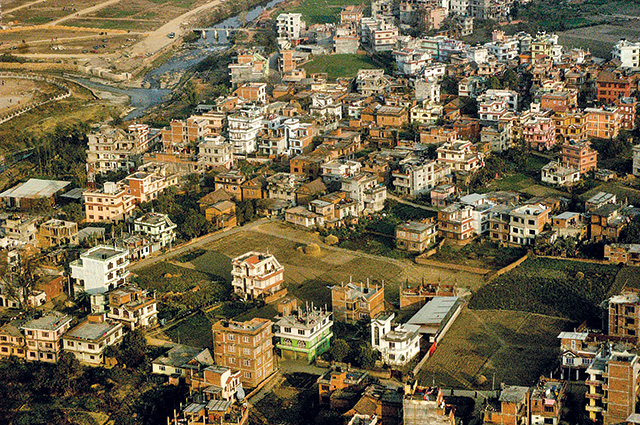

Furtively, I wiped the window with a tissue; not a smudge must impede my vision. The Big Show is outside. Alerted to choose a seat on the right of the plane so I could see the Himalayas, I was ready with my camera. Multiple snow-capped peaks posed as candidates for Everest. I wasn’t sure which was the real thing, but I was confident to have caught a few “prime suspects.” I thought the show was over. As I was putting my camera away, I suddenly spied the steep steppes of spectacular green and yellow-green farm fields east of the city. A Grand Finale began. In rapid-fire frames I captured the menagerie of slender three-storied apartment buildings rising like stalagmites from the plains of the Kathmandu valley. How could I not think of my native Pittsburgh, whose hilly topography disperses the clapboard and brick houses in a chaos of colors and shapes?

I knew I was going to like Kathmandu.

I love houses. Even as a child, I built stone and mud “houses” between the knuckled surface roots of my elm trees. I fabricated wood models; I built furniture. So you can understand why the textures of Nepali domestic architecture: carved columns and beams, burnished red bricks, stone pedestals, and wood thresholds, and those secret metal markings of the Newars, totally transfixed me. Like a song that won’t quit your heart, I could not excise these buildings. I had to see them again. Of course, I feared how the April earthquake had shaken these beauties.

Whether one enters this beautiful Nepali world through the intimacy of a village house or the grandeur of durbar squares is personal. There is a subtle interplay between private domestic architecture and the grand public forms. The riddle of the chicken and the egg! Whichever came first, one will lead to the other.

Whether one enters this beautiful Nepali world through the intimacy of a village house or the grandeur of durbar squares is personal. There is a subtle interplay between private domestic architecture and the grand public forms. The riddle of the chicken and the egg! Whichever came first, one will lead to the other.

I began the “pubic way.” I explored Patan Durbar Square the first morning. Suddenly and expansively, the fully elaborated system of Newari architecture was set before me. We stood at a lookout near the palace with Hanuman wrapped in red. I spied the cupola-like “fucha” atop our perch. “What is that?” I asked myself. “A Nepali version of a ‘widow’s walk’?” A quick survey of what we were about to walk through assured me that even in a valley, a mountain goat’s path is going to be fun to follow. What delight I took in the handsomely-carved black lintels that made me lower my head in humble submission to their beauty. Everywhere, texture and improbably rich ornaments! This architectural feast was like three chocolate cakes, a cream torte, a lemon meringue pie, and two dishes of ice cream, and with berries.

I kept being intensely distracted from the path I needed to follow: ornately carved temple roof struts here, brass griffins atop a stele there, those spreading eagle wings of lintels over the windows and doors, the crowds of people feeding pigeons, statues of Ganesh and Vishnu making street-level epiphanies without a vendor’s license! The finely screened upper balconies of the broad “houses-of-the-gods” temples made me, a cabinet maker, wonder how they were assembled. Handsome men and beautiful women marked their foreheads with “tika.” It probably helped that my tour guide disciplined my eyes by making a forced march through the durbar square.

Curious, yet embarrassed, observations in Pashupatinath corroborated the few bits of architectural knowledge I had of Himalayan architecture. I compared the ubiquitous chaitya stupas to those I knew in Tibet. Funeral pyres smoldered on the podia, and the tallakara tiered temples rose up to snag the wisps of human incense. These glimpses of Kathmandu were introducing me to the architectural repertoire of the Newars. In time, I managed to visit Bhaktapur, Changu Narayan, Panauti, and Bungamati, places where one could see the best examples of Newari architecture. Yet, even while my foray into Newari architectural forms was still young, already I was beginning to make references back to the Chinese architecture I have been exploring for nine years.

In their respective “public forms,”, both the Chinese and Newars share a fondness for multi-tiered temples, courtyard houses, and intricately engineered and supported roofs. Consider the latter, for example. if you look up to the roof line, one has to be dazzled by the voluptuously carved Nepali wooden temple struts. How precarious their flying act must be! And yet they function in the same way as the martially rigid orders of the Chinese Dou Gong brackets. That they both serve the same function is obvious, but how wildly different in form. Or, to take another comparison: at the entrances of Newari buildings, I noted two great differences. The columns (and door jambs) that carry all the weight of a Chinese building do not do the same in a Nepali house. Here, in Nepal, the walls do the heavy lifting. Indeed, the expansive blackened beams that crown the entrances to Newari buildings carry huge weights upon their shoulders; so do the horizontal face beams of the Chinese temples. But, the latter stretch end-to-end across the whole face of those temples, while the Newari door lintels have the elegant task of forming an iconic “crest.” Having seen one Newari door or one window lintel, the image is fixed forever. Inside a Newari temple, one cannot but compare its rectangular courtyard to the four-sided courtyard houses of the Han Chinese. Indeed, for the Chinese, this “siheyuan” is the paradigm for both temple and peasant house.

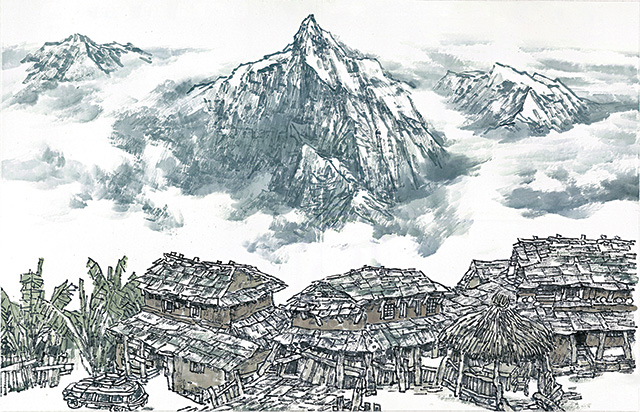

Once the public spectacle of the towered temples, palaces, and Boudhanath stupa had firmly formed their mountainous musical “continuo” in my mind, it was a set of tiny intimate “melodies” that began to reassert themselves: the subtlety and beauty of the houses of Nepal. They are mud brick and blue, crawling over impossible steps, faced with broad porches, sometimes graced with broad carved lintels. They are so human. This is the emotional tug that attracts me to Nepal. It is the same tug that generates the intimate textures of Zhao Jianqiu’s great yet humble drawings. In fact, he invited me to return to Kathmandu so that we could share our delight in the densely woven fabric of Nepali culture.

As I was preparing my architecture lecture notes to celebrate the opening of Zhao Jianqiu’s exhibition at the Nepal Art Council, I naturally returned to my first photographs of Kathmandu. I was Photo-shopping out the haze in my “landing” photos, when I was startled to see something nestled among the circus of self-important concrete buildings. Almost hidden in my photos with their mud-color, I spied “hip and gable” houses. What were they doing here? I had to come back to find them in person. So, on this return trip to Nepal, I rove the alleys and avenues of the Kathmandu valley looking for these houses. You probably know them like the back of your hand. For me, they are a startling discovery, because such a form does exist in China, but only in the Imperial City. Only the “royals” can have this house form. So I had to find out why they are sprinkled all over the valley.

Not surprisingly, I found these “hip-and-gable” houses in Zhao Jianqiu’s ink drawings too. He too must have a fondness for them. There they are, distinctive but as familiar as a farm house; elegant, but not ashamed to be made of thatch and mud. See if you can find one in the great expanse of the Bhaktapur drawing. They star in “Passing by Pokhara” and take a bow in “Contented Life.”

But, more than these architectural “types”, there is something more charming that endears Zhao Jianqiu’s painting to me. He takes meticulous delight in the simple traces of human beings’ presence. You may see no one in his fields, you can hardly distinguish the faces on the porch, but you know just what kind of person has been there. Over-loaded cars and toppled chairs, a forsaken wicker basket, a tiny flag, a well-worn path. All is evidence! But, perhaps the most playful human evidence of all is how Zhao Jianqiu has carefully re-arranged the markers of a plaza, nudging a chaitya to the right, removing an obstacle to an untrammeled vista… Zhao Jianqiu has b een here! But there is no picture of him. Just his evidence.

The earthquake entombed 9,000 sacred spirits. Whole villages mourn their absences. But they left traces too, their spirits had marked doorways and window sills. Even in the scattered debris of their collapsed houses, we find evidence of this human presence. All is not lost. In fact, their traces will form a new layer of meaning to life once lived and life now new in Nepal.