One of my favorite memories from my childhood in the Terai is of the sight of the first monsoon rain that arrived from the south. After months of relentless heat that turned my hometown into a ghost town in the afternoons, the gales that swept up dust clouds ceased, the sky grew darker, and the earth became cooler. Then, first visible as a great white diaphanous wave, the monsoon rain appeared on the southern horizon, emerging from behind the green wall of a sal forest to spread across the parched land. That sight of the approaching rain made us feel as though we had shed a heavy layer of skin from our bodies. Rain meant liberation from the oppressive heat.

The wait for the monsoon, especially if you were a kid, was torturous. And the last few clammy days leading up to the first shower were unbearable. At night, we slept on our terrace to escape the heat, slapping ourselves while trying to get at the mosquitoes, scanning the starry heavens for constellations and satellites, too hot to indulge in thoughts. To console my sister and me (both of us writhing and voicing our discomfort) my grandmother would tell us that rain was imminent since the frogs were croaking. This was late 1980s Kanchanpur district of western Nepal, where at the blowing of the slightest breeze the power went out—sometimes for up to ten days. After a while it made more sense, even to us kids, to inquire about the arrival of the rains rather than that of power. The only time in my life I disliked rain was during my years in a boarding school in a hill station in India, where rain meant staying indoors while all I wanted to do was go out and play. Otherwise, my heart – and perhaps that of every child in our town – leapt up as the first monsoon raindrops fell.

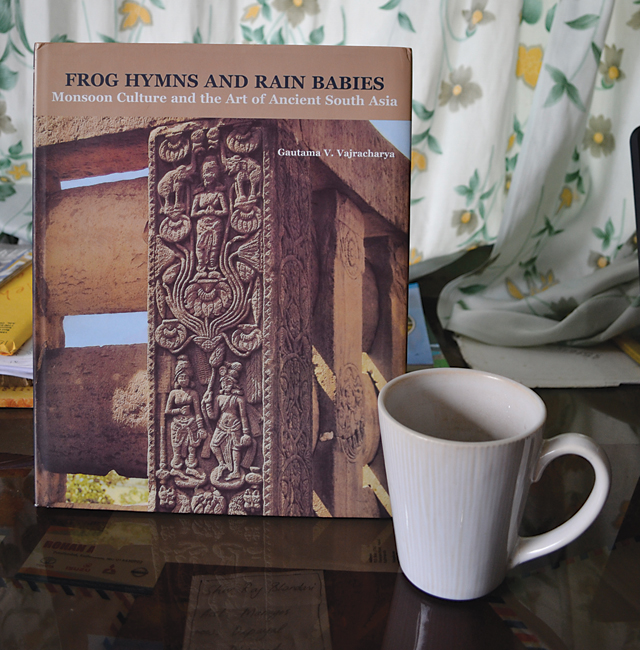

Gautama V. Vajracharya’s book Frog Hymns and Rain Babies: Monsoon Culture and the Art of Ancient South Asia evokes such memories. Actually, it evokes the collective memory of the Indian Sub-continent. His work, above all, reminds readers that the elation people feel at hearing frogs croaking and rain clouds swelling has remained unchanged, albeit reduced in intensity, since the fields of the first farmers of the Sub-continent were soaked by the monsoon.

The book is a lengthy but riveting elucidation of Vajracharya’s thesis that it is this timeless dependence of the Sub-continent’s populace on the monsoon rain that has shaped its religion, literature, art, and architecture. “Ancient India, indeed, thought primarily in terms of rain and drought,” Vajracharya writes in one place, and it is this way of thinking that he has adopted as his way of looking at the art of ancient India. Pratapaditya Pal, the eminent art historian, in the foreword to the book, has described Gautama Vajracharya’s work as an unprecedented attempt to give “serious consideration to the impact or influence of this natural phenomenon [the monsoon] on the Indian mind…in the light of Sanskrit and ancient Indic art.”

When Vajracharya, whose schooling up to the secondary level was in Sanskrit, examines Sanskrit texts and ancient South Asian art (with his monsoon “glasses” on), he is able to infer clues other scholars have missed or misinterpreted because of the language (Sanskrit) barrier. He almost seems a man on a mission to prove that the art and literature of ancient South Asia (and of the Kathmandu Valley) are celebrations of the monsoon rain. And prove it he does. The depth and variety of the evidence – sacred Vedic texts, poems, treatises on drama and architecture – and its presentation in the lucid style of a seasoned logician (which the author is), makes his thesis hard to refute and the book hard to put down.

The book contains the author’s studies of such famous religious and historical sites as Sanchi, the Ajanta caves, and structures such as the Ashokan pillars. He identifies in these representations of the monsoon. The ceiling paintings of Ajanta, Vajracharya explains, are artistic depictions of the sky and rain clouds; the Ashokan pillars and the animals on them, according to him, are allusions to the annual descent of rain from the skies. He even takes something as simple as an earthen pot, elucidates on its design and then, as though it was obligatory, traces the pot’s design to the monsoon culture.

The last three chapters focus predominantly on the art and architecture of the Kathmandu valley. Vajracharya relishes in pointing out evidences of the monsoon culture that still survive in the Valley several centuries after they were forgotten in India. He points out that the significance of the makara and the turtle, two animals that disappeared from Indian art several centuries ago, is still understood in Nepal.

It is facts such as these that make Frog Hymns a must-read, or better, must-have for anyone interested in the art and architecture of the Sub-continent. Its value for Kathmanduites, or those seeking to better understand its art and architecture, is even more.

It is a circuitous trip that Frog Hymns takes us on. But the beauty of the trip, like the beauty of the monsoon, is in the arrival. In this case, for those of us from the Sub-continent, that arrival will most likely be of our childhood memories.