Author: R.R. Jordan, Publisher: Giridhar Lal Manandhar

I am, and have been since February, Resident Minister at this Court, the only independent one now left in India… But my situation is by no means so agreeable as it might be if these barbarians did but know their own good. Instead of which they are insolent and hostile, and play off on us, as far as they can and dare, the Chinese etiquette and foreign polity. The Celestial Emperor is their idol, and, by the way, whilst I write, the (Nepalese) sovereign himself is passing by the Residency in all royal pomp to go three miles in order to receive a letter which has just reached Nepal from Pekin.

There they go! Fifty chiefs on horseback, royalty and royalty advisers on eight elephants, and three thousand troops before and behind the cavalcade! They have reached the spot. The Emperor’s letter, enclosed in a cylinder covered with brocade, hangs round the neck of a chief; the Prince descends from his elephant to take the epistle, a royal salute is fired, the letter is restored to the chief, who, mounted on a spare elephant, is placed at the head of the cavalcade, and the cortege sweeps back to the capital.” Thus wrote Brian Hodgson, the then British Resident to Kathmandu (1833-1843) in a letter to his sister in England.

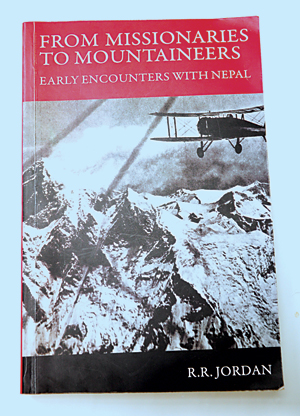

If this piques your interest, then there’s plenty more of such stuff in From Missionaries to Mountaineers – Early Encounters with Nepal, the author of which is R.R. Jordan, who first came to Nepal in 1965 to teach English at the British Council. He lived here for four years. Ever since, he started collecting books on Nepal and visited the country many more times. His growing interest in the country has resulted in this book, which is a collection of extracts and information from books and articles on Nepal written by travelers through the centuries.

If this piques your interest, then there’s plenty more of such stuff in From Missionaries to Mountaineers – Early Encounters with Nepal, the author of which is R.R. Jordan, who first came to Nepal in 1965 to teach English at the British Council. He lived here for four years. Ever since, he started collecting books on Nepal and visited the country many more times. His growing interest in the country has resulted in this book, which is a collection of extracts and information from books and articles on Nepal written by travelers through the centuries.

Arranged chronologically and, in some places, according to theme and topic, it does not claim to be historical in nature, but illustrates the experiences of the first Westerners (missionaries, traders, soldiers, diplomats, hunters and plant hunters, royalty, explorers and mountaineers) to visit Nepal. In this day and age when reading anything original has become somewhat of a rarity, this book comes as a breath of fresh air. Straight from the horse’s mouth, so to speak!

Jordan has taken some pains to include as wide a variety as possible of writings by different people so as to give a better picture of things as they were once upon a time in the mystical Kingdom of Nepaul. For those interested in etymology, too, it is quite interesting to see how the same words keep on changing in the course of different accounts. And so we find that Gurkha was once spelt Goerha, then Goorkha. Similarly, Kathmandu is spelled variously as Catmando, Khatmandoo and Khatmandu in different accounts.

Of course, more interesting are some of the firsthand accounts such as the one by Sir Henry Lawrence on November 5, 1845: “I have just returned from a Suttee (self immolation of a widow at her husband’s pyre)… a terrible sight but less so than I expected…”, and Dr. Henry Ambrose Oldfield’s witnessing of an execution, “A sepoy, a Khatri, having committed a murder… was sentenced to have his head cut off… executions always take place on Tuesdays and Saturdays, as unlucky days…” Both the abovementioned accounts go to some length to describe the events in detail. Fascinating reading, no doubt!

A lot of space has been given to Maharaja Sir Jang Bahadur, who is often referred to in the familiar term as just ‘Jang.’ And there are quite a few accounts of hunting expeditions with meticulous listing of the bag for the day (i.e. number of tigers, rhinos, deer, etc. killed during the hunt). The explorations of famed botanists like Hooker should be of great interest for those so inclined, and the accounts of initial surveys done of the country, too, are quite informative. As expected, the exploits of the Goorkhas make for a substantial part of the book with some writers (mostly military officers) literally going overboard in their praise.

But, while there is much admiration evident from the accounts about Nepal and its people, there are some derogatory ones, too, such as this one by Surgeon-Major Dr. Daniel Wright in 1877, “… from a sanitary point of view, Kathmandu may be said to be built on a dunghill in the middle of latrines”. The description is echoed by the American, Henry Ballantine, who wrote “… a most picturesque appearance outwardly, but inwardly reeking with filth; a city which has dunghills for its foundations, stagnant pools for ornamental lakes… where the widest thoroughfares are narrow lanes. Such is Khatmandu, with its ever present effluvia and stench…”

This was written in 1855. Has much changed in the 155 years thence?

More than just your usual lapel pins

The lapel pin is a men’s accessory worn on the lapel of the jacket which serves as a...