For Christ and spices! was reportedly the battle cry of the Portuguese crew under Vasco

For Christ and spices! was reportedly the battle cry of the Portuguese crew under Vasco

de Gama as they landed in Calicut on a sultry dawn on 21st May 1498. Calicut was then, as it is now, the gateway to the world’s greatest pepper growing region. The supreme quality of pepper crops of the south Indian State of Kerala was attributed partly to its unusual twin monsoons.

In fact, the peppercorns of Iddicki, high up in the mountains of Kerala, are always ‘dark and heavy and bursting with flavor’. The discovery of pepper, and subsequently, other spices, by the Europeans, led to great trade rivalry between the leading powers of the times, chiefly, Portugal and Spain. For much of the 15th and 16th centuries , these two countries engaged in a continual war to gain control of the world’s spice trade.

It can also be said that the battle for the world wide control of the spice market led to the formation of the world’s first business cartel, the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC) in 1602, an association of merchants meant to reduce competition, share risk and realize economics of scale. For, indeed, the spice trade encompassed great distances, involved much risk, and huge sums of monies were at stake. By 1670, VOC was the richest corporation in the world and was financing 50,000 employees, 30,000 soldiers and 200 ships.

The lure of spices resulted in a colonization spree around the globe and the first order of business of VOC was the conquest of the Banda archipelago, the world’s only source of nutmeg and mace. Similar conquests of many islands of the Indian Ocean, known generally as the ‘Spice Islands’ followed, and the spice trade swelled the coffers of many sultans of the east besides obviously, the exchequers of many European kings.

However, by the 1730’s, the spices that were once limited to tiny islands in the hidden archipelagos were being cultivated worldwide in large quantities. Monopolies, hereto the only means of spice trade, gave way to markets that still remain romantic due to the inter- cultural mix of western enterprise and eastern exoticism. That is why the spice bazaars of Kerala, Ambon, Rotterdam, London and New York still retain a fascinating charm. In Baltimore, Al Goetze of McCormick, the world’s largest spice firm, is referred to as a ‘modern day ‘Marco Polo’ by his admiring colleagues. As is Alfons van Gulick, the head of Rotterdam’s Man Producten, the world’s biggest and most influential spice-trading firm.

In Kathmandu, Bhai Ratna Bajracharya can be said to be Nepal’s ‘Marco Polo’ of the spice trade. He first started the spice business 30 years ago and his shop, ‘Shankha Pasal’ in Kothunani, Ason, is still a major dealer of condiments as well as dry fruits. Today his son, Sajeeb, looks after the business and the Nepali ‘Marco Polo’, aged 75 now, has retired. The name of the shop literally means ‘Conch Shop’ and is so named because it also deals with another business that is quite exclusive, that of conches. In fact, it is possible that their spice trade began after they had started the one in conches. It could be that the conches were imported from the shores of south India and since this region is famous for spices, the business of condiments followed as a natural adjunct.

Although today, they are mainly flavorings of food, a hundred other uses have been found throughout history for spices. In ancient Egypt cassia and cinnamon were thought to be essential for embalming, and anise marjoram and cumin were used to rinse off the innards of the worthy dead. However, from time immemorial, spices have been particularly valuable because they preserve and make the ‘less well preserved’, palatable; masking stench of decay and staleness.

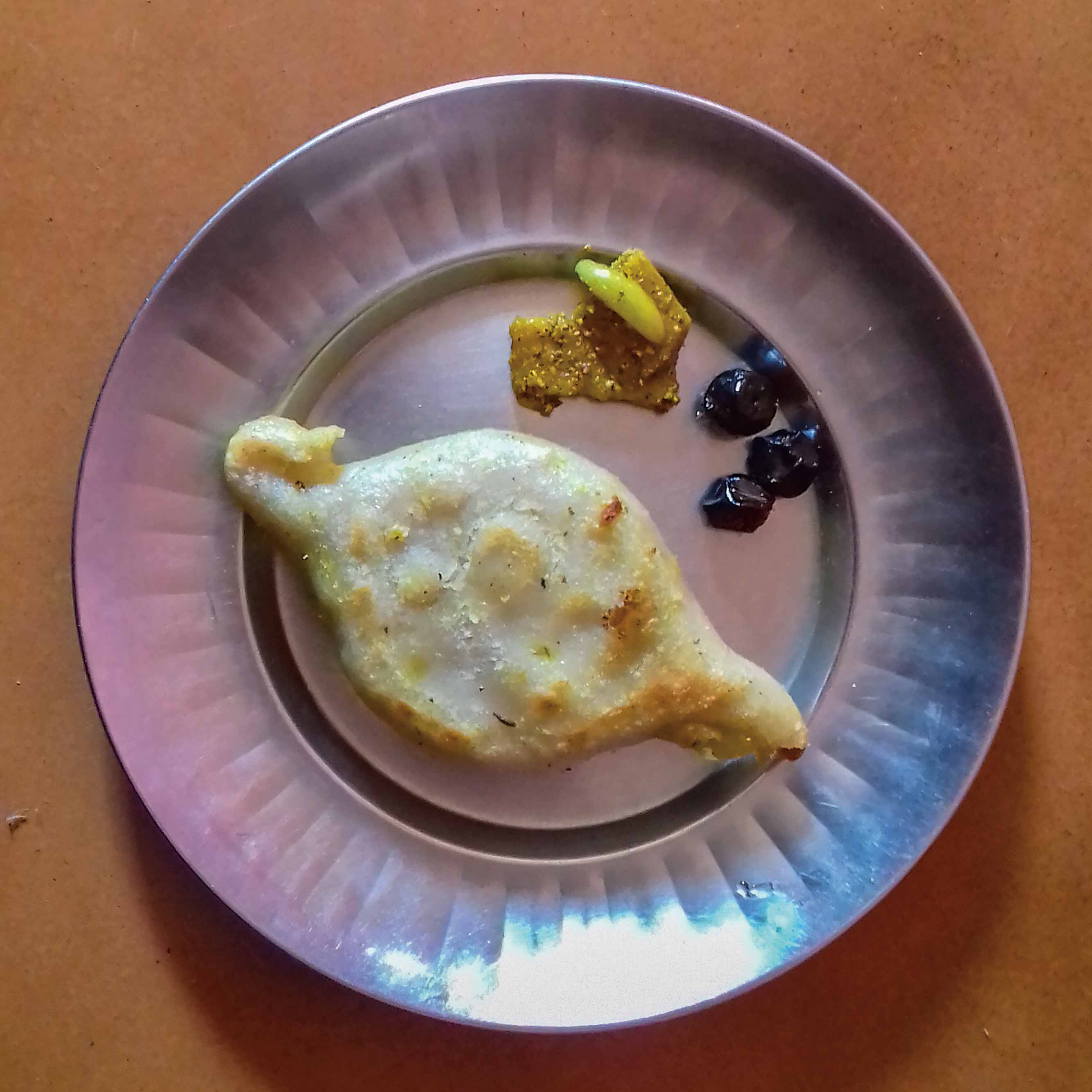

Of course, spices are treasured and indispensable mainly because, besides imparting dark husky aromas, they enhance the taste of food and do our palates a huge service. The popular ‘garam masala’, a mixture of a dozen spices is a perennial favorite with the masses and used to flavor many dishes, especially that of meat. As the name implies, it imparts heat (‘garam’ means warm or hot) and is therefore particularly beneficial in the cold months. ‘Garam Masala’ contains equal quantities of jeera (cumin seeds), dhania (coriander), marich (black pepper), methi (fenugreek), besaar (turmeric), sukmel (cardamom), elaichi (black cardamom), dal chini (cinnamon), tez pata (bay leaf), luang (clove), jaifal (nutmeg), and saipatri (mace). Salt and red chilly are of course other spices that are added to taste.

Whole ‘Garam Masala’ costs about NRs.500 per kg while the grounded version will cost around NRs.600. Among its ingredients, mace is probably the most expensive costing from NRs. 800-NRs.1000 per kg, while nutmeg and clove cost about NRs.400-NRs.600 per kilogram. Price of cardamom is around NRs. 400, bay leaf is NRs.50, and fenugreek, NRs.40/kg. Coriander costs NRs. 70 and the rest are priced between NRs.100 to NRs. 200 per kilogram. Kesar (saffron), which imparts a tantalizing fragrance is one of the more exotic items among spices and herbs and can cost up to NRs.50,000 per kg.

According to Sajeeb, it is advisable to buy the whole spices individually and have them ground separately. The various mixtures available in the market do not always guarantee quality, as more of the economical spices could have been added and less of the more expensive ones. In addition, according to Sajeeb, “Indian spices are among the best and so, are more expensive, but cheaper spices are also imported from places like Singapore, and it is likely that these cheaper spices are being added in mixtures.”

Whole spices can be ground in a coffee grinder, food processor, pepper grinder or mortar and pestle. Cleaning the grinder after use is easy enough. All one needs to do is add some sugar or uncooked rice and process. One can also dry roast spices by toasting spices for 2-5 minutes or until spices are lightly browned, on a heated heavy skillet, stirring constantly to prevent burning. This can accentuate the aroma of spices like cumin, coriander, mustard seeds, fennel seeds, poppy seeds and sesame seeds.

Spices are meant to be used sparingly, so that rather than dominate with their flavor, they enhance and emphasize other flavors. If whole spices are to be added to cooking, it is advisable to tie them up in cheesecloth for easy removal. Whole spices should be added during cooking to permit their flavors to permeate the food. Ground spices or herbs should be added midway or towards the end so that their flavors do not dissipate. For raw food like salads, fruits and juices, it is better to add spices and herbs a few hours before serving to allow the blending of flavors.

Over time, spices lose color, taste and aroma, therefore they should be stored in airtight containers away from exposure to light and heat. Dampness can cause spices to cake and crumble. Red colored spices like chilli powder, cayenne pepper and paprika should be refrigerated to prevent loss of color and flavor. A fairly constant temperature of about 70 degrees Fahrenheit is ideal for most spices. Whole spices retain their taste and flavor longer than grounded ones and the shelf life of different spices varies. As a general rule, among whole spices, leaves and flowers’ shelf life is one year, seeds and barks, over 2 years and that of roots, also over 2 years. When ground, leaves and flowers last for 6 months, seeds and barks for 6 months also, and roots for a year.

In the Nepali language, spices are known as ‘masala’. So too are dry fruits. A mixture of both plays a very important role in the post delivery care of new mothers. A special mixture is made for nursing mothers. This is called ‘sutkeri masala’ and consists of gund (edible gum), dry fruits, batisa (mixture of 32 herbs), jwano (thyme), methi (fenugreek) and sounf (dill). It is considered a potent concoction, taken dissolved in milk or water, and is said to impart almost all the essential nutrients in concentrated amounts. Similarly, for infants, a customary feed supplement has always been a mixture of dates, almonds, cashew nuts, pistachio and nutmegs. The serving of supari (betel nuts), sukmel (cardamoms) and luang (cloves) are obligatory after any feast.

Dry fruits as such are also important parts of tradition and religion. The coconut is considered to be a ‘sagun’, i.e. an auspicious offering, and is offered to most deities during religious festivals. In social events like marriages and Bhai Tika during the Tihar festival, dry fruits are an essential component of the rituals. Among dry fruits, kaju (cashew nuts), kagaje badam (almonds) and pista (pistachio) are the most expensive, costing NRs.500 to NRs.700 per kg. Kismis (raisins) cost NRs.160-NRs.250, okhar (walnut), NRs.180, chahara (dry dates), NRs. 120 and nariyal (coconut), NRs. 180-NRs.200. Aaru (apricot) costs NRs.400/kg, anjir (fig), NRs. 450 and sultana (raisins with seeds), NRs.450.

Dry fruits are highly nutritious. Raisins are useful in cases of debility and wasting diseases and also helpful for relief of constipation as well as for regularizing bowel movement. Besides, raisins being a rich source of iron, enriches blood and cures anemia. Ayurveda advocates black raisins for re-establishing sexual vigor. Cashew nuts, aside from being a rich source of potassium, vitamin B, folate, magnesium, phosphorous, selenium and copper, is rich in mono unsaturated fat and so is useful in preventing heart diseases. Dates are said to be useful for relieving hangovers and constipation, and also for building up the heart.

Almond is one of the most prized among dry fruits. Like cashew nuts, almonds have plenty of vitamins and minerals, and help in the creation of blood cells and hemoglobin, aside from strengthening muscles, nerves, bones, heart and liver. Almonds are also said to help in the proper functioning of the brain, and almond paste is supposed to be very useful for softening skin and removing black heads, dry skin and pimples. Almond oil is said to prevent hair from thinning, prevent dandruff and the early graying of hair. Almonds also assist in preventing anemia and constipation, relieving bronchial diseases, hoarseness and cough, and help in cases of sexual dysfunction caused by a nervous breakdown.

With so many beneficial uses, is it any wonder then, that things that make our lives more interesting are referred to as the ‘spice of life’? ‘Masala’, whether spices or dry fruits, are indeed wonderful blessings bestowed upon mankind—blessings that add taste, flavor and zeal to the otherwise humdrum fabric of everyday living.

More than just your usual lapel pins

The lapel pin is a men’s accessory worn on the lapel of the jacket which serves as a...