As the biscuits were my choice I had no right to complain, but being now without any teeth to speak of I found them singularly unappetizing. The teeth had been carelessly dropped in the Trisuli river when bathing there the second morning out, and no doubt they were now entering the Bay of Bengal. Such a blow so early in the campaign, by making eating, smoking a pipe, and talking, a little awkward, struck at my morale. (Tilman, in Nepal Himalaya, 1952)

As the biscuits were my choice I had no right to complain, but being now without any teeth to speak of I found them singularly unappetizing. The teeth had been carelessly dropped in the Trisuli river when bathing there the second morning out, and no doubt they were now entering the Bay of Bengal. Such a blow so early in the campaign, by making eating, smoking a pipe, and talking, a little awkward, struck at my morale. (Tilman, in Nepal Himalaya, 1952)

Trekking tends to inspire stories, and of all the story-tellers who can resist Bill Tilman’s ironic humor? – whose tale of the lost dentures is one of many that usher in the modern age of trekking.

Beginning several centuries ago some travelers described episodes even more harrowing (than losing their teeth) on the Himalayan trails. In December 1721, for example, on their way between Lhasa and Kathmandu, the Italian Jesuit priest Fr Ippolito Desideri and a companion negotiated the difficult track down the Bhoté Kosi river gorge south of Kuti (now Nyalam, Tibet) to Kodari and on into the Valley of Nepal. It took them 14 days—

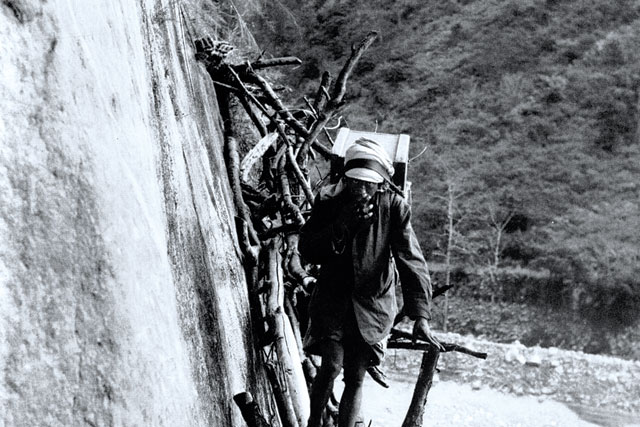

“The road skirted frightful precipices, and we climbed mountains by holes just large enough to put one’s toe into, cut out of the rock like a staircase. At one place a chasm was crossed by a long plank only the width of a man’s foot, while the wood bridges over large rivers flowing in the deep valleys swayed and oscillated most alarmingly. During the last days we ascended and descended one mountain after another, but they are not so bare as in Thibet, there is grass and the pleasant shade of trees. Here it is of course impossible to ride, but easy to find men who will carry you. “They have leather straps across the shoulders and forehead attached to a board about two hands in length and one in width. On this one sits with legs hanging down, and arms round the man’s neck. Father Felice, although old and tired, insisted on walking with me until at last I persuaded him to be carried, but he was so tall and heavy that it was difficult to find men who would carry him, so the poor Father suffered much.”(Desideri, An Account of Tibet, 1932)

Such vivid and fearful adventures were common. The old missionary journals like Fr. Desideri’s were filled with awe and fear, and their trials on the old trails were often described in painstaking detail. They were priests on missions. They faced the dangers out of necessity to reach their goal. For them it was not outdoor recreation, nor the sort of exploratory ‘fun’ that modern adventurers seek. Rather it was obstacles to be overcome and challenges to the faith. The stalwart missionaries crossed the Himalayas on rough tracks cut into cliffs, in unpredictable weather, without adequate food or shelter.

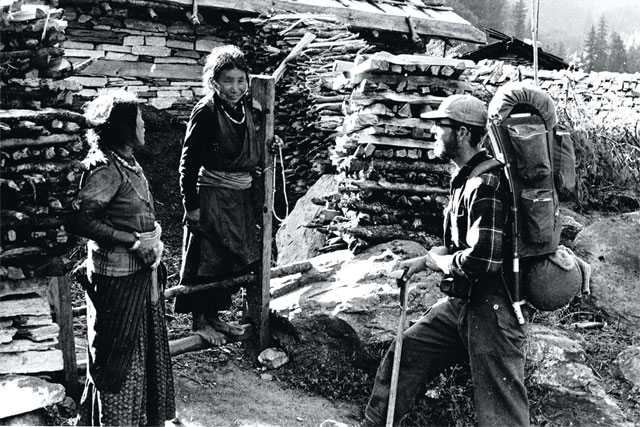

Today’s trekkers, by contrast, expect something quite different: comfortable nights in inns or guest houses, or in tented camps set up by Sherpas; motor roads to the trailhead; GPS to keep from getting lost; and access to weather forecasts on the Internet. We now outfit ourselves in the most advanced gear and expect to eat well from modern ‘teahouse trekker’ menus, food that would shock even the most clairvoyant and far-sighted missionary, including coffee lattes, apple pie, cinnamon rolls, banana pancakes, cheese omelets, and lasagna.

It was the early to mid-20th century before writings about serious mountaineering and trekking stories began to appear. To more modern mountaineers, trekking, whether easy or hard, was the objective, or for climbers it was a major part of getting to the destination, the base of the mountain. As a result, some of the best early trek writing is found in books like those of the stalwart mountain-travel writer, H.W. Tilman. His Seven Mountain-Travel Books (1983), including Nepal Himalaya (1952), gives us some of the very finest early trek-story reading.

Tilman on Mountain-and Trek-Travel

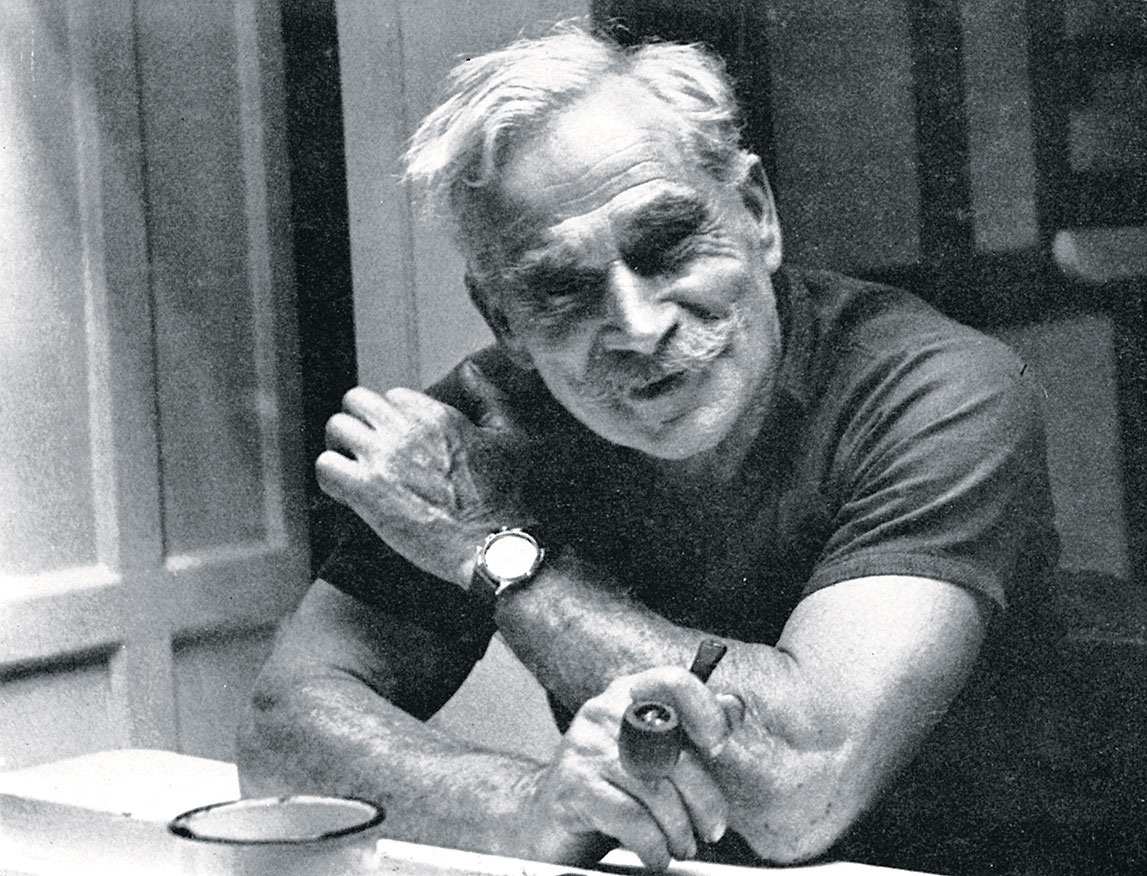

Harold William ‘Bill’ Tilman (b.1898) was educated in an English boy’s school, and fought as a youth in World War I, before setting off for Africa to become a coffee farmer and, ultimately, one of the best known British mountaineers of the last century. Another British coffee farmer and climber, Eric Shipton, introduced Tilman to climbing in Kenya and in the Ruwenzoris of Uganda. Shipton had already been to the Himalayas, to Mount Everest.

During the 1920s and ’30s, Nepal was firmly closed to outsiders, so British climbers aspiring to summit Everest had to endure long overland marches north out of \Darjeeling into Tibet, then west to the mountain’s base camp near the Rongbuk monastery and nearby glacier. Those long approach marches were important testing and warming-up times, ahead of the more strenuous technical ascents. Mountaineers’ books from this period are replete with rich descriptions of the countryside, the people, the cultures, and the foibles and eccentricities of the climbers themselves.

In 1934, Shipton invited Tilman to join him on an expedition to Nanda Devi, in India’s Garhwal where, together, they became the first recorded Europeans to cross the Rishi Gorge into the Nanda Devi Sanctuary. Nanda Devi hooked Tilman on the Himalayas. The following year he joined Shipton on a reconnaissance of Mount Everest (from the north), then returned to the Garhwal in 1936 to lead the first ascent of Nanda Devi (7816 m/25,643 ft). It was a feat that Tilman’s biographer Tim Madge calls “the greatest personal triumph in his climbing career.”

While higher elevations had been reached by others on Everest, Tilman’s and Neal Odell’s first ascent of Nanda Devi set a summit record that lasted 14 years until the French topped Annapurna-I at 8091 meters (26,545 ft) in 1950. In 1938 Tilman was back on Everest again, leading an expedition on which he and three companions climbed even higher than Nanda Devi. They did it without oxygen, reaching 8320 meters (27,297 ft), a mere 528 meters short of the summit.

With the outbreak of World War-II in 1939, Tilman put his climbing aspirations temporarily on hold. He rejoined the British Army and saw action in both Europe and the Mideast (Iraq). Afterward he was back climbing, this time to the Hindu Kush in 1947, Central Asia in 1948, and Nepal in 1949-50. He describes the Nepal adventures to Langtang, the Annapurnas and Everest in his classic book, Nepal Himalaya.

The Opening of Nepal...

In the late 1940s Nepal began to relax its long-standing ban on foreign expeditions. In 1948, for example, the Rana government allowed the noted ornithologist, Sidney Dillon Ripley, to lead two bird hunting expeditions in the lower mid-hills. He wrote about them in National Geographic magazine and in The Search for the Spiny Babbler (1953). Ripley was an ornithologist first and foremost, to whom the necessary trekking was incidental, so he wrote very little about the track and more about what he saw flitting through the bushes and trees.

In contrast, Tilman’s writings about mountaineering are closer to the ground, full of trekking lore.

Tilman was lucky. He applied for and quickly got permission to lead an exploratory and scientific expedition in 1949 to the north of Kathmandu into Langtang,. A year later, in 1950, he headed an even more ambitious expedition to the Annapurnas. Both were trekking firsts, requiring long cross-country walks out and back. And both were done in the monsoon, which often found the climbers wet and miserable.

Besides the weather, his Langtang and Annapurna campaigns, as he called them, were disappointments for their lack of serious climbing. In Langtang he and his companions reached only one minor summit, Paldor Peak (5896 m/19,344 ft), near Ganesh Himal. On the Annapurna trip, his team of experienced climbers attempted the higher and far more difficult Annapurna-IV (7525 m/24,688 ft). Given his age, however (he was 52), it was Tilman’s last high peak challenge. How he wrote of it shows off his talent as a writer.

On June 19, he says, he set out with three companions from their high camp, upward through the snow toward the summit of A-IV for a third and last try at the summit. Two earlier attempts had been thwarted by bad weather. On the way up, Major J.O.M. ‘Jimmy’ Roberts complained of freezing feet and turned back. Then, Tilman himself gave up, reluctantly, admitting personal disappointment due to “the combined effect of age and altitude.” That left Charles Evans and Bill Packard to make for the summit before the weather socked in. But they also soon turned back. “Evans had shot his bolt,” as Tilman described it, “and Packard, who felt strong enough, was rightly loath to tackle single-handed the last 600 ft. of steep and narrow summit ridge. Thus a fortnight of hard work and high hope ended in deep disappointment.”

Tilman then sums it all up as “a failure accounted for only by the more prosaic reason of inability to reach the top” (my emphasis). No excuses, they couldn’t do it. Full stop!

On a personal note, he concluded that chapter of his book with sad disappointment in place of his usual light-heartedness. “However well a man in his fifties may go up to 20,000 ft.,” he wrote, “I have come regretfully to the conclusion that above that height, so far as climbing goes, he is declining into decrepitude.”

On into the Khumbu...

The Annapurna trip was Tilman’s last climbing expedition, a not-so-grand finale to a celebrated career. In Nepal Himalaya, however, there’s one more story about a purely enjoyable trek with no high peak to climb. In September 1950, Tilman joined Charles Houston to reconnoiter a possible southern route through Nepal to the base of Everest. As Tibet was now closed, members of the world fraternity of hopeful climbers were eager to find an alternative route to the mountain. The Khumbu route needed exploring.

Houston, Tilman and three other companions began their westerly cross-country trek from Dhankuta in Nepal’s eastern hills. Their route took them up the Arun river valley and across the Salpa La into the valley of the Dudh Khola (Milk River) and on to Namche Bazar at the heart of Sherpa country. Tilman was quite taken with the Sherpas whom he had known from his climbs. Now he was delighted at last “seeing Sherpas, as it were, in their natural state.” But, once they reached the vicinity of what is now EBC (Everest Base Camp), and began looking for possible routes up Everest, they were disappointed. A way up through the Khumbu Icefall into the Western Cwm and on to the South Col looked “not very attractive,” as Houston vaguely put it. They felt that it was probably impossible.

It took Shipton’s British reconnaissance of Everest from the south a year later, in early 1951, to decide that the Icefall certainly posed difficulties but seemed feasible. In May 1953, Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary of the British Mount Everest Expedition proved them right, on the ninth attempt to summit Everest over three decades (since the 1920s).

Tilman in Retrospect

Tilman set the stage and his writings about trips in Nepal in 1949-1950 are a pleasure to read. They demonstrate his obvious joy of trekking and his careful attention to detail, while ambling along through villages, farm fields and kharkas (high sheep and yak pastures); while hiking through forests of pine, hemlock and silver fir, and of maple, oak, and rhododendron; and while walking the ridges and crossing high passes with their inspiring vistas.

Today, Langtang, the Annapurnas, and Everest rank among the most favored trek destinations in Nepal, and Paldor Peak is one of the most popular Trekking Peaks.

Tilman’s seven mountain books have firmly established him as “arguably the finest travel writer of the twentieth century”, according to the Everest climber and Tilman admirer, Bob Comlay. Written in Tilman’s detailed and ironic style, highly informative, opinionated, and often funny, they leave the reader in awe of this observant but modest outdoorsman. In Nepal Himalaya we learn about routes taken, gear used, food eaten, people met, and issues with the weather. As his last mountain book, it was a turning point in mountain-travel writing, one that reveals a great deal about early trekking in Nepal. It is dated, but informative, entertaining, and still useful today, for Tilman’s explorations and writings were on the cusp of modern trekking in Nepal. If you count the pages in Nepal Himalaya, you’ll find that there are more on the pleasures of trekking than on climbing. But, it was his last, after which he took up sailing. He disappeared on the high seas of the South Atlantic Ocean in 1977. He was 79 years old.

For adventurers, Tilman gave us historically important notions about early trekking. For travel writers he set a high bar, at once serious, funny, curious and sardonic. Here are a few examples:

Sage advice... “At the beginning of such a journey,” Tilman once wrote, “one should, of course, be on fire to start, the feet tingling to treat the trail, the back itching for its unaccustomed load, a fierce contempt for motorcars uppermost in one’s mind.”

When asked how to start such an adventure, he said: “Put on a good pair of boots and walk out the door.”

On boots and ‘parris’... Tilman and his companions brought two kinds of footwear to the Annapurnas, the old fashioned nailed boots that had been the mainstay of mountaineers for decades, and the new molded rubber ‘Vibram’ type that were new in popularity. This suggested to him that he and his companions “wished to move with the times” but without “enough confidence in the new to discard the old. For rough walking,” he wrote, “the ‘Vibram’ soled boot is more comfortable than the nailed. It is supreme for that everyday Himalayan pastime of boulder-hopping (provided the boulders are dry), and is generally suitable for climbing except on wet rock, wet ice, or fresh snow on rock. It is a matter of taste,” he concluded. The Vibrams “are as good as nailed boots and sometimes better.”

And sometimes not, for he also wrote that on trails “slimy, slippery and half overgrown after months of rain” the Vibrams may present “the unwary with many opportunities for misadventure.” They were most dangerous, he discovered, when crossing ‘parris’ clinging precariously to canyon walls along roaring rivers. ‘Parris’, which are not much seen any more, were made of narrow planks, poles or tree limbs laid across posts driven straight into cracks on a cliff wall, or held up from below by tall poles well anchored. The cautious traveler used them to traverse a river gorge directly, rather than clambering up and down, far and high to avoid the cliffs. Some ‘parris’ he encountered were “greasy enough to warrant the strewing of a little sand for those misguided enough to wear rubber-soled boots.” Very slippery. Very dangerous. Very scary.

On ‘bummelling’ along... To ‘bummel along’ means to move at a leisurely pace, on a journey, long or short, seemingly without an end. Tilman used the term while describing the terse notes he normally took (from which, later, he wove his stories)—

“But man is a creature of his environment. However reasonable and true such ideas are to a man seated in a chair, they take on a different hue when the same man is ‘bummelling’ along the tracks of Nepal. Witness the notes made of one march—‘up a steep narrow track, like walking in a sewer, 500 stone steps up to Samri—no view—2000 ft. down—hellish steep and rough track—porters slow—no view—no bananas—no raksi’. The broken nature of the country seems to have struck the writer as an offence and the absence of food and drink as a stumbling-block.”

.jpg)

On food and drink... Writing of conditions well before the modern popularity of teahouse trekking with menus loaded with gastronomic enticements, Tilman reported that –

“In Nepal one can live off the country in a somber fashion, but it is no place in which to make a gastronomic tour. There are no wayside shops as in Sikkim where one can drink sweet tea or sip maize beer through bamboo tubes; no hospitable villagers who in Tibet dispense buttered tea and blood and buckwheat cakes as a matter of course, no yorts overflowing with cream, yoghourt, and hot barley bread as in Sinkiang; and no apples, pears, peaches, apricots, fresh or dried, such as one stuffs oneself with in Hunza. May, of course, is a bad month for fruit, but outside the valley [of Kathmandu] there is little to be had except bananas and small oranges.”

Be glad you are trekking nowadays, though sometimes there’s no rum or raksi or chang to assuage one’s thirst.

On “profound emotion” inspired by (lack of) raksi or rum... What do you do (on trek) when things don’t go your way. Tilman, in good humor, used clever verse.

Somewhere in the hills between Dhankuta and the Khumbu, on the 1950 trek to Everest, Tilman went looking for a drink of rum or raksi (rice wine), and was skunked. So he turned to doggerel. From a campsite on rice stubbles near the village of Gudel, the party could see “across an appallingly deep valley” to the village of Bung. There, they hoped to find something to drink—

“Bung looked to be within spitting distance, yet the map affirmed and the eye agreed that we should have to descend some 3,000 ft. and climb a like amount to reach it. Profound emotion may find vent in verse as well as in oaths; despair as well as joy may rouse latent, unsuspected poetical powers. Thus at Gudel uninspired by liquor, for there was none, some memorable lines were spoken:

For dreadfulness nought can excel

The prospect of Bung from Gudel;

And words die away on the tongue

When we look back at Gudel from Bung.

“The village of Bung, a name which appeals to a music-hall mind, provoked another outburst on the return journey because its abundant well of good raksi, on which we were relying, had dried up.

Hope thirstily rested on Bung

So richly redolent of rum;

But when we got there

The cupboard was bare,

Sapristi. No raksi. No chang.”

On packsacks... The pack-boards Tilman used in the Annapurnas “were massive structures of the Yukon type, built evidently for professional packers, old timers, ‘forty-niners’, and such like, men who could ‘take it’ in every sense.” Though they weighed nine pounds, empty, the expedition Sherpas and local porters (he called them ‘coolies’) “grew fond of them. Provided the canvas back is kept really taut they make a very comfortable load.” Then, rather wistfully, he added that “a lighter type made of plywood should be excellent.”

Tilman was unaware that a man in California named Dick Kelty was inventing a revolutionary new, strong, light-weight backpack. The ‘Kelty Pack’, first marketed in 1952, owed its strength, comfort and lightness to its aircraft-aluminum contoured frame, padded shoulder straps, waist belts, and a roomy bag made of nylon cloth. It didn’t take long to replace the bulky Yukon pack and its lesser cousin, the Trapper Nelson.

On the weather... For both climbers and other “folks that go a-pleasuring”—we trekkers, that is—Tilman advised avoiding the monsoon, which gave him a lot of soggy discomfort. But since one does not always have perfect control over “the ideal time” he concluded, “the party goes out when it can and returns when it must.”

And about those lost dentures... “As Don Quixote observed, a mouth without molars is worse than a mill without stones. The others [on his Annapurna trip] with fully equipped mouths had no complaints, indeed rather liked the biscuits.”

———————————————

“We had climbed a mountain and crossed a pass; been wet, cold, hungry, frightened, and withal happy. Why this should be so I cannot explain, and if the reader is as much at a loss and has caught nothing of the intensity of pleasure we felt, then the writer must be at fault. One more Himalayan season was over. It was time to begin thinking of the next. ‘Strenuousness is the immortal path, sloth is the way of death.” (Tilman)

Trekking Peaks of Nepal

The practice of identifying and promoting ‘Trekking Peaks’ as an alternative to over a hundred more technical alpine peaks, came about in 1978 when the Nepal Mountaineering Association (NMA) was formed. At first, 18 peaks requiring a simpler permit system and lower costs were opened for foreign climbers. Since then, another 15 peaks have been added, for a total of 33. The term ‘trekking’ peaks is a bit misleading, because all involve climbing, and some are technically quite challenging.

The NMA identifies two types of Trekking Peaks: 15 Group ‘A’ Expedition Peaks, and 18 Group ‘B’ Climbing Peaks (see www.nepalmountaineering.org.) All 33 fall between 5650 and 6500 meters (18,357 to 21,325 feet). For rules regarding permits, group size and costs, see the NMA website, and the websites of commercial outfitters (Google ‘Trekking Peaks Nepal’). The peaks are located in specific climbing regions, east to west, in Kanchenjunga, Khumbu/Everest, Rolwaling, Langtang, Manaslu, Manang, Annapurna and the Annapurna Sanctuary.

Some of the Group B-Climbing Peaks are quite popular, including Tilman’s Paldor (5896 m.) in Langtang, and both Mera (6470 m.) and Island Peak (6160 m., also called Imjatse) in the Khumbu. Some Group A-Expedition Peaks, notably the Khumbu’s Phari Lapcha (6017 m.) and Cholatse (6440 m.), attract more experienced climbers because of their technical challenges.

Trek, Trekker, Trekking

A trek is a long and arduous journey or expedition, especially one made on foot or by inconvenient means. The term originated in South African in the 1800s, from the Dutch (Boer) trekken, ‘to draw’ (pull), in reference to traveling by ox-drawn wagon. Only in the past half century has it been generalized to mean any slow and laborious travel.

Tilman rarely used the term ‘trek’ (twice) or ‘trekker’ (once) in his seven mountain books, though not at all in Nepal Himalaya. He was a pioneer trekker ahead of his time.

In the Himalayas, a trek is an extended walk in the mountains, by a ‘trekker’—an ambitious hiker or rambler. Trekkers are also sometimes called ‘trekkies’ (not to be confused with those avid fans of the popular TV series, ‘Star Trek’). ‘Trekking’ is the preferred mode of travel by adventurous visitors to Nepal, where ‘trek tourism’ is a big business.

Books by H.W. ‘Bill’ Tilman

1937: Snow on the Equator

1946: The Ascent of Nanda Devi

1946: When Men and Mountains Meet

1948: Everest 1938

1949: Two Mountains and a River

1951: China to Chitral

1952: Nepal Himalaya

All seven books in one volume:

The Seven Mountain-Travel Books (Seattle: Mountaineers, 1983)