Unlike the Western calendar, the Nepali New Year (and a host of other New Years all over Asia, from Thailand to Tamil Nadu to Bangladesh) starts on April 14 this year. Why, you may ask. The reason is astrological. The Sun has completed its path around the twelve signs of the zodiac, and on April 14, enters Aries, the first sign, to start the cycle anew.

Aries is ruled by the ram, an animal characterized by quick movement and big leaps. Gamboling along, the first sign shows the initiative and drive of new beginnings, the energy to start afresh, and the power of regeneration.

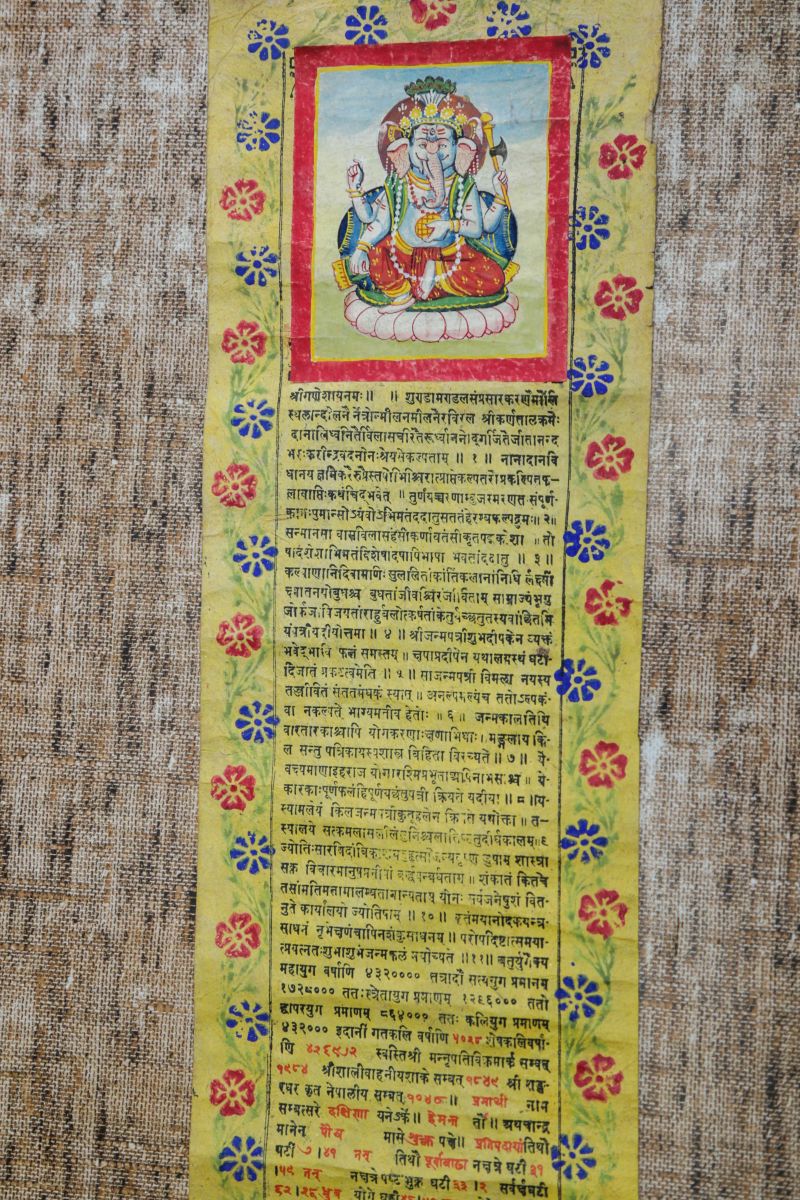

Astrology draws mockery from most people. A jyotish, or astrologer of the East, is casually called “bajay,” or grandfather, with a slight element of condescension. Western astrologers are often thought of as weak-minded women with too many scented candles.

Part of the jyotish’s shabby reputation comes from this conflation: at some point, Western astrologers and Eastern jyotish became conflated as one and the same tradition, although they are vastly different in history and nature.

To point out the most basic difference: Western astrologers and Eastern jyotish do not share the same zodiac. Despite using the same names for signs, the zodiac is at least 23 degrees apart. This means the Aries of jyotish and the Aries of Western astrology are pointing to two entirely different sections of the sky.

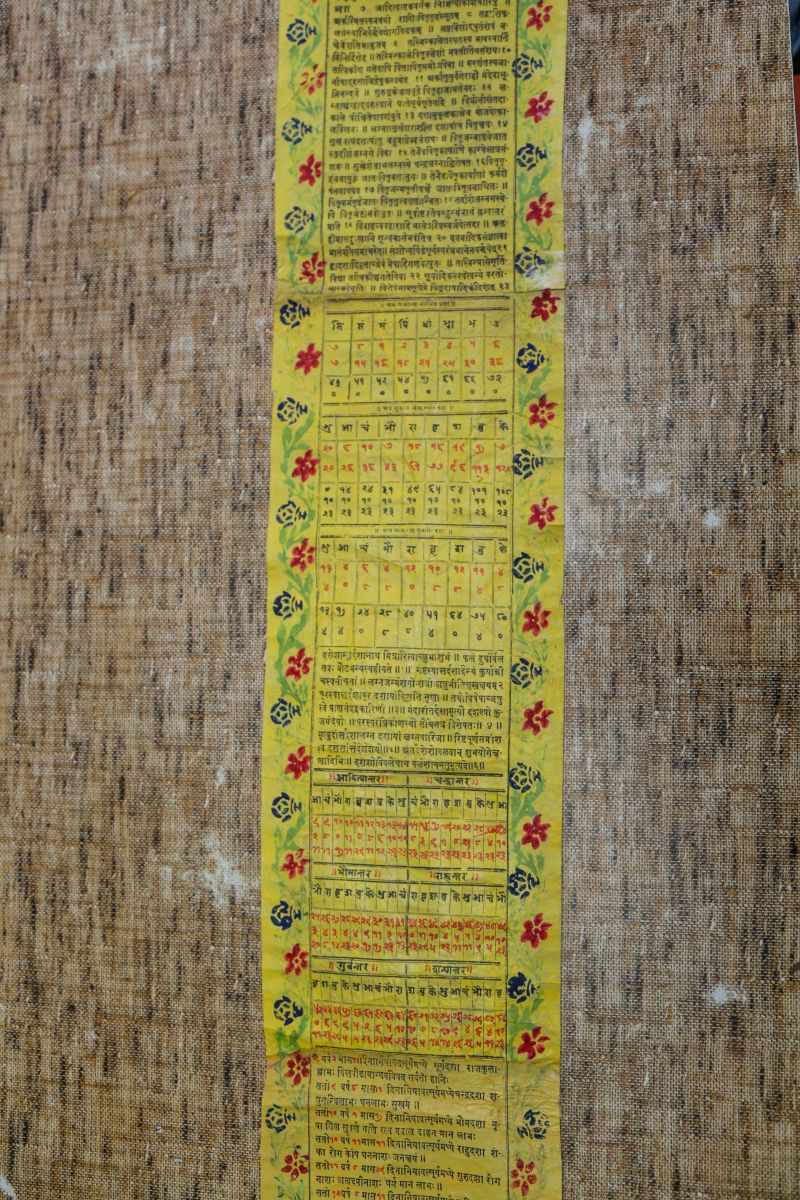

To take an example: Western astrologers say that Saturn is currently transiting in Capricorn, whereas the jyotish say it is in Sagittarius, one sign behind. All of us will assume, due the presumed supremacy of Western science, that the Western one must be correct. But in fact if you consult scientific astronomical sites, you will see that Saturn is close to the real constellation of Sagittarius. In other words, jyotish are following real constellations and real movement of planets, whereas Western astrologers are following an imaginary zodiac in the sky, which doesn’t correspond to the movement of heavenly bodies into observable constellations.

I will spare you the elaborate reasonings put forth by Western practitioners of astrology on why they are correct about their zodiac, but it has something to do with the “procession of the equinoxes.” Anyways, it is wholly wrong. Saturn is not anywhere near Capricorn at present. But, most followers of astrology don’t care about these nuances. You can see millions of followers watching popular Western astrologers give forth their psychological readings about love and matchmaking on Youtube, whereas the jyotish doing astronomically correct readings get a few thousand views, at most.

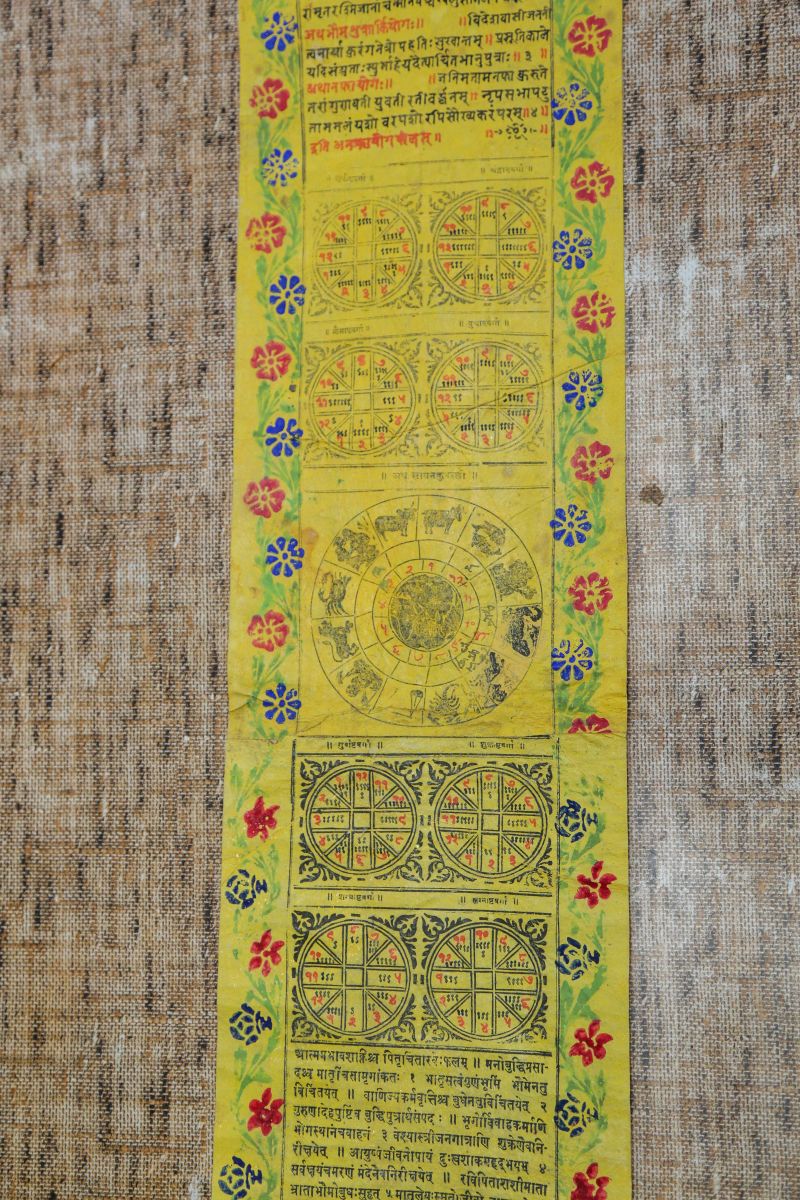

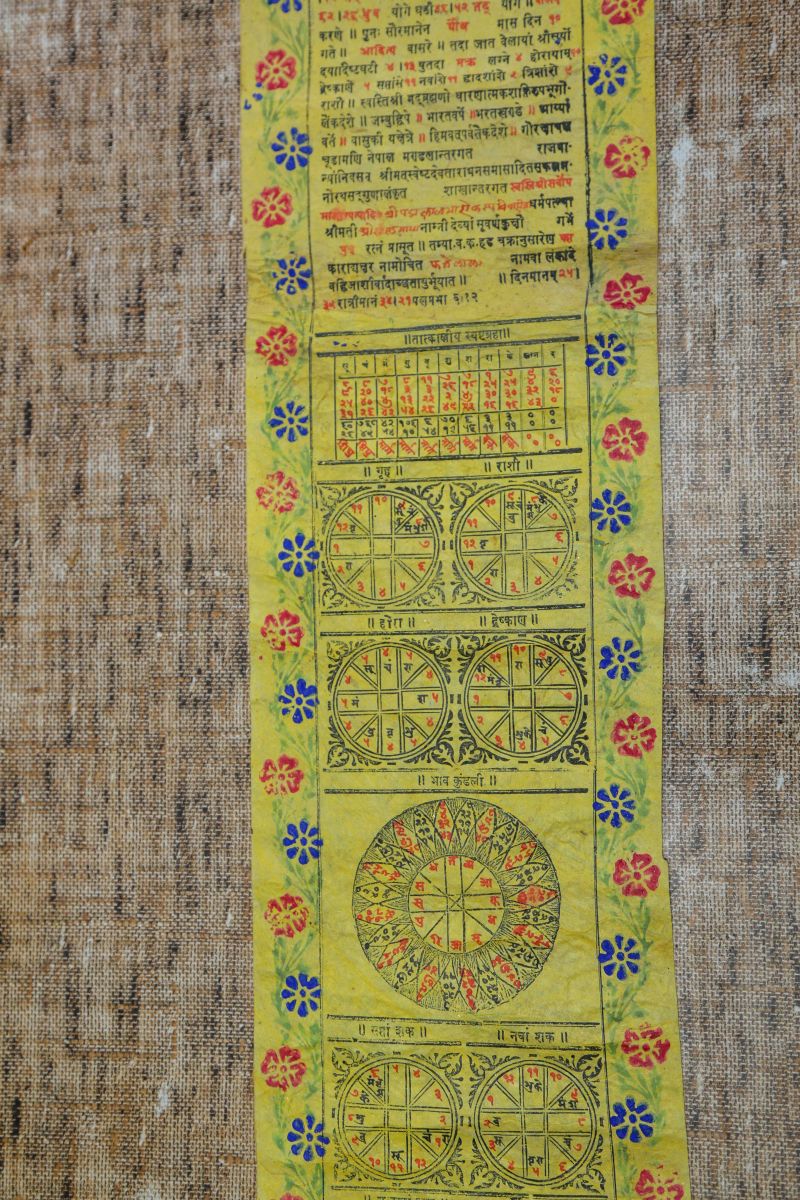

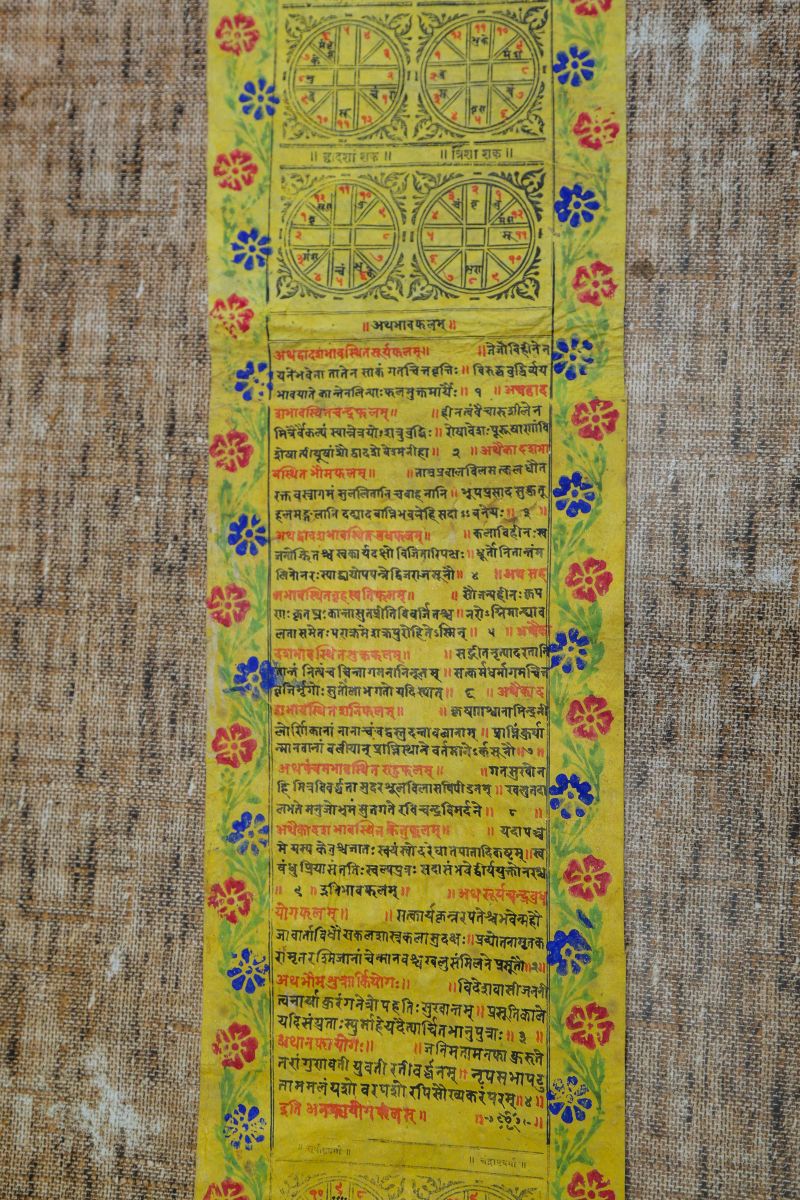

Jyotish, the Eastern tradition of computing the movement of stars and planets, is called “sidereal” in Western parlance. “Sidereal” means “of the stars.” Jyotish practitioners have always followed the movement of planets into constellations on a daily basis, because the movement of the moon, sun, and planets remain central to Hindu cosmology and rules its every second, minute, and hour. All of this is somehow obscured and overlooked, and all astronomical findings have passed gracefully as a legacy of sharply observational Western minds. We assume astronomy sprung, like Athena out of the head of Zeus, from the fountainhead of rational Western science. But there is plenty of evidence to suggest that ancient Hindus were observing outer space with great acuity and precision long before Westerners. The Surya Sidddhanta is one such treatise which documents astronomical studies in ancient India.

The recent furor created by the visualization of the black hole by MIT scientists made me realize how much observations of astronomical phenomena by Eastern traditions have been obscured by the allusive language and imagery of Sanskrit and jyotish. The jyotish knew the galactic center, the center of the Milky Way, where the black hole is located, as “Mula Nakshaktra.” “Mula” means the root, and it signifies origins, roots, and the source of all life. Some have suggested this nakshaktra corresponds to the imagery of the navel of Vishnu, out of which all life came forth.

Mula is ruled by Nirrti, the fierce goddess of dissolution and destruction. It is easy to imagine Nirrti as a proto-Kali. Kali is pictured garlanded with skulls, holding a skull, with her tongue hanging out. Her feet are planted on Shiva, the cosmic force of destruction. Kali is Time personified. She brings forth life, and then swallows back into her vast black underbelly every form of life that was ever created, through the cyclical process of birth, death and regeneration.

Jyotish give precise calculations for the nakshaktras (constellations), of which there are 27. Ashwini, the first nakshaktra, is where Sun begins its annual journey. The Ashwin Kumars were the horses that drove the Sun on his chariot to journey around the earth everyday, in Hindu mythology. Like the horses, people born under Ashwini nakshaktra are swift, fast and efficient decision makers who are always on the mark. They are also thought to be great healers.

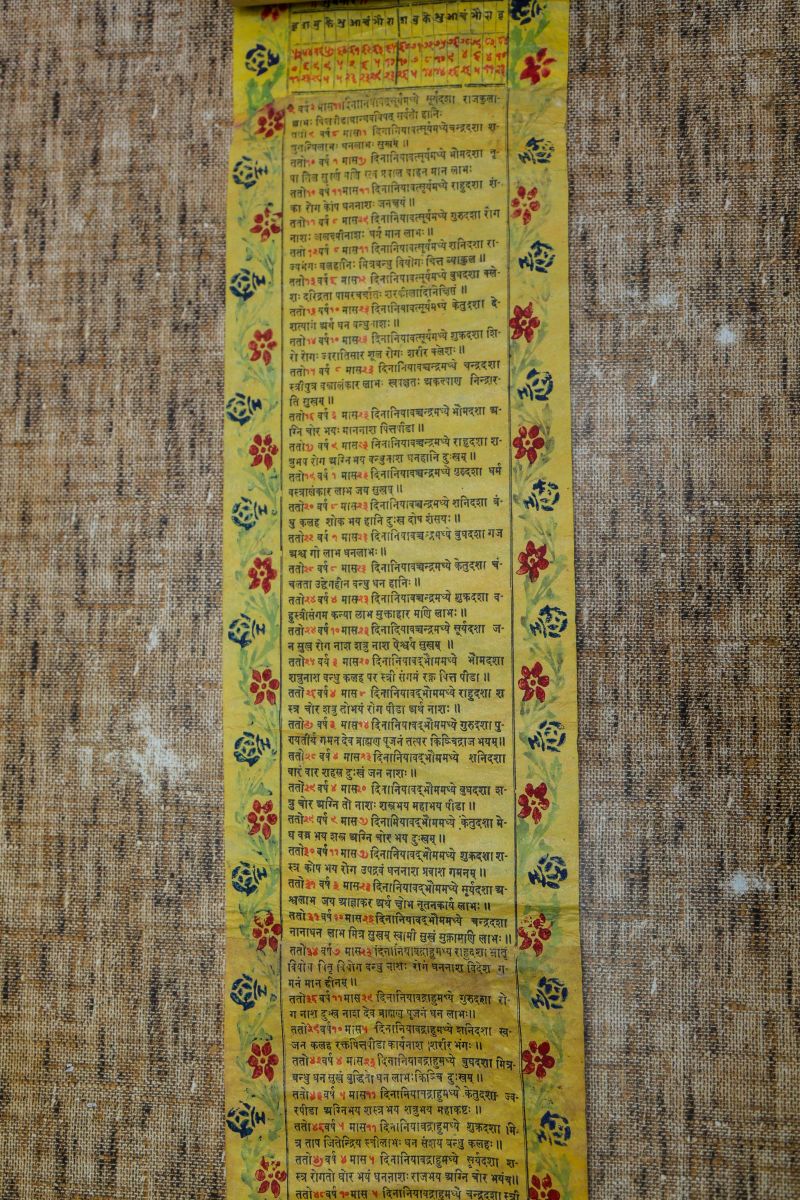

Ashwini is ruled by Ketu. Ketu is one of the navagraha of Hindu cosmology, and the first graha in the sequence of the dashachronology. Grahais a spiritual force that seizes when the time is right. Western translators have reduced Rahu and Ketu to “the north and the south nodes of the moon.” I personally feel this is an entirely inadequate material description of what are essentially powerful spiritual forces. The Sanskrit term graha encompasses a host of attributes missing from mere “planet,” which is seen to be more of an aggregation of rocks and gases floating at a certain axis and velocity.

Just because jyotish has these powerful poetic and philosophical concepts mixed in with precise mathematical calculations of astronomical phenomena doesn’t disqualify its scientific contribution. But in fact this is what modern science has done: it has seen the entire jyotish corpus as devoid of any scientific merit. I find this disheartening not only because this approach encourages ostensibly scientific young people of the subcontinent to reject their philosophical and scientific heritage, but also because it appropriates what may have been the first studies of mathematics and astronomy as “Western” inventions.

Hindus continue to watch and calculate the movement of the planets everyday because for us this is not just a passing amusement and scientific curiosity, but the very basis of our spiritual life. Where the planets go dictate our fasts, our devotional pujas, our shraddhas to the dead. Every material move, whether to buy land and house, or move to a new location, is dictated by the good or bad timing of planetary movement.

It is time to recognize the centrality of how Hindus have always seen the heavenly bodies as part and parcel of our own material existence on earth, and how we have never felt separate from our billion-year old origins. It is time to recognize that this spiritual practice may have been the origins of not just present day astronomy, but many elements of modern mathematics, including the now indispensable zero, which sprung out of these daily complex calculations.