In the privacy of our minds, we all talk to ourselves - an inner monologue that might seem rather pointless... But the act of giving ourselves mental messages can help us learn and perform our best. -Annie Murphy Paul, ‘Talking to Yourself’

This is a column about words, though not all words are readable, printed or even printable. Some are only audible, and at times only imagined. We often talk to ourselves, seriously, for self-guidance or encouragement to get over something difficult. It helps confront the unknown or the unforeseen.

I heard words in my ears recently while negotiating an unusual and dangerous bridge over the Kali Gandaki river in a blustery rainstorm:

I heard words in my ears recently while negotiating an unusual and dangerous bridge over the Kali Gandaki river in a blustery rainstorm:

You can cross this thing, I heard. Just don’t look down.

One step at a time. Careful now. Avoid that wobbly log. Keep your balance. Don’t slip.

One section done, now do the next. Slow. Steady.

Don’t get blown off this * thing...! (expletive deleted). Stay the course...

They were audible, encouraging, cautioning, complementing words, urging me on.

Just a little more now...

Ah, finally, the end is in sight.

The unfinished bridge abruptly terminated atop a pylon far from its intended conclusion. Wet and weary, my two companions and I had done it successfully and safely, though with some trepidation. It was an altogether extraordinary crossing.

We got down by a rickety wooden ladder.

Writers live on words, usually written down or typed. Orators and actors are good at mouthing them, and readers may say them off the page, aloud. At times we writers also talk to ourselves, to test a phrase or find the right verb or adjective, for example. We hear ourselves muttering along while muddling through a rough draft or when facing a challenging passage, be it a narrative passage on paper or a physical passage over a raging river. No matter; words help us contemplate, fix, balance, reconsider, take the next step, and move on. Finish one section. Confront and conquer the next.

I clearly heard a voice, my voice, recently while crossing the remarkable Kobang Bridge in Thak Khola. It’s not your typical suspension bridge, but a long elevated track that requires walking cautiously for a long ways on three parallel beams 12 feet off the ground, or above the water. Each log is about eight inches wide, squared, and insecurely laid side by side from one T-shaped concrete pylon to the next. We crossed close to 20 sections, each roughly 24 feet long. There were no handrails, and we soon discovered that some of the beams wobbled precariously under foot.

Crossing in wild storm conditions we had trouble keeping our balance, so we didn’t stop to measure anything accurately, or take photographs. My companions and I simply wanted across and off as quickly as possible.

We all talk to ourselves at times like these, when facing a new or difficult task, or confronting something scary or dangerous. We do it to deal with the unfamiliar, to assure ourselves.

Scientists who have studied the phenomenon have identified three stages in ‘talking to ourselves’, three cycles of wordiness. The first is forethought, when we set a goal and make a plan. Performance follows, as we carry out the plan. Then self-reflection, when we evaluate our accomplishment. In other words, we contemplate something coming up, then confront and deal with it head on, then look back in retrospect, and sometimes in awe. It’s the same for writing an inspired essay as it is for crossing an insecure bridge.

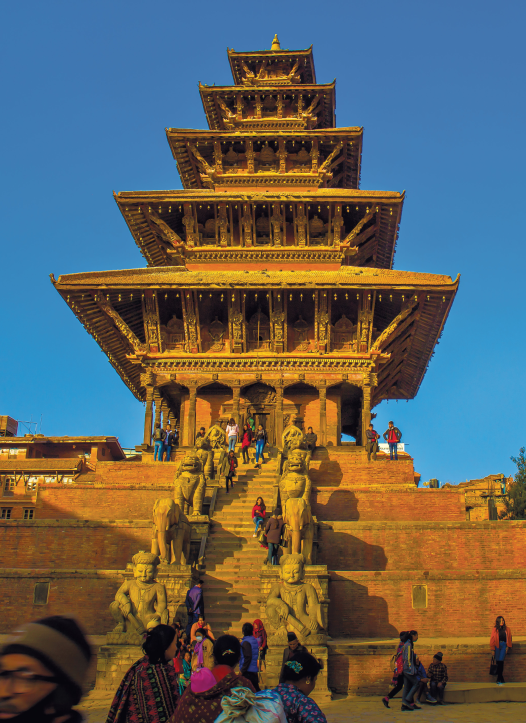

The Kobang Bridge spans the Kali Gandaki in the valley of ‘Thak Khola’, where the great river cuts through the Himalayas separating two of the world’s highest peaks, Dhaulagiri and Annapurna. The scenic geography, the history and the perceived sanctity of the region have made this a popular trek destination as well as a sacred quest for Hindu and Buddhist pilgrims. It’s a dramatic walkabout to talk about and write about.