MaHa’s satires have been instrumental in bringing forth the commoner’s plights. It helps that they’re also the country’s most beloved actors.

Who is Dhruva Ram Pandit? He is a guileless simpleton who can’t tell a straight story. After he finished “being employed for the day,” he went home, washed his only pair of work clothes and set them out to dry overnight. He cooked, ate, cleaned up, woke up the next morning, cooked, ate, cleaned up and prepared to go to work.

But his clothes were still damp. It was already ten o’clock in the morning. Dhruva Ram was running late for his work as a proofreader at Gorkhapatra Sansthan, the nation’s only daily newspaper in Nepali, so he thought up a quick solution: iron his clothes dry, and then rush to work.

But his clothes were still damp. It was already ten o’clock in the morning. Dhruva Ram was running late for his work as a proofreader at Gorkhapatra Sansthan, the nation’s only daily newspaper in Nepali, so he thought up a quick solution: iron his clothes dry, and then rush to work.

As he was ironing his trousers, the electricity went off. Load-shedding: never too far from a Kathmandu day. His mind – as he boasted to himself – was something mercurial that morning. He pumped the kerosene stove into a hot roar, put a clean pot on the stove and stuffed it with his damp turtleneck. It felt strange to sit before a hot stove with something cooking in a pot and not take up a ladle to fold the turtleneck as if he were cooking a curry. So, he did – he stirred the turtleneck lovingly, as if he were sautéing two potatoes and half the length of a radish. Soon enough, the turtleneck was all done, nicely cooked and dry. Dhruva Ram was even more in awe of himself.

And he had cooked with such single-minded devotion to his morning’s ruse that he forgot all about the electricity, which had returned like a sulking, lovelorn son, slinking out of the house one moment without permission, and thieving back in just as quietly, as if to evade a mother’s wrath. When Dhruva Ram returned to his trousers, they were busily smoking – “Phoos, phoos, phoos!” A hole seared right through the left seat. What is a man to do, but cover it up with a red heart-shaped cloth patch that read, “I Love You,” a gift from a miffed college sweetheart?

And he had cooked with such single-minded devotion to his morning’s ruse that he forgot all about the electricity, which had returned like a sulking, lovelorn son, slinking out of the house one moment without permission, and thieving back in just as quietly, as if to evade a mother’s wrath. When Dhruva Ram returned to his trousers, they were busily smoking – “Phoos, phoos, phoos!” A hole seared right through the left seat. What is a man to do, but cover it up with a red heart-shaped cloth patch that read, “I Love You,” a gift from a miffed college sweetheart?

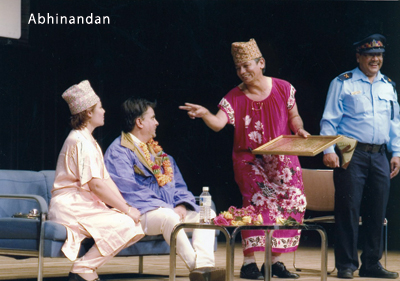

Over their long career as a comedy duo, Madan Krishna Shrestha and Haribansa Acharya have given a larger number of distinct personas to the field of Nepali comedy than any other group of performers. Dhruva Ram is just one of their numerous characters, and although played by Haribansha in their landmark television series Lalpurja, it is a creation of the duo, of two minds so united in their worldview and artistry that they speak as one. During interviews they often slip into the first person plural. “We think,” or, “We feel,” or, “We are.” On screen and stage they always play against each other: stingy father and moronic son, clueless landowner and cunning tenant, smuggler and customs officer, politician and guard to the realm of the dead. Off-screen, in more intimate moments, they address the world as one voice. It is tempting to search for a chink in the facade, a breach through which discord might flood out. But, even if it exists, it is not there for the public to see.

Over their long career as a comedy duo, Madan Krishna Shrestha and Haribansa Acharya have given a larger number of distinct personas to the field of Nepali comedy than any other group of performers. Dhruva Ram is just one of their numerous characters, and although played by Haribansha in their landmark television series Lalpurja, it is a creation of the duo, of two minds so united in their worldview and artistry that they speak as one. During interviews they often slip into the first person plural. “We think,” or, “We feel,” or, “We are.” On screen and stage they always play against each other: stingy father and moronic son, clueless landowner and cunning tenant, smuggler and customs officer, politician and guard to the realm of the dead. Off-screen, in more intimate moments, they address the world as one voice. It is tempting to search for a chink in the facade, a breach through which discord might flood out. But, even if it exists, it is not there for the public to see.

The public instead sees two faces to one civic conscience, two bodies to one artistic idea. The civic conscience behind the art is as serious and thoroughly considered as the comedy acts and personae are an outlandish bouquet of buffoonery. Look around town these days and you’ll see them on advertisements of all descriptions, promoting anything from a direct-to-home satellite television package to international money transfers. Rarely do they appear as the public figures Madan Krishna and Haribansha; more frequently, the figures on the hoarding boards depict their various avatars from their long career. After the 2008 CA elections, a survey by the Election Commission showed that a lot of voters had learned about the difference between proportional and direct elections from watching their shows Ama and Madan Bahadur – Hari Bahadur. False moustache and a mole the size of a two-rupee coin, for instance, for Madan Bahadur and Hari Bahadur’s advertisement for Western Union: the latter stealing cash from the former’s pocket, both grinning at the camera. Or, a head of silver hair for the octogenarian matriarch, Ama, who intuitively understands the importance of voting, even at her ripe old age. The Western Union ad tells the people that Western Union can be trusted. But the trust really comes from the esteem the Nepali people invest in the MaHa duo.

The public instead sees two faces to one civic conscience, two bodies to one artistic idea. The civic conscience behind the art is as serious and thoroughly considered as the comedy acts and personae are an outlandish bouquet of buffoonery. Look around town these days and you’ll see them on advertisements of all descriptions, promoting anything from a direct-to-home satellite television package to international money transfers. Rarely do they appear as the public figures Madan Krishna and Haribansha; more frequently, the figures on the hoarding boards depict their various avatars from their long career. After the 2008 CA elections, a survey by the Election Commission showed that a lot of voters had learned about the difference between proportional and direct elections from watching their shows Ama and Madan Bahadur – Hari Bahadur. False moustache and a mole the size of a two-rupee coin, for instance, for Madan Bahadur and Hari Bahadur’s advertisement for Western Union: the latter stealing cash from the former’s pocket, both grinning at the camera. Or, a head of silver hair for the octogenarian matriarch, Ama, who intuitively understands the importance of voting, even at her ripe old age. The Western Union ad tells the people that Western Union can be trusted. But the trust really comes from the esteem the Nepali people invest in the MaHa duo.

It has been a long journey for these two men past their physical – and perhaps artistic – prime, from the days of stage performances against the establishment, to public service television acts. Satire is their primary preoccupation, and humor the sauce with which they spice the nourishment of social messages. This has been their method since, in the early eighties, audio cassettes entered middleclass life in the urban centers of Nepal. Recordings of live performances of Yamalok sold so well that the MaHa duo could build houses and start families, rescuing them from the realities of desperation and depravity they so often deal with in their work. But, there was always risk involved in opposing a monolithic system like the Panchayat. “It was the age of audio. Any well off family had a cassette player. People were so scared to listen to the Yamlok skit that they locked the doors and windows and posted a sentry outside to make sure nobody caught them in the act of listening to a MaHa cassette,” they say. Why can’t you meet Kanun, Nyaya or Bikas in the streets of Kathmandu or villages of Nepal? Because, according to the skit, Law, Justice and Development have died and gone off to Yamalok – the Lord of Dharma’s realm where tally is kept of your karma and judgment passed, rewards or punishment dispensed.

It has been a long journey for these two men past their physical – and perhaps artistic – prime, from the days of stage performances against the establishment, to public service television acts. Satire is their primary preoccupation, and humor the sauce with which they spice the nourishment of social messages. This has been their method since, in the early eighties, audio cassettes entered middleclass life in the urban centers of Nepal. Recordings of live performances of Yamalok sold so well that the MaHa duo could build houses and start families, rescuing them from the realities of desperation and depravity they so often deal with in their work. But, there was always risk involved in opposing a monolithic system like the Panchayat. “It was the age of audio. Any well off family had a cassette player. People were so scared to listen to the Yamlok skit that they locked the doors and windows and posted a sentry outside to make sure nobody caught them in the act of listening to a MaHa cassette,” they say. Why can’t you meet Kanun, Nyaya or Bikas in the streets of Kathmandu or villages of Nepal? Because, according to the skit, Law, Justice and Development have died and gone off to Yamalok – the Lord of Dharma’s realm where tally is kept of your karma and judgment passed, rewards or punishment dispensed.

How did these two men get to this point where they are a political consciousness representing a moderate, middle-path vision of compromise between extremes? True performers to the end, they have always perfectly timed their injection into any outrage: in 1990, they wore gags and blindfolded themselves, and performed for the first People’s Movement. Soon after, the Panchayat regime was overthrown. In 2006, they came to the front not only as vocal dissenters, but also as the most trustworthy names to start a fund for injured demonstrators. Individuals from around the world contributed to the fund, without the bitter cynicism and accusations often reserved for public figures who step beyond the call of their vocation.

How did these two men get to this point where they are a political consciousness representing a moderate, middle-path vision of compromise between extremes? True performers to the end, they have always perfectly timed their injection into any outrage: in 1990, they wore gags and blindfolded themselves, and performed for the first People’s Movement. Soon after, the Panchayat regime was overthrown. In 2006, they came to the front not only as vocal dissenters, but also as the most trustworthy names to start a fund for injured demonstrators. Individuals from around the world contributed to the fund, without the bitter cynicism and accusations often reserved for public figures who step beyond the call of their vocation.

In May of 2010, the Maha duo was the main attraction at the Basantapur Durbar Square dabali, from where they addressed the Peace Rally: a crowd of people that had become fed up with the indefinite siege under which the UNCP-Maoists wanted to place them. In unequivocal terms, Madan Krishna outlined what he thought were the rights that all Nepalis had fought for. His technique consisted of rhetorical questions to which the throng – hundreds of thousands strong, packed into and radiating away from the Durbar Square – intuitively knew the answer which they shouted in unison. He asked those who agreed with him to raise their hands, and hundreds of thousands of fists and palms shot up in the air. The black-dotted swarm of heads and faces and eyes veiled behind raised arms and hard fists or open palms: if you had been there, witnessing both the moment and its significance, you would have felt a chill bolting down your spine; your pulse would have quickened. And you would have known that you had witnessed something so momentous that years later, recounting that moment for others, you could with confidence say that Madan Krishna’s rhetorical questions that morning changed the shape of Nepali politics. The siege on the city was lifted the very next day.

In May of 2010, the Maha duo was the main attraction at the Basantapur Durbar Square dabali, from where they addressed the Peace Rally: a crowd of people that had become fed up with the indefinite siege under which the UNCP-Maoists wanted to place them. In unequivocal terms, Madan Krishna outlined what he thought were the rights that all Nepalis had fought for. His technique consisted of rhetorical questions to which the throng – hundreds of thousands strong, packed into and radiating away from the Durbar Square – intuitively knew the answer which they shouted in unison. He asked those who agreed with him to raise their hands, and hundreds of thousands of fists and palms shot up in the air. The black-dotted swarm of heads and faces and eyes veiled behind raised arms and hard fists or open palms: if you had been there, witnessing both the moment and its significance, you would have felt a chill bolting down your spine; your pulse would have quickened. And you would have known that you had witnessed something so momentous that years later, recounting that moment for others, you could with confidence say that Madan Krishna’s rhetorical questions that morning changed the shape of Nepali politics. The siege on the city was lifted the very next day.

After that rousing, honest speech, they shed their public personae and became Madan Bahadur and Hari Bahadur – two men for whom, ostensibly, ethnicity or caste have stopped having meaning, so that they are both called Bahadurs: the everymen of the hills. They attempted to make the tense crowd laugh. It was a strangely deflating moment, especially after their personal speeches which were light-hearted and thoughtful, provocative and prescriptive, emphasizing the basic humanity of those whom we put at inconvenience through our individual or political aspirations. Was there any need for levity that morning? The crowd knew that after a few minutes it would have to confront the batons and bricks of Maoist cadres trucked in from around the country to “bring Kathmandu to its knees,” to strike with overwhelming terror at the heart of the sukila-mukila, a clean-collared class that lumped together the urban blue and white collar classes because even the blue-collar workers in the city had become complacent. What help would come from laughing a little before going out to have your head busted?

After that rousing, honest speech, they shed their public personae and became Madan Bahadur and Hari Bahadur – two men for whom, ostensibly, ethnicity or caste have stopped having meaning, so that they are both called Bahadurs: the everymen of the hills. They attempted to make the tense crowd laugh. It was a strangely deflating moment, especially after their personal speeches which were light-hearted and thoughtful, provocative and prescriptive, emphasizing the basic humanity of those whom we put at inconvenience through our individual or political aspirations. Was there any need for levity that morning? The crowd knew that after a few minutes it would have to confront the batons and bricks of Maoist cadres trucked in from around the country to “bring Kathmandu to its knees,” to strike with overwhelming terror at the heart of the sukila-mukila, a clean-collared class that lumped together the urban blue and white collar classes because even the blue-collar workers in the city had become complacent. What help would come from laughing a little before going out to have your head busted?

“We never do anything without humor in it. It just wouldn’t work,” Haribansha says in answer. Humor is the MaHa duo’s basic trade. Be it running and diving into the dirt after a rooster in faster-than-life motion, or a father-in-law tickling an India-returned migrant worker (and, in the process, finding a strange spot that reveals a deadly affliction after a proper health check-up), or wearing a neck-guard to bed. “Whatever the subject – be it political, medical or environmental – humor shall be given the first priority,” Haribansha eagerly reiterates his point. But, why? Is humor really that important while delivering a message, say, about tolerance between ethnic groups? To articulate their larger point that people shouldn’t put too much emphasis on the divisive issue of ethnic identity when there is an absence of good governance, MaHa would have to create flat, exaggerated caricatures of different ethnic groups. How does that help? A contesting point could be made that their insistence upon aspirations towards a homogenized identity, as typified in their Bahadur avatars, is just as politically hazardous, because it discounts genuine grievances of many political constituencies. And it smacks somewhat of a constructed unity, which is always a lie – just as much as it was during the Panchayat regime – that we are all one, and that inherited differences don’t matter.

“We never do anything without humor in it. It just wouldn’t work,” Haribansha says in answer. Humor is the MaHa duo’s basic trade. Be it running and diving into the dirt after a rooster in faster-than-life motion, or a father-in-law tickling an India-returned migrant worker (and, in the process, finding a strange spot that reveals a deadly affliction after a proper health check-up), or wearing a neck-guard to bed. “Whatever the subject – be it political, medical or environmental – humor shall be given the first priority,” Haribansha eagerly reiterates his point. But, why? Is humor really that important while delivering a message, say, about tolerance between ethnic groups? To articulate their larger point that people shouldn’t put too much emphasis on the divisive issue of ethnic identity when there is an absence of good governance, MaHa would have to create flat, exaggerated caricatures of different ethnic groups. How does that help? A contesting point could be made that their insistence upon aspirations towards a homogenized identity, as typified in their Bahadur avatars, is just as politically hazardous, because it discounts genuine grievances of many political constituencies. And it smacks somewhat of a constructed unity, which is always a lie – just as much as it was during the Panchayat regime – that we are all one, and that inherited differences don’t matter.

I am wrong. Haribansha explains why – “More than humor, pathos leads good comedic characters. If a character makes people laugh while he is crying, that is a stronger humor. That has more depth, more dimension.” That May morning in Basantapur, the crowd was laughing at Haribansha’s very personal frustrations about not being able to live the simplest life given to a citizen. In his humor was the reflection of the pains of a citizenry forced to fight fellow citizens with a differing political view. This inflated his character from a flat caricature – the stock of most comedy – into a rounded figure of tragedy. What appears as comic is actually tragic at its core. Dhruva Ram Pandit, the loser-hero of Lalpurja, is easy to laugh at because he is tragic to his core. A top-down intervention in his story – an earthquake that flattens his ancestral home – leads him down a pathetic road of annihilation: home lost, land wrested away by a conniving tenant and his chorus of real-estate agents, drugged, robbed, jailed, thrown out of the cowshed that was his last and finally set to wander with his elderly mother, tainting with pain the into-the-sunset final shot usually reserved for heroic westerns or tales of requited romance. All along, he makes us laugh at him, because we recognize how his character has halved the distance between his story and ours.

If pathos inflates humor into the dimension of the tragic, what does rage do? Righteous rage is another fuel to MaHa’s comedy. In 50/50, one of MaHa’s earliest works for the television, a customs officer who first seems upright and honest turns into a corrupt colluder to a gold smuggler who drops a brick – of gold – every time he is made to squat. MaHa’s political outlook has been consistently forthright, riddled with middleclass morality, a landscape where Right and Wrong clearly delineate themselves, and thus create the space righteous rage occupies in the civic consciousness. This outlook was most recognizable to the Nepali middleclass, which was just discovering television in the mid-eighties when MaHa made the leap from audio cassettes and stage performances to television specials. The middleclass recognized its rage reflected in 50/50’s satire. But, the notion that the clean-collared bureaucracy was a dirty bunch of the corrupt and the greedy was not as easily digestible to the upper-crust of the society in the Panchayat era. Before airing 50/50, the censor at Nepal Television refused to pass the program unless an alternative ending was provided, where, miraculously, the entire story turns out to be a dream.

Two dreams, actually – that of the gold smuggler, and that of the petty bureaucrat, a collusion of aspirations for the upwardly mobile middleclass. The story of Nepal between 1990 and 2002 is born precisely from this nexus. This prophetic strain in MaHa’s work seems to be the punishment that goes on to seek its offense: the more vehemently they make a comment on an unfortunate social reality, the stronger it seems to manifest itself. Back to Lalpurja – our hapless land-owning hero is forced to sleep with a neck-guard around his throat, because he rightly worries that he will be finished off in the night by his tenant if he forgoes caution. Soon after Lalpurja aired, a new land reform law was presented, failed, and the People’s War started. Land and its ownership is the issue here: who should have the right over farming land? The absentee landowner, or, the family that tills it and tends to it? Today, with Dr. Bhattarai leading the government, the answer seems obvious: the farmer who works the land, of course.

But, watch Lalpurja, and that notion of justice and injustice is absolutely upturned. An individual can – and often does – stand in defiance of his class definitions. For some, their footing proves too slippery to let them keep their standing within the limits of their politically defined class. Dhruva Ram’s land is valued at six million rupees, only a quarter of which he is legally obligated to give to his tenant-farmer Ghanshyam. But Ghanshyam, the mohi tenant-farmer, concocts a convoluted rococo of comedy that ensures total destitution and homelessness for the talsing landowner Dhruva Ram. Look around today, and you’ll find iterations of the same story echoing from hill to hill where muscled proletariats have expelled even poorer “class enemies” from their land and property because of caste or ethnic difference, or for generational vendetta. Nearly all real-estate Mafioso who kill and threaten their neighbors to develop colossal gated communities are card-carrying revolutionaries, while landless squatters are evicted from their tent-slums to build parks dedicated to dead communist leaders. The most famous revolutionary these days is not a leader, but a Dr. Bhattarai’s lackey, a convicted murderer who killed not for political reasons, but out of pure caste hatred. MaHa’s offense was to dream up Dhruva Ram, a misfit and discredit to his land-owning, upper-caste stereotype. Their punishment is the perversion seen in politics today.

Over 32 years of partnership, Madan Krishna and Haribansha have made people laugh while actually teaching them: about tuberculosis in Chiranjivi, in which a greedy son in law waits for a tubercular elder to die. But, timely cure saves the elder, keeping him alive longer than the greedy son in law. Raat, in which a jovial guard on holiday from India turns out to have contracted HIV/AIDS after raping a Nepali sex-worker who sought shelter with him. Bhakunde Bhoot, in which a polythene bag full of garbage thrown in the streets keeps returning to the house until it is properly disposed of in a garbage container. Pandhra Gatey, in which a son insists upon getting married a day before his college girlfriend’s wedding, and in the process takes the family on a cross-country, pan-ethnic journey and a fight against the dowry system. Dashain, a meticulous record of the pitfalls of greed and ostentation during the festival as celebrated among the urban lower-middleclass. To their lasting credit, MaHa have even given Nepali culture the greatest moments of horror and suspense on screen: Haribansha’s rendition of a coming-of age ditty, “Ghaas katney khurkera, aayo joban hureka... Kaslai diun yo joban?” is still unsurpassed in its capacity to deliver terror into the hearts of a viewer. I used to waylay a friend in boarding school, hoarsely, slowly singing “Ghaas katney khurkera...” as he walked to the bathroom in the night. He’d scream and run to the cocoon of his quilt, to emerge only in the morning to punch me in the gut.

Comedy on Nepali television stations, sadly, is far removed from the biting wit and satire, humor and pathos that MaHa insist upon. All is canned laughter and tyauun... of raised eyebrows, twitching noses and flailing hands. Every joke is a talking point on the topic du jour, lifted from newspaper headlines and repeated infinitely. A trend that perhaps started with Twakka –Tukka, a collection of short, not-very-funny jokes – has now degraded to episode long jokes with no punch line, no insight that the viewer hasn’t already considered or confronted. Will real comedy – with satire and pathos – ever return? MaHa aren’t holding their breath. They don’t see how it is possible for good comedy to come out of the political chaos that reigns in the nation. Nepal is a humorless nation right now. No group has the honesty to laugh at itself, and the laughter that comes at the expense of another group is crude, full of cruelty.

The decades old partnership is visible in their relationship in private. Madan Krishna, the levelheaded foil to Haribansha’s persistent buffoon, hovers around impatiently, watching the interviewer more often than participating in the conversation. A year back, during another conversation, Madan Krishna had insisted upon balance between Ma and Ha when it came to representation in a possible comic-book. Haribansha speaks almost entirely in the first person plural. Haribansha leans forward to talk about leaving his old home at Comfort Housing in Budhanilkantha, but Madan Krishna putters around asking if he should change into something more presentable for the photographer. Haribansha shows the script for an upcoming stage show – pages filled with a scrawl so personal as to be illegible even to him – while Madan Krishna tries to email the duo’s biography to the photographer. Haribansha finds time for small talk while Madan Krishna reminds him of the lunch waiting upstairs. I have a moment to myself in Madan Krishna’s living room. I search the wall-to-wall shelves on one side, full of trophies and mementos, for a sign of their partnership. I can’t find a single photo of Haribansha on the walls, neither a single trophy on the shelves made out to Madan Krishna alone. I wonder – What is Haribansha’s trophy shelf like?

The kitchen is on the fourth floor. MaHa say their goodbyes and prepare to go upstairs. At the bottom of the stairs are warm slippers for the kitchen. Haribansha slips his feet into a pair, seems puzzled, switches them around. Madan Krishna turns around to watch. Haribansha grins like a child who has stumbled upon a mystery: no matter how often he switches the slippers from one foot to the other, they look odd, always on the wrong foot. He switches around the slippers once more. “If I wear it like this, it looks like they are both on wrong feet, like a child would wear them. So I switch them around, and they still look wrong. There is no right way of wearing them,” he laughs. Madan Krishna, a few steps above him, smiles and nods, waits. “Then, there is no wrong way of wearing them,” Haribansha switches slippers again. Finally, I recognize this person – a man so straightforward in how he sees the world that he delights in simply recounting his most mundane actions, and somehow infuses them with meaning, like a character from a fable whose every action translates into a moral. Like Dhruva Ram who, after he finished “being employed for the day,” went home, washed his only pair of work clothes and set them out to dry overnight. He cooked, ate, cleaned up, woke up the next morning, cooked, ate, cleaned up. And, prepared to go to work.