Trekking to Mustang District’s high mountain shrine of Muktinath is a challenge, one that has attracted pilgrims for over two millennia since its time in prehistory as a simple ‘nature shrine.’ Then, as now, the ‘miracles’ of Muktinath attract huge crowds of pilgrims each year. Trekkers, too.

Pilgrims on the trail along the Kali Gandaki river near Kagbeni

Before 1976, when the Jomsom airport was opened, Muktinath was only reachable on foot. And now, for the past year or so, visitors have been able to bus to within a few minutes’ walk of the shrine on a rough new motor road. Pilgrims like the road. Trekkers walk.

To accommodate off-road trekking, the Annapurna Conservation Area Project (ACAP) has recently opened ‘Alternate Routes’... Zealous pilgrims have walked to Muktinath for well over two millennia from all across South Asia. But foreign trekkers hoofing it to the shrine is relatively new, dating only to the 1950s, and mostly since the 1980s. The trekkers come for many reasons: because of Muktinath’s location in the heart of the Himalayas, for the mountains, for the shrine’s fame as an ancient Hindu pilgrimage destination and, not least, to walk through what may well be the world’s deepest/steepest gorge on their way north. The geology is outstanding. The gorge horrendous. The views impressive. The people generous. And, Muktinath is a sacred and scenic gem.

Among the first foreigners to visit Muktinath was H.W. (Bill) Tilman, the inveterate British mountaineer/explorer who saw the shrine in 1950. Some of Maurice Herzog’s French Annapurna expedition members also visited Muktinath briefly that year. And, in 1956 it was toured by David Snellgrove, a British Tibetologist who documented its religious (particularly Buddhist) significance. In October 1964, before I first set off for Muktinath with a Peace Corps friend, we read about it in Tilman’s Nepal Himalaya (1952), Herzog’s Annapurna (1953), and Snellgrove’s Himalayan Pilgrimage (1961). They are all good reads. Another good source on Muktinath is Corneille Jest’s Monuments of Northern Nepal (UNESCO, 1981).

To get there, we walked the centuries old trail that pilgrims have trod for centuries. It took us well over a week from our starting point, old Pokhara bazaar, in Nepal’s mid-hills. I’ve done it several times since then, and it’s always a challenge.

Since March 1976 there’s been air service to Jomsom from Pokhara. Beyond Jomsom (at 8,900 ft) it’s still a long walk to mountain shrine (over 3,500 feet higher). Doing it in two days’ is best, recommended, with an overnight stop in Kagbeni at the confluence of the Muktinath (or Jhong) and Kali Gandaki rivers.

These days, all that walking is optional. Busses, jeeps and motorcycles now regularly drive all the way, including the dangerous passage through the gorge where the road is cut across a perpendicular cliff face above the roaring river a few miles south of Ghasa.

Dhumba Lake

What is the enduring attraction of Muktinath? There are many great trek destinations in Nepal, but Muktinath is one of the best and oldest, first “trekked” by pilgrims well before it was first written about in the third century BC. Muktinath has long been known for several “miracles” - wondrous to behold. It undoubtedly started out as a simple “nature shrine,” and over the centuries has become a storied destination of great religious significance.

The ‘Miracles’ of Muktinath: Water, Fossils and Fire

The natural wonders of Muktinath include its cold springs, ancient fossils, and natural methane fires.

Cold water springs. The cold water springs gushing copiously from the mountainside above the shrine are believed by many to flow underground directly from sacred Lake Manosarovar near Mount Kailash in western Tibet. At the shrine, the water has been channeled through 108 cow’s head spigots, directly behind the Vishnu Mandir, a temple dedicated to the god Vishnu, Hinduism’s ‘Lord of Salvation.’ The cow is sacred to Hindus, the number 108 has special significance to Tibetan Buddhists, and the Vishnu Mandir is the centerpiece of the temple complex.

All pilgrims are expected to bathe in the frigid waters, to cleanse body and soul from sin and to attain spiritual ‘liberation’ or ‘salvation,’ the mukti that gives the shrine its name. At auspicious times each year, the shrine is crowded with Hindus from the lowlands who have come to worship and immerse themselves both literally and figuratively in the waters and the spirit of the place.

Saligram fossils. The shrine also owes its sanctity to the presence of sacred saligrams, the local name for the black ammonite fossils found in abundance in the upper Kali Gandaki region. Hindus worship the saligram as a representation of Lord Vishnu. To Tibetan Buddhists it represents Gawo Jogpa, a serpent deity. Ancient Hindu texts assure the faithful that wherever a saligram is present, so too is Lord Vishnu.

Geologically speaking, these ammonites date back 165 million years to a time when this high-rise landscape lay covered by mud at the bottom of the shallow Tethys Sea, well before the Himalayas pushed up to their supreme heights. You can well imagine the look of wonder in the eyes of pilgrims from the lowlands when they find encrustations of ancient sea creatures so high in the mountains.

Pilgrims on the trail from Kagbeni to Muktinath

Natural gas fires. To most pilgrims, the most astounding sign of the gods is the presence of two natural but small methane gas vents burning from earth and water. They are enshrined in a temple called Jwala Mai (or Jwalamukhi), a few minutes’ walk south of the Vishnu Mandir. Inside Jwala Mai, for the donation of a few rupees, the faithful can view the tiny blue flames burning dimly under a dark altar. Overhead, atop the altar, several Buddhist deities stare out somberly, unmoved.

The “miracle of Jwala Mai” was first described in English by the Tibetologist David Snellgrove. In the book about his 1956 visit Snellgrove wrote that “The flames of natural gas burn in little caves at floor level in the far right-hand corner. One does indeed burn from earth; one burns just beside a little spring (‘from water’); and one ‘from stone’ exhausted itself two years ago [1954] and so burns no longer, at which local people express concern.”

The flames are a focal point of immense curiosity and veneration. Pilgrims stand in awe of them as a powerful sign from the gods. And, because fire and water are incompatible in Nature, they are considered to be super-natural.

Fire is an important element in Hindu Vedic ritual. It represents Agni, God of Fire, and it is considered a gift from Lord Brahma himself. Buddhists, for their part, interpret the flames as “burning changeless and unceasing from the hidden [sexual] parts of Samvara Male and Female [a tantric deity and his consort],” says Snellgrove. Both religions interpret fire as a fundamental element of Creation itself.

Religious Syncretism

In Tibetan, Muktinath is Chumig Gyatsa, meaning a place of “a hundred-odd springs.” The main deity, Hinduism’s Vishnu, is Buddhism’s Lokeswar (Avalokiteshvara), the protective deity of Tibet, incarnate in the Dalai Lama. Hindus and Buddhists alike worship at Muktinath, and while a Hindu pujari (priest) is sometimes present at the Vishnu Mandir, the entire complex is maintained year round by Buddhist nuns of the Nyingmapa sect. That such a high mountain shrine is revered equally by followers of both religions is an example to the world of a remarkable tolerance and religious syncretism.

All of these fabulous miracles are what attracts pilgrims of each faith to Muktinath. Zealous pilgrims focus unwaveringly on the ritual aspects of the journey, step by step. The richness of their experience also adds to the attractiveness of Muktinath for modern day foreign trekkers, though only a few may appreciate the full significance of the site. The mountain scenery and other geological wonders undoubtedly impress trekkers the most, especially the awesome Kali Gandaki gorge.

Pilgrims bathing under the cow’s head spigots at Muktinath

The Kali Gandaki Gorge

The Kali Gandaki river cuts dramatically through the Himalayas at a point several days walk south of Muktinath, between Ghasa and Dana, deep down between Dhaulagiri (the world’s 7th highest peak) and Annapurna-I (the 10th highest). The gorge is extravagant geological and hydrological entertainment. The chasm through which the river churns and roars, and disappears briefly, is extraordinary. Not only is it amazingly deep and steep (combined), but it may also be, deep down at its base, one of the narrowest canyons in the world.

South of the gorge, the scenery is typical mid-hills Nepal. North of it, well before reaching the Muktinath valley, the trekker passes on through Thak Khola, an open valley that stretches from Ghasa and Lete/Kalopani past Larjung, Tukche and Marpha to Jomsom, the district town. The river flows as a relatively flat meander through Thak Khola. This stretch of valley is known for its strong daytime winds. Over it all stands the great white sentinel, Dhaulagiri. Thak Khola is home to the Thakali ethnic group, a trading people. For centuries the old trade route to and from Tibet, and the pilgrim track to and from Muktinath, passed through their villages on the west side of the valley. The new road is there now, on west side of Thak Khola where most of the inns and guesthouses are located.

The gorge lies south of Thak Khola, between Ghasa at the north and the junction of the Rupsé Khola and the Kali Gandaki at the south. The Kali is at its deepest and narrowest here, some dozens of meters upstream from where the Rupsé Khola (river) joins it. On a map, Rupsé is north of Dana and immediately below Kabré village. You’ll know you are there when you see the Rupsé Chhahara, a spectacular waterfall that tumbles off the high cliffs. There are several tea shops in view of the waterfall, making it a popular stop for trekkers.

Do the math. Let’s look at the gorge with a mathematical eye, starting at the top of the gorge. If you draw a line in the sky (on a map) between the tops Dhaulagiri and Annapurna-I (D1 to A1 in the box), it crosses directly over the village of Kokhéthanti, a small village located on the east bank of the Kali slightly over a mile upriver from Leté/Kalopani. The depth of the valley at Kokhéthanti is 3.2 miles (‘d’ to ‘b’ in the box), and the slope to the top of Dhaulagiri is approximately 48.8% (1:2.1). That’s steep!

Trekkers on an alternate trail down the east bank of the Kali Gandaki

Now if you draw a second line from Dhaulagiri to Annapurna South (D1 to AS in the box) it’ll cross over Ghasa, approximately 3.5 miles deep (‘c’ to ‘a’ in the box). And, because the river at Ghasa is actually a few hundred meters lower than the village, it’s deeper yet. The Ghasa-Dhaulagiri slope also impressive, about 34.6% (1:2.9).

There is one more impressive point in the gorge. From the peak of Dhaulagiri (26,795 ft) draw another imaginary line southeasterly out to a point over the gorge directly upriver from the Rupsé Chhahara tea shops. The bottom of the gorge here is at an altitude of 5,575 m, fully 21,220 feet – 4 miles! – below the top of Dhaulagiri. The slope here is approximately 30.2% (1:1.3). Looking northeasterly towards the Annapurnas, the slope is slightly more, approximately 36.3% (1:2.6).

None of these figures are to scoff at. They demonstrate why this gorge is considered among the very deepest/steepest in the world. An engineer friend put it into perspective: “A 45° angle is a 100% slope,” he said. “That may not seem steep, but if you are at the top looking down, it’s a scary descent.” (See the box for more statistics.)

As amazing as this is to adventurous foreign trekkers with their backpacks, hiking poles, and digital cameras, to pilgrims who walked it in the past, and who now cross it by jeep or bus, the cliffs along the gorge present a fearful passage. Over the millennia a good many barefoot pilgrims must have slipped and fallen to their deaths from the original narrow footpath etched across the face of the cliff north of Kabré. If you look closely from the trail on the east side of the gorge, parts of that original track can still be seen as a precariously thin line high above the freshly blasted road.

Accidents still happen. In October 2011, an overloaded jeep full of pilgrims fell hundreds of feet down the cliff, killing 14 people. It occurred in the worst possible, most dangerous spot called Bandargunj (‘Monkey Place’). A British trekker who rode a bus along there a week later summed up the experience in two words: “Never again!” The view from the bus, he told me, was straight down the rock face hundreds of feet into the roiling depths.

Porters on a bridge crossing the Kali Gandaki near the river gorge

The New Road

The new motor road now goes all the way through the gorge across that cliff, and up through Thak Khola beyond Jomsom to Kagbeni. From there, it turns east up the Muktinath river valley to stop a few minutes’ walk from the temple complex. Travel on the road goes in stages, with several changes of vehicle. It is not recommended.

Among Thakalis, the road has generated both satisfaction and controversy. To some it’s a boon, providing a fast and inexpensive way to get local produce out to market – especially apples, for which the district is justifiably famous. Others consider it a bane, particularly roadside (formerly trailside) hotel keepers watching bus after bus full of potential guests roar past in clouds of dust. Only a few strategically located towns like Jomsom and Kagbeni are benefitting much from the road.

Today’s pilgrims are taking full advantage of the new motorway. They can now ride speedily (if scarily) up from the south all the way to Kagbeni and Muktinath, where they perform their ritual ablutions. Then, in a few days (not weeks as before) they’ll be back home pursuing their otherwise busy lives.

I got a glimpse of the impact of the road when I visited Muktinath on the eve of Aunsi (the new moon festival) at the start of the 2010 Dashain religious holidays. Somewhere between two and three thousand pilgrims crowded the riverbank at Kagbeni before sun-up that day, observing shraddha, a Hindu memorial for the dead. Then, from Kagbeni many of them hiked on up to Muktinath, a steady five to six hour climb along the trail above the south (left) bank of the Muktinath river. Others rode in jeeps up to the shrine along the rather more circuitous and bumpy route over the hills high over the north bank of the river.

My companions and I hiked the Kagbeni-to-Muktinath trail chatting with some of the lowland Hindus who were pleased to be walking up this last short section of the long trail their forefathers walked generations before. That walk, however, takes its toll. Pilgrims periodically drop out along the way to rest. (Me, too.) It is a difficult ascent, steep in parts, up from 9,200 feet at Kagbeni to 12,475 feet at the shrine, an ascent of 3,275 feet (nearly 1,000 meters). That’s a strenuous endeavor for lowlanders, the vast majority of whom have never before been this far into the mountains, nor at such altitudes. Their feet were sore, they said, and their lungs ached. The strain of it showed on their faces, but then so did their zealous determination. Most wore shoes or sandals on the rocky path. Only a rare few followed the precepts of the ancient texts, which admonish them to go barefoot all the way.

When we arrived at the shrine in the early afternoon we were confronted by huge crowds in line to worship at the Vishnu Mandir. And behind it, men in shorts or loin cloths and women in thin cotton saris dashed under the 108 spigots spewing frigidly cold water. After that they dipped, full immersion, into two sacred pools at the front, all the while praying to the gods and shivering. Everywhere it was “standing room only.”

Trekkers take note. The crowds at Muktinath are sporadic, occurring only a few times a year during especially auspicious Hindu festivals, such as Janai Purnima (in August), Aunsi before Dashain (in late September or October), Chhaite Dashain (in the spring), and others. I’ve been to Muktinath at times when it was deserted except for the nuns who maintain the site.

<

View beyond Titi towards Chhayo village on the alternate east bank trail above Ghasar

The Wisdom of Ancient Texts

Hindu pilgrims flock to Muktinath for many reasons, not least because according to the Puranas (ancient Hindu texts) worshipping and bathing there liberates the soul from sin and evil. In this, Kagbeni and Muktinath are almost co-equal. While every place where two or more rivers converge (called a beni) is considered sacred, bathing at Kagbeni is especially efficacious, so high in the Abode of the Gods – the Himalayas, so close to the deities. As Lord Skanda assures the faithful, “Dear sage, the confluence of the Muktinath and Gandaki (Kagbeni) is very sanctifying.”

It is easy to understand the attraction. The Skanda Purana says that a bath in these holy waters automatically liberates the worshiper from sin, even the most vile of scoundrels including thieves, murderers and drunkards. And the Varaha Purana goes on to inform us that such devotion not only frees one’s self from sin but liberates one’s forefathers as well. Furthermore, says Lord Varaha, “I will be merciful to such a person. After death such a person will definitely attain Brahma loka” (literally the ‘cosmic spirit world’ or heaven).

For the unfortunate who died in the jeep crash in the gorge, the Puranas also say that those who die on the banks of the Gandaki “will definitely be liberated and will be free from the fear of birth, death, old age and disease” (from endless reincarnation, that is).

For trekkers, the mountain scenery is a main attraction, though the historical and spiritual aura of Muktinath and the pilgrimage adventure may also be important to a few. Some trekkers make Muktinath their ultimate destination, though many come and go without knowing much about the shrine. Muktinath is on the downward end of the two-to three-week ‘Round Annapurna’ Circuit route, which begins in Lamjung and Manang Districts (at the east) before crossing the 17,700 ft Thorung Pass west into Mustang District. By the time most Annapurna Circuit trekkers cross the pass and descend 5,226 feet down steep switchbacks to Muktinath, they are usually so exhausted that they walk right through the temple complex without appreciating its historic and religious importance.

Alternate Routes to Muktinath

Alternate Routes to Muktinath

The new road is having a significant impact on trekking, though most trekkers have a negative opinion of it, sometimes to the point of utter disgust. They see it as spoiling the great scenery of the valley and mountains with all the noise and dust and confusion that it generates. One experienced travel agent I know, has called it “a nightmare – dusty or muddy depending on the season, and always rough, bumpy and uncomfortable.” Between Beni and Rupsé, for example, there is no alternative to walking the road, and after passing that way near the end of the last rainy season he said, “It was horrible, insane.”

As early as April 2008, an article in Kathmandu’s Rising Nepal newspaper described the negative impact of the road on tourist arrivals. “The number of trekkers visiting the Annapurna Circuit,” it said, “has gone down sharply due to the construction of roads along this popular trekking route,” as much as 44% below the previous year, it said.

That’s the bad news. But, don’t let it deter you.

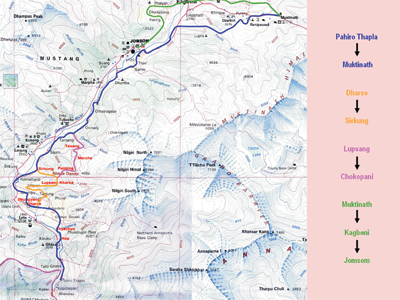

The good news is that the Annapurna Conservation Area Project (ACAP) has opened up new trails that avoid the roads as much as possible. ACAP has mapped, marked and inaugurated what it calls ‘Alternate Routes’ all across the region, trails that few pilgrims will ever take and where no jeeps or motorcycles will ever run. (The accompanying map shows only the Alternate Routes to Muktinath. There are more all across the conservation area.)

The ACA is largest of Nepal’s protected areas, covering five mountain districts. And, besides the Kali Gandaki gorge, two of the world’s highest mountain peaks; it also features one of the world’s highest lakes. The straight line distance between the lowest point in the gorge and Tilichho Tal (lake) at 16,136 feet is barely over 15 miles with an altitude gain of 10,561 feet. But because Tilichho peak (23,405 ft) stands directly between them, there is no easy route. The point is that the Annapurna Conservation Area offers some astounding geographical relief over some very short distances.

My companions and I trekked some of the new trails to and from Muktinath in October 2010, and we can attest to their attraction and peacefulness. True, we returned to the roadside hotels each night, but that was a minor glitch in our largely off-road adventure. Only when we had no choice other than walking some sections of the road did my companions grumble (especially from Tatopani hot springs down river to Galeshwor near Beni bazaar).

When we left Muktinath to return to Jomsom we had two off-road choices. We could have taken a high steep route over the hills south of the shrine to the Tibetan-like village of Lupra, the site of an ancient Bonpo monastery. Instead, we took the more popular alternate trail that comes out at the Kali Gandaki river a few miles south of Kagbeni at Eklai Bhatti (‘Lonely Inn’). After lunch in a roadside hotel we trekked south into the blustery wind down to Jomsom, walking the river flats, off road, as much as possible. Along the way we found several small black ammonite fossils underfoot.

South from Jomsom the alternate trail crosses to the east bank, climbs up past the Thakali village of Thini, on past colorful buckwheat fields and a crumbling ruins to sacred Dhumba Lake, then down to Chairo, a Tibetan refugee village. The old Chairo Gomba (monastery) is interesting to see. It is located in a juniper forest and is currently being restored by a group of international architects and artisans.

We had already walked the Dhumba lake portion of this trail a week earlier on our acclimatization hike after flying into Jomsom. So instead, on leaving Jomsom we walked the west bank trail/road down to the charming village of Marpha. For the most part, we took a footpath along the river to avoid the motor vehicles higher up. We arrived early, and spent the rest of the day exploring Marpha. The next morning we crossed the Kali to hike the alternate trail down the east side of the valley. That route is very pleasant, and while physically challenging in a few places, with some steep ascents and descents, it passes through quiet forests that periodically open up to spectacular views of the valley below and the snow peaks above. We had lunch at a riverside inn run by a young Magar ethnic woman.

That afternoon, we crossed to Kalopani and checked into a comfortable hotel. The next morning we walked the west side road part way, sometimes detouring on a rough forest path, down to Ghasa. The alternative would have been the east bank trail up and over a forested ridge and down through the Titi valley, past Titi Lake, to Ghasa. In retrospect, we should have taken the Titi trail, but our time was running out. The moral is: don’t be in a rush.

Below Ghasa, we crossed back to the east bank, and walked a well worn trail all the way down to Rupsé Chhahara. The valley drops almost 1,500 feet here, and the stone steps on parts of the descent were a bit rough on our legs; but far better than walking the road that is cut into the cliff on the other side. From several vantage points, we peered directly down into the depths of the roaring river gorge, and up the dangerous cliff that hangs over it.

All along the Muktinath trail, both on and off the Alternate Routes, the trekker sees many temples, monasteries and chortens (religious monuments) of the Buddhist and Bonpo (pre-Buddhist) religions, as well as Hindu sacred sites. This is a unique social landscape with mostly Thakali ethnic villages, cultures and festivals, with their strong ties to traditional Tibetan lifestyles. The hotels and inns along the way serve up some of Nepal’s finest ethnic cuisine, Thakali khana of rice, lentils, spicy vegetables, meat curries and hot relishes. Traditional Thakali food is far better than most of the pseudo-European items on the menus, though I’ll have to admit that Thakali hot apple pie is good anytime. There are also the scattered ruins of several medieval forts along the trail, and numerous apple orchards (for which Mustang District is justifiably famous). The fruit brandy distilleries at Tukche and Marpha are good for a tour and a taste, but be forewarned: the local booze is powerful stuff.

As your travel agency staff and anyone who has walked it will tell you, the Muktinath trail along the Annapurna Circuit has long been one of Nepal’s best and classic treks. The experiences you’ll have (and that we had) here are undisputedly outstanding: the riverine scenery, lakes and waterfalls, local cultures and religious sites, colorful flora and fauna (the bird-watching is brilliant!), and, not least – mountains, mountains, mountains.

Despite the road, the Muktinath Trail is still on, and in many ways because of the road it is all the more interesting. It continues to be a challenge, but one well worth trekking.

The author is a contributing editor to ECS Nepal magazine. He may be contacted at don.editor@gmail.com. He is also author of ‘Muktinath: Himalayan Pilgrimage, A Cultural & Historical Guide’ (1992) currently out of print but forthcoming soon in a new and extensively revised edition. He thanks his companions Ana Quinn, David Wolf and Pat Lambert for their congeniality on October 2010 trek, and John Lamb for his assistance with some of the statistics. He also thanks ACAP staff for providing maps and reports on the ‘Alternative Routes’ initiative. Our 2010 trek to Muktinath was masterfully arranged by Mustang Trails Trekking & Expeditions of Kathmandu at mustangtrailsnepal.com.

ELECTED PUBLICATIONS FEATURING MUKTINATH

by historians, orientalists, anthropologists & early travellers

-

1952. H.W. Tilman. Nepal Himalaya. Cambridge University Press.

-

1961. D. Snellgrove. Himalayan Pilgrimage. Bruno Cassirer (1st ed.) & Shambala (2nd ed., 1989).

-

1979. D. Snellgrove. ‘Places of pilgrimage in Thag (Thakkhola)’. Kailash: A Journal of Himalayan Studies (Nepal) v.7, pp.73-170.

-

1981. C. Jest. Monuments of Northern Nepal. UNESCO.

-

1992. D. Messerschmidt. ‘Social process on the Hindu pilgrimage to Muktinath’. Kailash: A Journal of Himalayan Studies (Nepal) v.9 (no.2-3), pp.139-157.

-

1992. D. Messerschmidt. Muktinath: Himalayan Pilgrimage, A Cultural and Historical Guide . Sahayogi Press. (Out of print; new edition forthcoming.)

-

1993. F.K. Ehrhard. ‘Tibetan sources on Muktinath’, Ancient Nepal (Nepal) v.134.

-

1994. R. Kaschewsky. ‘Muktinath: A pilgrimage place in the Himalayas’. Geographia Religionum (Germany).

-

2000. D. Snellgrove. Asian Commitment. Orchid Press.

-

2001. Jampal Rabgyé Rinpoche. The Clear Mirror. Muktinath Foundation International (see: www.muktinath.com/buddhism/mirror1.htm).

-

2002. R.K. Dhungel. The Kingdom of Lo (Mustang). J.S.P. Bista for the Tashi Gephel Foundation.

-

2003 (1953). G. Tucci. Journey to Mustang. Ratna Pustak Bhandar (2nd English ed.; original in Italian).

-

2008 (2065 V.s.). M.S. Ramanujadas. Muktikshetra Mahathmyam (2nd ed.). Sriman R.S. Ramanujadas (Nepal). (Translations of relevant Puranas.)

-

Ancient Sources

-

Mahabharata (Vol.2) and several of the Hindu Puranas (‘Ancient Texts’).

-

On South Asian pilgrimage in general

-

1963. A. Bharati. ‘Pilgrimage in the Indian tradition’. History of Religions v.3, pp.135-167.

-

1973. S.M. Bhardwaj. Hindu Places of Pilgrimage in India. University of California Press (1st ed.) & 2003, Munshiram Manoharlal (India, 2nd ed.).

-

1927. N.L. Dey. Geographical Dictionary of Ancient and Medieval India. Oriental Books Reprint (India).

Websites

A recent Internet search netted over 1,000 ‘hits’ on ‘Muktinath’. In addition to trekking company ads (the majority), the following are informative and useful:

www.muktinath.com or www.muktinath.org. This award-winning site (they are both the same) features Buddhist and Hindu background information, photographs, maps and reference books, advice on going there, and the Muktinath Foundation.

For a Hindu religious perspective, see www.veda.harekrsna.cz/encyclopedia/muktinath.htm and www.bhuj.swaminarayansatsang.org/Darshan/nepal.htm. For an introduction to some of the Buddhist attributes see: www.yetizone.com/muktinath.htm.

KALI GANDAKI RIVER GORGE STATISTICS

PEAK ELEVATIONS

D1 Dhaulagiri-1 8167m (26,795ft)

A1 Annapurna-1 8091m (26,545ft)

AS Annapurna South 7219m (23,684ft)

NPs Nilgiri Peaks (3) 6990m (22,935ft avg. elev. of 3 peaks)

TkP Tukche Peak 6920m (22,703ft)

TIP Tilicho Peak 7134m (23,406ft)

RIVERSIDE ELEVATIONS

‘b’ Kokhethanti 2545m (8350ft)

‘a’ Ghasa 2027m (6650ft avg. elev. of town)

‘e’ nr Rupse Khola 1707m (5,575ft lowest point)

DISTANCE, MID-POINTS & AVERAGE HEIGHT BETWEEN PEAKS

D1–A1= 24km (15mi), avg. elev. at ‘d’ 8,129m (26,670ft)

D1-AS = 26km (16.2mi), avg. peak elev. at ‘c’ 7,693m (25,240ft)

‘d’=midpoint on imaginary line between D1-A1

‘c’=midpoint on imaginary line between D1-AS

D1-‘d’= 8km (5mi) A1-‘d’=16km (10mi)

D1-‘c’=12.5km (7.8mi) AS-‘c’=13.5km (8.4mi)

DEPTH OF VALLEY

At Kokhethanti (‘d’-‘b’) = 5134m (16,844ft) = 5.1km (3.2mi)

At Ghasa (‘c’-‘a’) = 5666m (18,589ft) = 5.7km (3.5mi)

Nr Rupse Khola (D1-‘e’) = 6467m (21,217ft) = 6.5km (4 mi)

SLOPE (the higher the percentage, the steeper the slope)

Kokhethanti (‘b’) – D1 48.8% (1:2.1, – A1 25.2% (1:4), –AS 18.6% (1:5.4)

Ghasa (‘a’) – D1 34.6% (1:2.9), – A1 35.7% (1:2.8), – AS 27.8% (1:3.6)

Nr Rupse Khola (‘e’) – D1 30.2% (1:1.3),- A1 36.3% (1:2.6), – AS 31.8% (1:3.1)

ALTITUDE CHANGE

From Tukche at 2591m (8500ft) to Dana at 1402m (4600ft) is a distance of c. 20km (12.5mi) & an elev. drop of 1189m (3900ft) or c. 60m/km (197ft/mile)

(m=meter, ft=feet, km=kilometer, mi=mile, nr=near, elev.=elevation, avg.=average, c.=approximate)