To Ink or Not to Ink

"Tattooing was the cheapest way to adorn oneself with un-erasable jewelry," said Kanni Devi Tharuni from Saptari when I asked why she had tattoos all over her body.

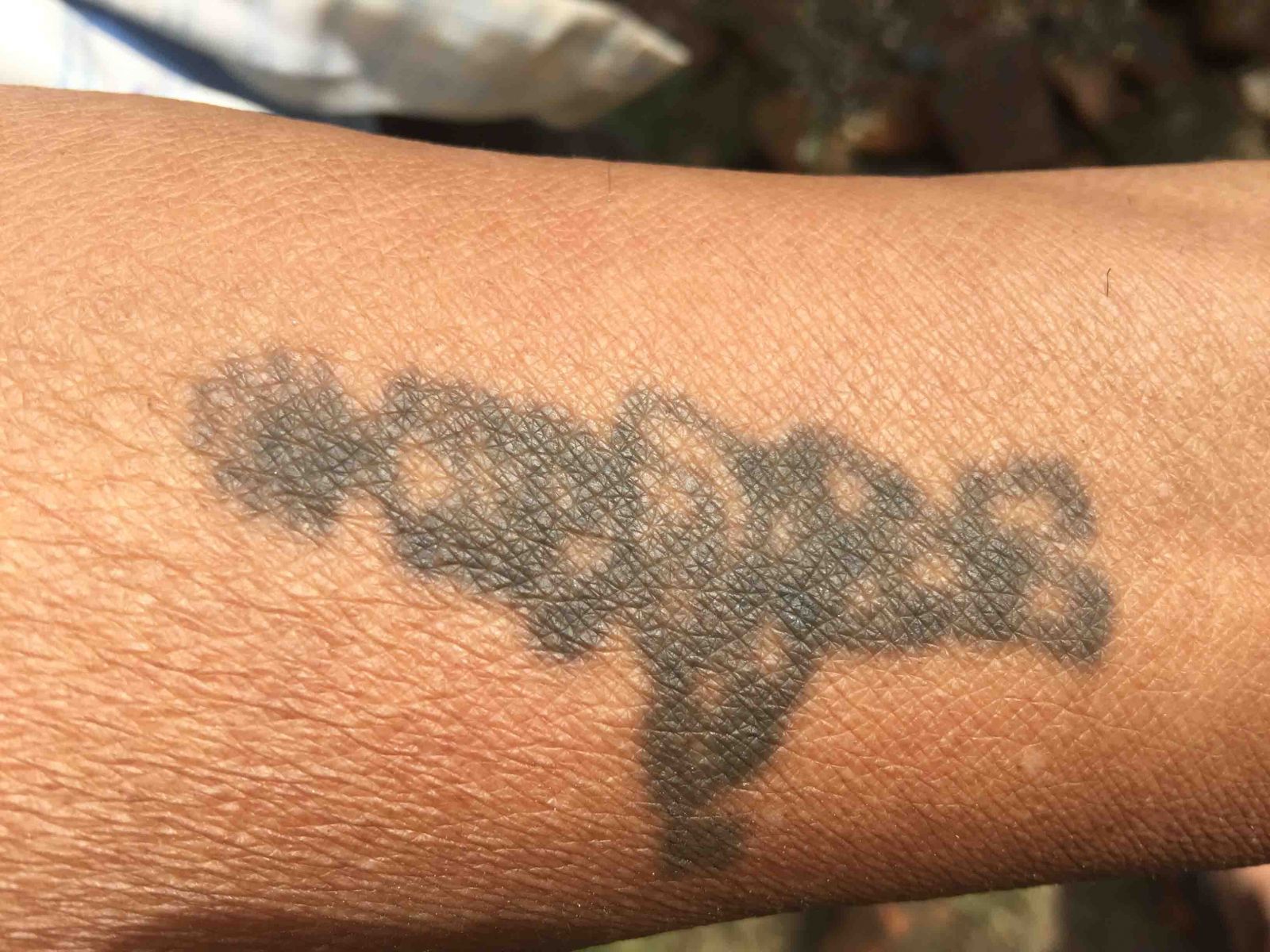

The Tharus in the southern plains of Nepal had a rich culture of wearing tattoos on their bodies. Tharu women used to get tattoos on their arms, legs, and chests to look more beautiful. The tattoos, called khodna and godna in the Tharu language, were inspired by nature. The most common motifs to be tattooed were lines, dots, crosses, and several other natural elements. The most common and complicated tattoo is that of a peacock. Women even braved to get tiger tattoos on their chests. Tharus in eastern Nepal have interesting names for the tattoo patterns—badam butta (groundnut), suraj ke daali (rays of the sun), and thakari mutha (a handful of hair combing materials), among others.

While the tattoos were worn as permanent jewelry and optional for young women, it was compulsory for married women to get tattoos on their legs. They used to get tattoos on their legs prior to marrying, generally in the month of March (Falgun/Chaitra in the Bikram Sambat calendar).

Tattooing used to be painful and gruesome. The tattooers, called tikaniyas, used tattooing needles and natural black ink obtained from the soot gathered from a lamp. The process used to be slow, and sometimes the person receiving the tattoo even fainted. The body part to be tattooed was rubbed with cow dung and later washed well with water. After drying, mustard oil was applied to make the surface soft. The tikaniya would then mark the designs and prick the skin with tattooing needles.

Once practiced by tribals and indigenous people, the tattoos were hated by the nobles, and it was one of the reasons why the Tharu women in Chitwan got tattooed. It helped them avoid the danger of being abducted and kept as sex slaves by the royals.

Kanni Devi said that she felt more beautiful with tattoos on her body, and nobody could steal the permanent jewelry. She said, “This tattoo will go with me to the next world when I die.”

In spite of the rich history of tattooing, the Tharu youngsters don't get tattooed at all. The old experienced tikaniyas are no more found in the villages, nor are there any takers who can steer this age-old tradition forward.

However, since tattoos have become a fashion statement these days, with safer, quicker, and easier technology, it’s the need of the moment to document the tattoo patterns worn by old Tharu women. Modifying the traditional motifs and using multi colors, instead of plain black ink, will be crucial in keeping the age-old tradition alive.