ideas among those in the industry. A national seminal and international exhibition of hemp products are currently in the planning stages, too. The sub-committee is also publishing information about the current situation of hemp in the nation. They want the government and local people to understand that hemp is a fabric, not a drug.

Hemp is eco- friendly; it's sustainable; it's versatile and it can provide jobs. The list goes on. Many entrepreneurs in Kathmandu are trying to advance it, and not just to help themselves. They see the potential of this "weed." As Sharada Rijal put it, "We want to promote our people, our farmers." And she thinks the future looks bright. If only the government would allow legal cultivation of industrial hemp, the industry could really prosper. And so could Nepal. Hemp has the potential to revolutionize the textile industry and rural development. So while many in the west are fighting to "Legalize It!" just so they can "smoke and fly," Nepalis are fighting to legalize it so they can support their country and its villagers. As a result, hemp products are not only a fashion, but also a statement. So, optimistically, soon people will be free to openly cultivate fiber from the best plants available. When it comes down to it, what really is the problem with it? It's only hemp. It's only natural.