The Begum of Oudh is Indulged…

Recent and Historic Episodes in India and Nepal

Only in India could you find a long-running struggle with such faintly comic overtones. The Begum is indulged... (James Miles, Los Angeles Times, June 1985)

This story begs the question: Who was the Begum of Oudh? There seems to have been two of them (sort of), a little over one century apart. Which one was for real, or were they both?

Our story begins and ends in Delhi in the late 20th century with the so-called Begum Wilayat Mahal of Oudh, who claimed direct matrilineal descent from the historic 19th century Begum Hazrat Mahal of Oudh.

Along the way, Wilayat Mahal, the controversial and self-proclaimed 19th century Begum, lived for a decade or so in the Delhi railroad station, and later at the run-down Malcha Mahal on the outskirts of India’s capital city. No matter if she was legit or a fraud, her story shows how the sometimes imperious style of South Asian grandees can take on strange, tragicomic forms of indulgence.

The historic and unquestionably legitimate Begum Hazrat Mahal of Oudh was fourth wife of Wajid Ali Shah, the Nawab of Oudh from 1847 to 1856. She was highly praised at the time and is remembered today as a dynamic strategist and battlefield heroine in India’s 1857-58 First War of Independence (aka Sepoy Rebellion), when she seriously challenged the East India Company’s high-handed takeover of the Kingdom of Oudh. After being defeated by the British, she fled with her son Birjis Qadr, heir to the Nawab’s throne, to safe haven in Nepal where she was given sanctuary by Maharaj Jang Bahadur Rana. She died and was buried in Kathmandu in 1879.

sidebar:

Old Oudh

Oudh (Awadh, Avadh), once covered much of north India and has been described India’s wealthiest pre-colonial kingdom. Back then, some parts of far west Nepal, including Nepalganj, and Tulsipur in the Dang Valley, fell within its territory. Many Awadhi speakers still reside in the western Nepal Terai.

The House of Oudh was founded during Mughal times, in 1722 AD, by the first Nawab of Oudh, Sa’adat Ali Khan who reigned until 1739. The capital was at Faizabad on the outskirts of Ayodhya, a religious site sacred to both Hindus and Muslims. Later, under the fourth Nawab, Asaf-ud-daula (r.1775-97), the capital was moved to Lucknow. In time, a colonial British Resident was also posted there (just as one was posted to Kathmandu during the 1800s and for the first half of the 1900s). Faizabad, Ayodhya, and Lucknow, all in today’s Uttar Pradesh state, are barely 100 miles south of western Nepal.

Oudh was the garden and granary of India. But in 1856, 134 years after its founding, the tenth and last Nawab, Wajid Ali Shah (r.1847-1856), ran afoul of the East India Company and was summarily deposed. The East India Company’s excuse for taking over the whole of Oudh and controlling its’ vast wealth was based on the somewhat dubious grounds of the last Nawab’s ineffective rule and general lawlessness, and (true enough) his conspicuous debauchery. To be fair, however, after Wajid Ali Shah became Nawab he exercised little power or control, since the British had already assumed much of the kingdom’s administration in an 1801 treaty. Wajid Ali Shah is remembered today as a great poet and writer, and a magnanimous patron of music, drama and dance.

After he was deposed, the ex-Nawab with some family members and an entourage of servants, was given asylum in Calcutta where he was amply pensioned off by the British and lived resplendent luxury until his death in 1887.

His fourth wife Begam Hazrat Mahal stayed back in Lucknow, however, and starting in 1857 she led thousands of followers in a powerful attempt to repossess the former kingdom. Her ambition and the respect of the locals so annoyed the colonial authorities that they tightened their defenses and ultimately put down the rebellion in 1858.

To help supress the Lucknow uprising, Nepal’s then Maharaj Jang Bahadur Rana sent troops to aid the British. After the city was secured, soldiers rampaged through the streets making off with the spoils of war. According to one historian, the British authorities were “appalled by the wanton destruction and lust for gold on all sides... Soldiers staggered out of houses laden with ‘shawls, rich tapestry, gold and silver brocade, caskets of jewels, arms, splendid dresses’; and beautiful china, glass and jade were all ‘dashed to pieces’. The undisciplined behaviour was by no means confined to the Nepalese troops, but [they] took their share of the plunder—and created a resentment that smoulders to this day.” It has been reported that the “Lucknow Loot” destines for Nepal filled 4,000 bullock carts.

Another Nepal connection in this story involved the illustrious Peshwa Nana Sahib, who led the mutinous uprising against the British at Cawnpore (Kanpur), south of Lucknow. There, both sides committed bloody massacres and suffered horrendous military and civilian losses. In defeat, Nana Sahib escaped into western Nepal. What happened him then is pure speculation. By one account he was killed by a tiger during a hunt in 1859. By another account he died of fever in 1860. Or, did he flee on to Gujarat, where he died in 1903? Or did he return to live incognito somewhere outside of Lucknow until his death in 1906? Or…? No one scenario is rock solid, and none has been formally accepted as true?only that he disappeared within a few years of reaching relative safety in Nepal.

Today, Nana Sahib is considered a hero of India’s First War of Independence. Many poems, books and a film have been produced about his legendary life.

Delhi Station

More recently in the early 1970s, over a century after those momentous events, another legend (of a sort) burst unexpectedly into the news—a self-proclaimed modern Begum of Oudh.

She called herself Wilayat Mahal, and claimed maternal descent from the historic Begum Hazrat Mahal of Oudh, wife of the deposed Nawab of Oudh. For some time Wilayat (Vilayat) had petitioned the Indian government in Delhi and the British government in London for compensation due to her as a high-ranking scion of the House of Oudh. She specifically demanded that the Farhat Bakhsh Palace in Lucknow be returned to her as rightful heir.

As that was not possible (by then, the palace had been converted for government use), Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru reportedly gave her a house in Kashmir. After it burned down in 1971, however, she traveled to Delhi to pressure the government into giving her something better. While transiting Delhi Station, the homeless Begum Wilayat camped out on a railroad platform for a while, then commandeered the V.I.P. lounge where she lived for over a decade with her son Prince Cyrus Riaz (aka Ali Risa), her daughter Princess Sakina, their Nepalese servants, and a pack of dogs for protection. And there, in Delhi Station, the Begum Wilayat remained immoveable, while seeking the reparations she demanded.

Over time the railway authorities tried unsuccessfully to expel ‘Her Highness.’ When persuasion got nowhere, they cut the electricity, shot some of the dogs and (according to one writer) “even turned a garden hose on the royal family.” Nothing worked. It was speculated that “As a powerful figure in the Shiite sect of Islam, the Begum is lionized by India’s Muslim minority as a symbol of resistance to the Hindu-dominated government.”

It was also said that “Her habit of commandeering the second-class ladies’ rest room for a three-hour bath every day infuriate[d] the commoners queued up outside.”

A Bleak Life

In 1984 Begum Wilayat Mahal’s plight attracted the sympathetic attention of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, who offered her a long-abandoned, falling-down, bat-infested old palace called Malcha Mahal on the eastern outskirts of Delhi. It had originally been built as a large ‘shikaargaah’, a hunting lodge, in the 14th century, by Firuz Shah Tughlak, Sultan of Delhi. After Indira Gandhi was assassinated on October 31, 1984, Malcha Mahal was still available but the promised repairs were ignored by government authorities.

In 1985 the Begum moved in anyway, despite bats and pigeons, snakes and scorpions, a leaky roof, and no doors, windows, running water or electricity.

Malcha Mahal is located on an uninhabited jungle ridge not far from Rashtrapati Bhavan, the Indian President’s House, and even closer to the hi-tech Delhi Earth Station. If you risk approaching Malcha Mahal you’ll likely see exotic birds and a few wild critters scuttling through the undergrowth. Come too close and you’ll be met by the snarling dogs and this bold sign:

Entry Restricted

Cautious Of Hound Dogs

Proclamation

Intruders Shall Be Gundown

In recent years, Malcha Mahal has become famously known as one of India’s most mysterious and haunted places. Some jokingly call the old palace “Wilayat Mahal.”

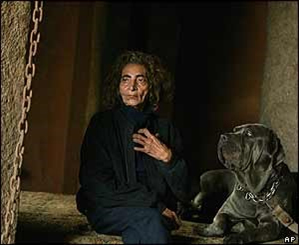

From 1985 on, the lives of the Begum and her son and daughter became increasingly reclusive, desolate and strange, a grim, dark and secluded existence without modern amenities. Malcha Mahal stands (falling down) in stark contrast to the state-of-the-art telecom facilities next door, described by one observer as “bristling with modernity, large dishes, CCTV and high-security defenses.” Wilayat’s small family and a few Nepali servants inhabit the old palace along with “a retinue of 13 ferocious dogs,” according to Barry Bearak, author of a 1998 article in the New York Times. Over time they kept Doberman Pinschers, German Shepherds, Labrador Retrievers, and big Neapolitan Hounds.

“One night,” Bearak writes, “intruders poisoned seven of the watchdogs and made off with antique bowls and silver goblets kept on an ornately set table.”

After that, Princess Sakina said of her mother: “The death of our animals made it hard for Her Highness to bear the unbearableness. So much is unbearable.”

Occasionally, Prince Riaz has been seen out on an old bicycle buying provisions and dog food, all apparently paid for by selling off jewels and other possessions. The Begum, meanwhile, remained secluded, reportedly reading the Koran and attending to her prayers—until, that is, the day she committed suicide.

On October 12, 1993, the 62 year old Begum Wilayat of Oudh swallowed the ‘Drink of Silence’, a lethal concoction of crushed diamonds and pearls washed down with a dose of poison. By one account, possibly exaggerated, her body lay sprawled across her writing desk for ten days before she was buried. Perhaps even more of an exaggeration, it is also said that the prince and princess slept beside the decomposing her body for at least one night before attempting to embalm her (too late) and bury her in a simple grave.

At first a tombstone with her name on it marked the site, but after a year, in fear of grave-robbers, the decomposed body was disinterred and a funeral pyre was prepared. However, as Princess Sakina pointedly told the Times reporter, her mother was not ‘cremated’?that term “is too common,” she said. “What we did was confer Her Highness to the pious flame.” The ashes were later spread on rivers in the former Kingdom of Oudh.

Over the years only a few journalists and photographers have been allowed to glimpse the prince and princess’s stranger-than-life existence. A photo of Princess Sakina, taken after her mother’s death, shows a haggard woman clad in a black cape, with disheveled hair, vacant eyes, and deep lines of age and despair on her face. A photographer she met quotes her as saying, “We have been left in darkness.” She told the Times reporter that “Cruel nature takes malicious delight in our ruin, so I desire nothing, want nothing. We are now the dynasty of the living dead.”

Since then there have been rumors that Princess Sakina died. But by recent accounts the prince and princess were still alive in mid-2016, at home in Malcha Mahal. Since then, not much more is known, as entry to Macha Mahal is prohibited. Thus, the final story of the life and death of the Begum and her family has yet to be written. In the meantime, while all this was playing out, her story drew a serious challenge.

Counter Claims

In 1975 and again in 1985, when Wilayat Mahal’s story was in the news, another claimant to the Oudh estate came forth to dispute her assertions and question her authenticity. Anjum Quder (Qadr), identifying himself as “the present head of the ex-royal family of Oudh,” wrote from his home in Calcutta urging Indian government authorities to put a stop to the woman imposter. Anjum identified himself as the great-grandson of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah and Hazrat Mahal through their son, his grandfather, Birjis Qadr (b.1845).

In a letter dated April 4, 1975, Anjum Quder addressed the issue to a member of the Vidhan Sabha, lower house of the state assembly in Lucknow. “We the members of the House of Avadh,” he wrote, “were surprised to read in a Calcutta news-paper to-day of your adjournment motion in the Vidhan Sabha to sympathize with a lady you named Begum Vilayat Mahal, who seems to claim that she was the great granddaughter of queen Hazrat Mahal, I am constrained to inform you that the claim is a hoax, and the lady is unfortunately impersonating.”

Quder pointed out that because Begum Hazrat Mahal had only one child, a son, no one can claim direct matrilineal descent from her. In his letter, he names Birjis Qadr as the legitimate royal successor to Nawab Wajid Ali Shah. He also names some other closely related progeny, but there is no Princess Vilayat on the list.

Furthermore, Quder wrote, the “Fraud of the present claimant is obvious from her very name ‘Begum Vilayat Mahal’ because Mahal is not really an inheritable work. Mahal is a title which used to be awarded by a Muslim King or Emperor in India to his wife after she bore him a son.” Only after Anjum Quder’s great grandmother bore Wajid Ali Shah a son was she entitled to the use the term ‘Mahal’?as Begum Hazrat Mahal. But “No daughter of a Mahal can be named a Mahal, much less a great granddaughter. This title comes from a husband king.”

“Evidently,” he concluded, “the name Begum Vilayat Mahal has been coined by a not so clever designing person or persons just to rhyme with Begum Hazrat Mahal, in order to gain cheap publicity and earn a fast buck.”

Anjum Quder’s second letter, dated July 25, 1985, went to the Prime Minister about the time that Begum Wilayat was moving to Malcha Mahal. In it, he reiterates that her name is nowhere recorded in the family genealogy and that she has no past history of more than about 15 years since she invented her story. She may be “a convent educated Kashmiri lady,” he says, but she seems not to have “perfected the traditions and culture of ancient Indian Muslim royal households, in spite of efforts.”

The exceedingly wealthy Nawab Wajid Ali Shah had scores of children from many of his 359 wives, so you can imagine that members of succeeding generations engaged in contentious struggles and factious fighting over who among them were legitimate heirs. Somewhere buried in the confusion there may be a thread of truth about Wilayat Mahal’s as yet unresolved claims. Maybe…, maybe not.

But, that’s not the end of the saga, for the backstory detailing the scattering of descendants of the House of Oudh reveals more mishmash, and more Oudh-Nepal connections.

Safe Haven in Nepal

After the ex-Nawab Wajid Ali Shah departed Lucknow in 1857 for his amply pensioned retirement in Calcutta, his wife Begum Hazrat Mahal with their son Birjis Qadr and many followers stayed back in Lucknow to pursue armed resistance against the British. On July 15, the 12-year old boy was pronounced as new Nawab and on August 6, Bahadur Shah Zahar, the last (figurehead) Mughal Emperor of Delhi, issued a vague declaration giving him the more exalted title of King of Oudh. The boy was formally crowned, with his mother as regent. The following year, however, the British dashed their attempt to resurrect the House of Oudh. Upon her defeat as leader of the Lucknow rebellion, Begum Hazrat Mahal turned down a British offer of amnesty and a pension, and defiantly set off toward Nepal seeking sanctuary. After negotiations with Maharaj Jang Bahadur Rana, she was allowed to settle in Nepal for a price?paid for with some of the jewels and heirlooms that the Begum carried with her.

At first the Begum lived in the Kathmandu house that had once belonged to Bhimsen Thapa, a former Mukhtiyar (Prime Minister) of Nepal and uncle to Jang Bahadur. Later, she built her own home, plus a mosque and her imambara (burial shrine), in which she was interred in 1879. Her grave in central Kathmandu at Kamaladi is still cared for.

Ironically, it was her benefactor Jang Bahadur who had sent Nepalese troops to help the British put down the very rebellion in Lucknow that Hazrat Mahal had led. But because serving the British was clearly in the greater interest of Nepal, this contradiction was conveniently ignored so as not to interfere with the Maharaja’s broader diplomatic goal of ensuring Nepal’s independence as an ally of the British in India. In the meantime, East India Company rule was replaced by the British crown in 1858, which put India under direct rule of the Raj.

Today, Begum Hazrat Mahal, like Cawnpore’s Peshwa Nana Sahib, is revered as a hero of India’s First War of Independence, complete with poetry, books and a film about her.

Meanwhile, Birjis Qadr grew up in Kathmandu and eventually married a granddaughter of the last Emperor of Delhi, Bahadur Shah Zahar. Bahadur Shah traced his ancestry as the son of Emperor Akbar II, all the way back to Tamerlane who had laid the foundation of the Mughal Empire in central Asia during the 14th century.

A Fatal Repast

After the death of Hazrat Mahal in 1879 and of Wajid Ali Shah in 1887, Birjis Qadr moved from Kathmandu to join other extended family members in Calcutta. As historian Amritlal Nagar has described it, Qadr “badly wanted to return to his land … fed up with his strained circumstances and increasing alienation” suffered in Nepal. At Calcutta he hoped to claim some of the government pension due him as the eldest surviving son and heir of Wajid Ali Shah. He needed it to look after members of the family and their many dependents and retainers, said to have been as high as 20,000 people.

At the time, Qadr’s immediate family included his pregnant wife Mahatab Ara, and three children (two daughters and a young son). One evening, not long after arriving in Calcutta, they were invited to dine with one of the relatives. Birjis attended the banquet with his son and eldest daughter, but due to her pregnancy Mahatab Ara stayed back, along with the youngest daughter. Going to that dinner party “was a foolish move,” writes Amritlal Nagar, for “Soon after partaking of the meal, they all died, possibly poisoned.” And though the hosts sent the Mahatab Ara Begum a platter, she “refused to eat the heavily spiced meal and so did her daughter. They were the only survivors.” In death, Birjis Qadr was 47 years old.

On official documents, Birjis Qadr’s death was inexplicitly registered as “fever,” but the descendants are convinced to this day that he was “killed mysteriously by envious begums and siblings.” As Shailvee Sharda has reported in the Times of India, Lucknow edition of May 30, 2016, “Besides the legacy of valour and courage, the Qadr family has inherited sibling rivalry too.”

A few months later, a second son was posthumously born to Birjis Qadr, thus retaining the paternal line. After that close call, however, his mother took great care with whom she and her remaining children, especially her son, dined.

On the Begums’ Character

Back in 1985, when reporter James Miles of the New York Times met Begum Wilayat at Malcha Mahal, ‘Her Highness’ summed up the royal temperament. Speaking through Prince Riaz and using the imperial ‘We’, she said:

“We don’t make requests, we make demands.

We don’t fight with power, we fight with character.”

Regardless who Wilayat Mahal really was and what drove her to make the demands that she did, and despite how her particular legend has been interpreted or mocked, we are still have the more certain and historic legacy of the Begum Hazrat Mahal to admire. Her grand wish was to restore the Kingdom of Oudh, and although her power was insufficient to achieve it, her strong character lives on in legend, including her burial site in downtown Kathmandu.

It can certainly be said that both Begums were indulged…

———————————————————

Author’s Note. What a story! But putting it together from multiple and often conflicting sources has been a challenge. Readers beware, for what is written here includes the sorts of tales that foster exagerated headlines when retold by thrill-mongers on dubious social websites. I’ve read many of them and have been bewildered by some remarkably shoddy journalism, including incorrect names, dates, photos, and hyped-up story telling. For example, Begum Wilayat’s suicide is variously said to have been in 1985, in two wrong months of 1993, and as far off base as December 2008. Her suicide was on October 12, 1993.

For this article, I have taken pains to rely primarily on the work of reputable Indian and international journalists, especially those who have actually met Wilayat Mahal and/or her children, or who have interviewed the living descendants of Birjis Qadr. Comments on this story are welcome, and a more complete list of sources is available by request to the author at don.editor@gmail.com.

PHOTOS – ALL IN THE PUBLIC DOMAIN EXCEPT AS ATTRIBUTED.

Most can be retrieved from Bing and Google Images.

.jpg) |

|

The last Nawab of Oudh, Wajid Ali Shah Wajid Ali Shah in his old age

.jpg) |

|

Birjis Qadr, son of Wajid Ali Shah Birjis Qadr in his youth

and Begum Hazrat Mahal

Princess Sakina and hound. Credit: watchmyphotography.blogspot.com

Bahadur Shah Zafar, the last (figurehead) Mughal Emperor of India