The early years of Dorjee Karmarong’s life read like something out of one of the Himalayan folktales that the artist has illustrated in book form over the course of his career. Dorjee’s parents were rural migrant workers returning by foot over the mountains from Ladakh to their village in western Nepal when his mother gave birth to him in a cave. The Boudha-based artist reads from beautifully handwritten notes in Tibetan script which he has prepared before our meeting. Though the birth took place without incident, when the baby was born it was encased in a mysterious layer of skin which Dorjee, now 32 years old, likens to a football. Dorjee’s mother, taking a big risk, cut open the ball with a knife only to discover a healthy baby boy within. Soon afterwards his parents asked a lama in another nearby cave the meaning of what had happened. The lama told them that as long as the boy embraced the dharma, his unusual birth would serve as an auspicious portent.

It was not difficult for the young Dorjee to embrace his dharma. His home village of Khari is situated in Karmarong, an area of sparsely populated steep highland valleys in Upper Mugu which is largely unknown to the outside world even today. It is a place that was and still is deeply imbued with the traditions of Tibetan Buddhism. Perhaps the only literature available on the area is a book written and illustrated by Dorjee himself called The Turquoise Mountain which sets down in writing for the first time an ancient Karmarong folktale.

It was not difficult for the young Dorjee to embrace his dharma. His home village of Khari is situated in Karmarong, an area of sparsely populated steep highland valleys in Upper Mugu which is largely unknown to the outside world even today. It is a place that was and still is deeply imbued with the traditions of Tibetan Buddhism. Perhaps the only literature available on the area is a book written and illustrated by Dorjee himself called The Turquoise Mountain which sets down in writing for the first time an ancient Karmarong folktale.

Although Dorjee never attended school, he retreated to a gupha (Nepali: cave) for five months at the age of seven to learn the rudiments of reading and writing in Tibetan from his father who was a village lama. The following year, having acquitted himself well in the first gupha, he shifted, along with four other boys, to another gupha where he remained for the next three years under the tutelage of his grandfather, another village lama. This custom, known as chhaam in ethnic Tibetan communities, was strictly enforced in Dorjee’s case. For the entire three years the four young trainee lamas were not permitted to visit their families or enter their village. It seems to have been here, in this second gupha, where the foundations of rigorous discipline which have characterized Dorjee’s artistic career to date, were first laid down.

At the age of thirteen, after several years of migrant work in Nepal and Tibet, Dorjee was sent to a monastery in Kathmandu on the recommendation of his grandfather. Dorjee recalls that though his father accepted the recommendation without too much concern, perhaps remembering the oracular pronouncement of that first lama, the plan caused much grief to his mother at the time. She felt deeply anxious on account of the unhealthily humid climate with which highland villagers have traditionally always associated the Kathmandu valley. That concern coupled with thoughts of the fearful chaos of Kathmandu’s traffic laden streets made Dorjee’s parting with his mother a painful one. This is in fact a theme which Dorjee is currently revisiting by illustrating a modern Karmarong folktale written by a childhood friend.

At the age of thirteen, after several years of migrant work in Nepal and Tibet, Dorjee was sent to a monastery in Kathmandu on the recommendation of his grandfather. Dorjee recalls that though his father accepted the recommendation without too much concern, perhaps remembering the oracular pronouncement of that first lama, the plan caused much grief to his mother at the time. She felt deeply anxious on account of the unhealthily humid climate with which highland villagers have traditionally always associated the Kathmandu valley. That concern coupled with thoughts of the fearful chaos of Kathmandu’s traffic laden streets made Dorjee’s parting with his mother a painful one. This is in fact a theme which Dorjee is currently revisiting by illustrating a modern Karmarong folktale written by a childhood friend.

Dorjee entered Samye monastery in Maharajgunj and remained there for seven years. Describing himself as a ngakpa - a monk whose primary focus of study is on ritualistic performance rather than textual analysis - Dorjee explains that he was granted enough freedom in his daily monastic duties to begin to realize his creative abilities. Story telling seems to come quite naturally to this artist.

He recalls a time when his European sponsors, a married couple from France, sent him an illustrated children’s book depicting a talking parrot which would be let out of its cage by its owner in order to answer the phone. Somehow the story resonated with the young monk and he spent many hours drawing his own version of it which he then sent in the post to his sponsors – his first ever work of art. Although he remembers spending hours watching painters adorn the walls of Khari gompa as a small boy, some creative spark seems to have been kindled properly for the first time by those teenage sketches of the talking bird. Soon afterwards Dorjee became apprenticed to a thangka painting guru, a master of the traditional Tibetan art form from Sikkim called Palden. Under Palden’s guidance, Dorjee began to immerse himself in the esoteric world of thangka iconography with its countless geometric rules and proscriptions regarding, amongst other things, the proportions, shapes, colours, stance and attributes of the deities being depicted.

He recalls a time when his European sponsors, a married couple from France, sent him an illustrated children’s book depicting a talking parrot which would be let out of its cage by its owner in order to answer the phone. Somehow the story resonated with the young monk and he spent many hours drawing his own version of it which he then sent in the post to his sponsors – his first ever work of art. Although he remembers spending hours watching painters adorn the walls of Khari gompa as a small boy, some creative spark seems to have been kindled properly for the first time by those teenage sketches of the talking bird. Soon afterwards Dorjee became apprenticed to a thangka painting guru, a master of the traditional Tibetan art form from Sikkim called Palden. Under Palden’s guidance, Dorjee began to immerse himself in the esoteric world of thangka iconography with its countless geometric rules and proscriptions regarding, amongst other things, the proportions, shapes, colours, stance and attributes of the deities being depicted.

Well versed in religious lore from an early age, Dorjee was in a better position than most lay artists to appreciate the subtleties of this most traditional of art forms. He explains that the production of any single thangka incorporates a three-tiered process. First the image must be conceived of in the mind of the artist’s patron, traditionally always a lama. Then the request must be made by the lama to the artist and only then can the work be created by the artist. A diligent artist will ceaselessly repeat the appropriate mantra, set out in the Buddhist shastras, whilst he works on the thangka. In this way the creation of a thangka is more than just work, it is an act of worship. And not only does the artist’s conduct during his work come under scrutiny in the thangka tradition but his entire life must be led in accordance with the dharma, a principle which is reflected in the complex psychological symbolism contained within the work. It was during this time too that Dorjee immersed himself in the long history of the art form. He relates to me the legend of the first thangka painting which was a gift from one Indian king to another during the time of Siddhartha Gautama, the historical Buddha. An artist was dispatched to Lord Buddha in order to render his likeness but when confronted with the task of painting him the artist was overawed by his presence and forced to avert his eyes. Lord Buddha, noticing the artist’s predicament, helpfully went and sat down next to a pond, thereby allowing the artist to paint him by tracing his reflection from the water’s surface.

Warming to the theme of art history, Dorjee goes on to explain the etymology of one word for art in colloquial Tibetan, ‘rimo’. Legend has it that a shepherd called Akar was grazing his goats far away from his home. One day, as he was watching over his goats, a dazzling rainbow formed in the sky and under the arc of the rainbow there appeared the most beautiful girl he had ever seen. Akar began to chase after the girl but the more he chased after her, the further away she fled until she eventually disappeared. In order to preserve her likeness in his mind Akar engraved an image of her on the smooth surface of a stone. When he returned to his village people asked Akar what the engraving on the stone was and he would reply with the words ‘ri pu-mo’ which mean ‘the mountain girl’. As news traveled of this beautiful artifact, Akar’s original words became muddled and people began to refer to the stone as ‘rimo’. It is interesting to note that like Saraswati, Hinduism’s goddess of knowledge and the arts, and the nine muses of Greek mythology, the original inspiration of the mythical ur-artist of Tibet is also female. Finally, Dorjee talks about the historical genesis of representational art in Tibet, its very earliest prehistoric origins. He reflects that these origins were almost certainly shamanic and animistic in nature and probably took the form of animals molded from dough which would have been used ritualistically in lieu of proper, live, animal sacrifices.

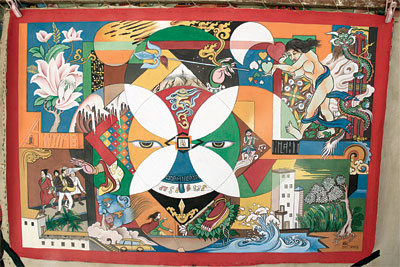

After two years of working exclusively under his thangka painting guru Palden, Dorjee was introduced to the famous artist Tenzin Norbu Lama from Dolpo. Unlike Dorjee, Tenzin Norbu hails from a long line of artists dating back over 400 years. He was trained in traditional thangka techniques before developing his own modern style of painting which has won him global renown. Becoming one of only a handful of Tenzin Norbu’s chelas or students was a pivotal moment in Dorjee’s artistic career and one for which he is very grateful. Asked why he thinks Tenzin Norbu selected him, Dorjee modestly supposes that their similar backgrounds and the tradition of a close relationship between the lamas of Dolpo and Mugu districts both played a key role. It seems to me that the guru’s recognition of talent and commitment in the young Dorjee would have been equally instrumental in his decision making process. Under Tenzin Norbu’s tutelage Dorjee was actively encouraged to develop his own modern style, which, while drawing heavily on traditional techniques, sets him free to experiment and innovate. As Dorjee puts it, in the modern style you are no longer confined by rules. Instead, the imagination becomes paramount but it is an imagination which has been schooled in the meticulous discipline of thangka painting. I ask Dorjee which he enjoys painting more, traditional thangka or his own modern style? His response is ambivalent; because of the importance of the dharma in his life, he is deeply devoted to thangka painting but he also admits, “Sometimes, I like to dance.”

And what I find out next is what happens when Dorjee allows his imagination to dance. He unravels several scrolls of recently completed work. They are like nothing I’ve seen before. A riotous mixture of pop cultural references, most notably Mickey Mouse, contend with traditional Buddhist motifs, Himalayan landscapes and calligraphic Tibetan script. There is Mickey Mouse sat in the lotus position in front of a fascinatingly intricate Potala palace on the left and the gleaming spires of the Petronas towers on the right. In another painting Mickey Mouse dances like Nataraj on the earth’s surface, surrounded by multicolored Tibetan mantras and occasional English words. Interspersed between these highly idiosyncratic works are some wonderfully ornate and detailed thangkas which clearly do follow all the painstaking rules we have been discussing. In one heavily gold leafed thangka Lord Buddha sits under a bodhi tree and accepts a luminous mango which has been proffered to him by a jungle monkey. It seems amazing, almost a paradox, that a single artist can at the same time produce such strikingly original creations and also such highly accomplished stylized compositions.