Objects of old become Proustian portals to a time that has all but come to pass.

Memories have a strange power over people. There is no telling what seeps in and what gets filtered out. What you cling on to, and what you let go. And suddenly, years later you find yourself under some other skies, reminiscing over sights and sounds that you had thought were long forgotten.

We are living in a momentous time, New traditions are being crafted, new objects gaining relevance, and new memories are being forged. It is times like these that the power objects of bygone days become ever more relevant— each a portal that takes us back to cherished memories of younger brighter days and harken back to lifestyles that are all but lost to the slippery sands of time.

With that in mind, we gave our collaborators a license to roam the foggy realms of their memories and pick out objects that transport them to another time and place. If for nothing than to afford them one last parting glance.

This beautiful collage of reverie and nostalgia emerged.

Glass Treasures

Text: Kapil Bisht

In the years from when I was nine or ten until I was twelve, I was obsessed with marbles. I set out from home every morning with a bulge in my pant pockets. The bulge would be the dozens of marbles I was carrying. As I descended the slightly steep path to my friend’s house, I would hitch my pants, which had dropped an inch or two under the marbles’ weight. Then we would begin our marble games. If I executed my strategies well, I would return home in the evening with a larger bulge in my pockets.

The glass globes were at the center of my universe during those years. I would regularly clean them, count them, study them for defects (I would play with the worn and damaged ones and stow the shiny ones) and store them according to size, color and pattern.

Whenever I could I went to the shop down the road to check out the “new arrivals.” The shop was more accurately a khoka, a small wooden structure on stilt-like legs. The shopkeeper would always let me empty out his jar of marbles and pick the ones I liked. A rupee got fifteen marbles, and every khoka displayed a jar of glistening marbles next to the best-selling toffees and candies. They were that popular. I was a shopaholic when it came to marbles. I also bartered with friends and rivals.

I don’t see marbles in jars in shops anymore (or maybe I no longer notice). Perhaps they keep them in some corner at the back. I guess marbles don’t mean as much to kids as they used to when I was a kid. I used to prize my marble collection like it was a treasure. I knew individual marbles in the collection: the pattern inside one looked like a cat’s eye, another contained a blue wispy cloud. You get a similar kind of joy looking at a screen now, I guess. Flicking a screen is a kid’s thing now, not shooting marbles all day till you got a coat of mud and calluses on your fingers.

Sticks and Stones

Text: Sanjit bhakta pradhananga

I grew up amidst the narrow gallies and crumbling chowks of Asan. It was a time of innocence and simplicity. A time before Scooby Doo and Super Mario; when a dirty bicycle tire and a tiny stick were enough reasons to spend an entire day frolicking outside. We grew up in tiny homes and large extended families, in the squalor of tightly-knit communities.

Every community had their own army of rugrats, connected by an intricate network of windows and rooftops and a singular desire to spend every feasible second away from home and homework. It was a time before Instant Messaging or even doorbells. A simple ‘Oie’ ringing from the courtyard below was enough to perk up ears and grab our attention. Within minutes of the first call, an entire congregation gathered and another round of evening street games commenced.

Every community had their own army of rugrats, connected by an intricate network of windows and rooftops and a singular desire to spend every feasible second away from home and homework. It was a time before Instant Messaging or even doorbells. A simple ‘Oie’ ringing from the courtyard below was enough to perk up ears and grab our attention. Within minutes of the first call, an entire congregation gathered and another round of evening street games commenced.

The favorite of which was ‘seven stones’ – a popular game of improvised dodge-ball that is known by different names across the breadth of South East Asia. It was a simple concept. All one needed was seven flat stones stacked on top of each other, a tennis ball ( sometimes just socks hastily wrapped into a bundle) and two teams pitted against each other. One team knocked down the column of stones with the ball and fanned out across the courtyard, making strategic darts back to the center to reassemble the stones. The other team defended the pile and tried to hit opposing players with the ball which disqualified them for the round. The attacking team won if they were able to build back the column before all members were disqualified. If the defending team tagged all of the opposition, the teams switched places and the defenders got the chance to attack the stones.

Looking back now from a jangle of innumerable techie distractions it is amazing how a simple stack of stones and a ball kept a rowdy bunch of young kids engaged with hours upon hours of pure exhilarating fun. Week after week, year after year the game sustained its inexplicable charm as we bruised our limbs and skinned our knees and forged camaraderie that would last long after we’d grown up and such games could no longer feature in our busy schedules.

On a recent visit to the same old narrow gallies and crumbling chowks I was taken aback by the haunting silence that has now settled upon that once bustling neighborhood. Where have all the kids gone? Where is the unbridled ruckus? The life that once echoed into the shivering dusk.

All that remains are the stains on the walls from our dodge-ball games, broken windows and memories cast to last a lifetime.

Those were simpler days.

The Wheel Spins On

Text: Sanjit bhakta Pradhananga

Every now and then, I spot a wayward bicycle tire lying orphaned amidst the pot-holed streets of our busy city. With chakka-jams and plumes of rubbery smoke thankfully receding into memory, it seems these abandoned tires have little use left in this world. Occasionally, I get a nagging urge to pick it up and relive the days when finding such a tire would be akin to a discovering a treasure trove. Back then the only thing “gross” about picking up a mud-caked bicycle tire from the streets would be the idea that in 20 years I couldn’t bring the adult me to do it anymore.

The child in me chides me in disappointment.

The child in me chides me in disappointment.

That child, by the time he was six, had a burgeoning collection of these abandoned tires. I would hide them meticulously in the dark and dungeony duck pen we had at our house, away from the prying eyes of cousins and a disapproving mother. At every opportunity, I wheeled out a dirty tire (now splattered with duck shit as well) for an absolute joyride.

It was simple and innocent fun. I would roll the tire upright and guide it with a small stick and invent games for myself.

How long could I go before it toppled over? What obstacles could I pass it through? How fast could I go, or how painstakingly slow? That tire shaped round like emptiness was a wellspring of infinite possibilities.

The favorite adventure, however, was taking the tire for a spin into the outside world. Ducking from people, dogs and motorbikes I navigated the wheel through the bustling streets of Asan, going from tolle (community) to tolle. From Balkumari, to Nyakantala, to Seagal, to Jyatha, through the muddy streets of Tyauda and back to Balkumari. Then all over again. Often at bahals and crossroads, I’d run into other fellow drivers tracing a route of their own and it would mean only one thing. A race was on. Sizing up each other and revving engines in our minds, we darted fast and furiously into the crowd, bouncing like pin balls towards an undesignated finish line.

Nobody knew what “winning” was, and no one cared. We rolled our tires to roll our tires.

Years later, every time I see a Zen Enso, I’m reminded of those wheels.

Every time, I see an abandoned tire, I am reminded of a Zen Childhood.

And duck shit.

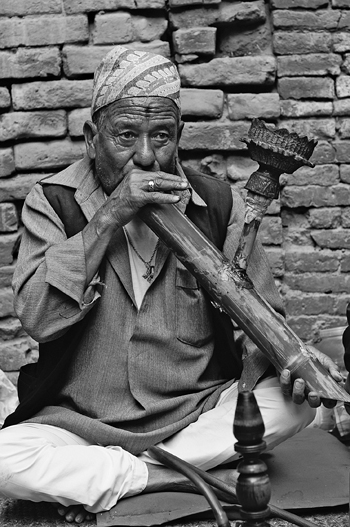

Tamakhu Tales

Text: Rajendra Balami

I don’t remember a time at my maternal grandparents’ home before bijuli (electricity) came to Khaireni – although, surely, there must have been such a time, because I remember Bhim Bahadur kaka in our kitchen, a kilometer to the west, screwing in a light-bulb that glowed very bright – too, too bright for it to remain true – and seared its jagged fire in my eyeballs before going out, kapftt. But, I don’t have memories of my grandfather Lila Bahadur Hajurb? and the dark Khaireni nights without bijuli, without the too-bright tube-light he had put outside his house. Hajurb?’s friends came from different directions – Sainla Jeeba from the west, Kandel Jeeba from the south, Kalkattey from the east, and to guide them to his pindhi (patio), Hajurb?’s too-bright tube-light lit the aangan (courtyard), the mangoes and guavas around the aangan and the mustard field, all the way to the Kavra tree, and the aali ko bato (village tracks) in the paddies beyond the Kavra. When the friends reached Hajurb?’s aangan, they washed their feet under the hand-pump and sat on the radi blanket on the pindhi. Ama brought out the hookah, patted into place the sweetly fragrant, sticky tamakhu (hookah) on the coconut shell atop the carved stem and placed a few glowing embers on it. Hajurb? often gave the hookah to Kandel Jeeba to light, because, although childhood friends and contemporaries, Kandel Jeeba was Hajurb?’s grand-uncle by relation – making me an astounded khanati (great-grandchild) in attendance, watching the old men smoke, bewitched by the scent of whole tobacco leaves cured in homemade molasses. Then they told hunting stories, or stories about how Kandel Jeeba once refused the help of six men and carried an entire agrakh log home by himself, or how much ghee they could eat in their youths, or of the men from lesser families who had worked alongside them, only to be eaten by a tiger, or fall off a cliff in a drunken stupor, or die after vomiting blood for two days, without any outward cause. They laughed, and they cried – did they spice their tamakhu with herbs I wasn’t aware of as a child?

In the morning, I’d go behind the house to touch the dew on the silky hairs on the tobacco leaves in Hajurb?’s personal patch. Sometimes he would be there, too – picking and throwing away pests, drawing a ring of dry ash around the base of each plant to keep away insects. Behind the tobacco patch was another field full of sugarcanes. Sometime in the cold months, the canes were pressed and their juice boiled in large copper cauldrons until the molasses khudo turned dark and thick, and then let to cool in deep copper gagris, where rock-sugar misri crystallized at the mouth and upon becoming dry, the thick syrup khudo became sakhkhar, or chaku. The tobacco and the sugarcanes were Hajurb?’s preoccupation – they were the centerpiece to his evenings. The old men spent hours chatting about this and that, until the too-bright tube-light was smothered under moth-wings and the midnight hour approached. They are all gone, those old men – and with them the culture of cultivating your own tobacco and sugarcanes to prepare your own tamakhu. Now I see friends with cigarette stained teeth, oftentimes solitarily brooding in a corner, or hurriedly sharing a cigarette before being shooed back into their offices, and I feel sad. I think Hajurb? would disagree with tobacco, and ask to be given a hookah of his mild, sweet, wet tamakhu.

In the morning, I’d go behind the house to touch the dew on the silky hairs on the tobacco leaves in Hajurb?’s personal patch. Sometimes he would be there, too – picking and throwing away pests, drawing a ring of dry ash around the base of each plant to keep away insects. Behind the tobacco patch was another field full of sugarcanes. Sometime in the cold months, the canes were pressed and their juice boiled in large copper cauldrons until the molasses khudo turned dark and thick, and then let to cool in deep copper gagris, where rock-sugar misri crystallized at the mouth and upon becoming dry, the thick syrup khudo became sakhkhar, or chaku. The tobacco and the sugarcanes were Hajurb?’s preoccupation – they were the centerpiece to his evenings. The old men spent hours chatting about this and that, until the too-bright tube-light was smothered under moth-wings and the midnight hour approached. They are all gone, those old men – and with them the culture of cultivating your own tobacco and sugarcanes to prepare your own tamakhu. Now I see friends with cigarette stained teeth, oftentimes solitarily brooding in a corner, or hurriedly sharing a cigarette before being shooed back into their offices, and I feel sad. I think Hajurb? would disagree with tobacco, and ask to be given a hookah of his mild, sweet, wet tamakhu.

Tokens of Love: Chiniyum kisi

Text: Srizu Bajracharya

It was always easy to find a hiding place in Makhan Bal ; the dhukuti (granary) inside my great grandfather’s house was one of my favorite hideouts when my cousin counted 10. I used to run down the wooden staircase playing choyii duum (playing tag) as my maijus and aunties struggled to ship batahs (buckets) full of chweyla and baji (beaten rice) for the family gathering downstairs. Makhan Bal was where I came to as a child, holding onto my mom’s hand tightly because I was afraid of the dark corridors in my great grandfather’s house. I wouldn’t dare venture out alone because for some reason the little me found the old house eerie. But it was here, where my mom grew up listening to great grandmother’s stories. It was where the younger her had hung bells of chiniyum kisi that her mamas used to gift her during Tihar.

The first time she recounted her story of chiniyum kisis to me, I grappled the unfamiliarity of the two different times we were from. I had no idea about what she was describing to me. Even then her eyes had glistened with joy as she tried to draw me a picture of the chinyum kisi that she missed because of the little memories she had clung on to through time. Chiniyum kisi, in the olden days was a sugar candy that came to the market every Tihar in different colors especially in pink bearing a shape of Laxmi.

The first time she recounted her story of chiniyum kisis to me, I grappled the unfamiliarity of the two different times we were from. I had no idea about what she was describing to me. Even then her eyes had glistened with joy as she tried to draw me a picture of the chinyum kisi that she missed because of the little memories she had clung on to through time. Chiniyum kisi, in the olden days was a sugar candy that came to the market every Tihar in different colors especially in pink bearing a shape of Laxmi.

The younger her made attempts to tie her sugar candies to the windows of her room in Makhan Bal as the world below her bustled to their homes in the narrow alley during Laxmi Puja. There were times when her aunts teased her saying “kah! Changu kisi ta la bhujicha na nebila, aah cha: chu yafu?” (The fly ate your sweet; what will you do now?) when flies would rest on her dangling colorful sugar lumps. But she never stopped hanging her chiniya kisis in the windows. She was always showered with sugar treats from her mamas in Tihar because she lived away from her home. My mama bajes (grand uncles) used to call out to her to give her chiniyum kisis that were shaped as flowers, elephants and horses and as she would reach out with her tiny hands they would hide the kisi behind their back.

“It was just colored sugar but we licked it happily, we didn’t cry for Cadbury” she had said smirking at me. On Mha Pujas her cousins fought for their chance to decorate their mandap with chiniyum kisis. Her eyes filled with tears if she didn’t get the big fat pink chiniyum kisi for her own. On the Makhan staircase, my mother and her dozens of cousin sisters licked their yellow, pink, green sugar sticks. They would stick out their tongues to show their green and pink tongues to the peddlers.

It’s hard to imagine now, how 30 years ago chiniyum kisis decorated trunks where Goddess Laxmi was worshipped. They say the flea markets in Maru, Ason and Makhan were filled with a mass stock of colorful chiniyum kisis besides palchas (terracota oil lamps) and masala pwas (packet of dry fruits). But I will never be able to treasure that joy that my mom felt. Time I guess just vaporizes before our eyes and only those who have lived those days will remember those tokens of love: the bliss of owning a sugared miniature of Laxmi, elephants and horses as chiniyum kisis.

Knots

Text: Utsav Shakya

I remember winter in Kathmandu as somehow being colder, when I was a young boy. Perhaps it’s the memory of driving into Kathmandu from Birgunj, listening to MaHa tapes in our blue Hyundai sedan. I’d feel the nip in the air around Naghdhunga, I think. Maybe that’s why the chill from those days has remained with me.

I was studying in Birgunj then, but we’d visit family in Kathmandu during my vacations. To prepare my sister and I for Kathmandu’s foggy winters, my mother would knit us chunky sweaters in the cosy living room of our Birgunj home.

Every day after our house in Birgunj grew quiet, my mother would take out the plastic bag with her ball of yarn and needles and sit down to knit. I’d prop up beside her on the sofa, watching her fingers move over and away from the needles, developing a rhythm as they wove beautiful patterns with the wool. No matter how many times she’d teach me how, I’d always forget the next time I’d try.

She’d knit with muscle memory; my mother could keep an eye on us, watch what was coming on Doordarshan, or help us with our homework without missing a single knot. As the ball of yarn got smaller, she’s ask us to stand up straight in front of her to check for size; I think we still have most of what she knit for us, in the family.

Decades after my mother knit me those sweaters, years after she taught me how and years after I forgot, my mother still teaches me new things every day. I haven’t seen knitting needles around the house in a long time now, but every time she sees a cardigan she knit, on a child in our family, her eyes light up as she announces how the wool in those days was so good, and how she could work tirelessly.

Red Feet

Text: Yukta Bajracharya

Tataju came home once in two weeks or every time there was a puja going on, to trim toe-nails and purify everyone.

Back then, I used to impatiently wait in line to get my feet painted red with allah, a red liquid that Tataju brought with her to paint the feet of women, after she was done trimming the nails. Being the youngest meant, I had to wait for all the elders in the family to be done with their turn. But most of the times I would linger around the terrace corner, where Tataju sat, legs folded and body bent closely towards a pair of feet, using her tools to trim toe nails and rub them against a special kind of stone to make them shine. Restless, I would sit and stand repeatedly, start twisting my hands and feet every which way I could, and would occasionally grunt or say ‘hyaaa’ until one of the grownups gave in to my dramatics and said “Kaka, maichita ni allah tayabyu” (“Let the little one have her turn.”) Being the small maicha of the household had its benefits.

I would sit on the sukul mat and place my feet in position for Tataju. My nails were too soft for Tataju’s tools, grownups told me. So I never got to have Tataju cut them. But as long as I got to wear allah, I did not mind. Tataju, would take out her small brush from an old leather pouch and dip it into the allah that was filled into a small camera-film-can. As Tataju held my feet into her hands, I would giggle. I would squint my eyes, giggling as Tataju applied the first stroke of allah, starting from the side of the big toe on my right foot and made the brushes way across all the five toes. By the time Tataju got to the next foot, I would get used to the brush and would no longer be giggling. I would follow the brush as it made gentle strokes on my skin, waiting for my feet to be transformed with the red paint.

“Make a circle here for me, Tataju,” I would request, pointing to the center of the top of my right foot. “And here too,” I would say pointing to the left foot.

“Ka,“ Tataju would say when she was finally done touching up the circles.

I would then get up and run to show off her feet to Nini and Mother.

“So pretty!” They would compliment.

Happy and smiling, I would run off to the courtyard to play with my friends and to show them my beautiful, freshly painted feet. Indeed, I did feel pretty and special. Keeping both feet together and looking down on them before stepping on to the hand-drawn hopscotch field, I would wish Tataju would come home every day.

25 Paisa Worth of Happiness

Text: Prabin Maharjan

When I was a kid, the only thing I could afford with my pocket money was an orange ball—the ubiquitously popular round orange flavored candy, wrapped in a golden plastic wrapper. Back then that was pure victory, a celebration, of sorts, of occasionally earning the mighty 25 paisa from my parents.

Later on, during school and early college days, everybody preferred the slightly peppery tasting ‘black balls’ rather than the orange variety with the change money after lunch. Everybody would be constantly chewing and sucking them with closed mouths for the rest of the afternoon. In the end the whole classroom floor would be covered with the wrappers, as everybody was careful not to make the crackling noise from the wrapper and wouldn’t even bother to place them back in the pockets afterwards. We were all just so addicted to the candy dessert. The price of the chocolates remained the same, 25 paisa was such leisure.

Later on, during school and early college days, everybody preferred the slightly peppery tasting ‘black balls’ rather than the orange variety with the change money after lunch. Everybody would be constantly chewing and sucking them with closed mouths for the rest of the afternoon. In the end the whole classroom floor would be covered with the wrappers, as everybody was careful not to make the crackling noise from the wrapper and wouldn’t even bother to place them back in the pockets afterwards. We were all just so addicted to the candy dessert. The price of the chocolates remained the same, 25 paisa was such leisure.

“Yo paisa ta chaldaina dai” (“This money doesn’t work anymore”), said a kid refusing to lay his hands on it when I showed him a rough but whitish 25 paisa coin lying astray on the road recently. Surprised and saddened I left, but realized that I haven’t had seen any of those orange balls or the black balls for many years. I’m wondering what else I can get with my 25 paisa these days.

Change is inevitable and necessary but it’s saddening to see the once mighty twenty five paisa, which once bought happiness for a lot of people like me lose its glory. Sadly it can hardly be seen around anymore. But the personal hunt for the orange ball and the happiness they brought, however, continue!