Someday I’ll be the artist formerly known as starving.

(Fred Babb, contemporary American artist)

At the London home of Nepali artist

Lain Singh Bangdel, late 1950s −

She’s a connoisseur of art, and she’s rich,” said Manu’s friend. “She might want to buy one of Lain’s paintings.”

The ‘connoisseur’ called herself a ‘baroness’ and claimed to be an upper-class refugee from some eastern European country. A friend brought her around one weekend to Lain and Manu’s north London flat. In anticipation, Manu cleaned the tiny sitting room and Lain carefully put the best paintings out for viewing and his unfinished canvasses and rejects in a corner, out of sight.

The baroness smoked cigarettes in a long holder and spoke English with an affected British accent. Manu served tea while her friend and the baroness made small talk with Lain about art. Then Lain showed her the paintings, one after another. She seems unimpressed, uninterested. She liked none of them.

The baroness smoked cigarettes in a long holder and spoke English with an affected British accent. Manu served tea while her friend and the baroness made small talk with Lain about art. Then Lain showed her the paintings, one after another. She seems unimpressed, uninterested. She liked none of them.

The relationship between buyer and seller is almost as important to Lain as that between artist and sitter during a portraiture session. Nothing satisfied this lady, and Lain admits that he was a bit ‘put off’ by her manner and attitude about art. He felt nothing good in this relationship. “What could I say?” he asks. “That’s the life of a painter, you know.”

Then, as she was about to leave, the baroness saw the stack in the corner.

“What’s that?” she asked impulsively, and to Lain’s embarrassment and chagrin she began pulling them out for viewing, one by one, holding each one up to the light, turning them this way and that to see them better. She stopped at an untitled, unfinished painting of a Nepalese man looking down with his head in his hands. Manu says it reminded her of August Rodin’s ‘Pensuer’ (‘The Thinker’), the famous bronze statue the French artist had sculpted in 1880. The baroness fussed over the canvas and described the sort of frame that it must have.

Lain did not care about that, for by now he was annoyed and disinterested in anything the woman said.

“How much?” the baroness asked, waving her long cigarette holder in the air.

“Eight hundred guineas,” Lain mumbled, far more than he had ever asked for a painting! He thought it would put her off and that she would finally leave. Instead, she asked incredulously, “Are you suure?” in her contrived style of speech, as if the price was not high enough. Lain was astonished. Eight hundred guineas was a large sum for a painting by a relatively unknown artist.

“I want this painting!” she declared.

“It is unfinished,” said Lain, but that only seemed to strengthen her resolve. She was apparently used to getting whatever she demanded. She stubbed out her cigarette, dug into her handbag, counted out the cash and gave it to him, then rolled up the canvas and went out the door.

“It was incomplete,” Lain says, with a smirk. “I hadn’t even signed it. It was unfinished work, which I would have hardly sold for 160 guineas at the most. I have no idea who she was, just some wealthy lady.”

Some of the people Lain encountered in Europe amazed him.

un-fin-ished adj.

Incomplete or imperfect, fragmentary, partial, in progress, ongoing...

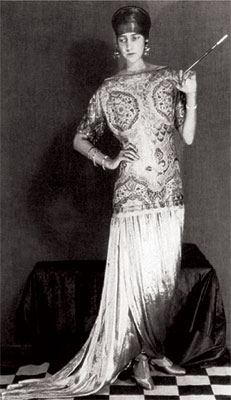

Author’s postscript : Unfortunately, there is no image of the painting he sold in the Bangdel archives. The rich baroness paid for it in cash and left no address. The painting is probably hanging unknown somewhere in Europe, now over a half century on. The image of the baroness, above, is how one might assume she looked.

Lain Singh Bangdel (1919-2002) lived in Paris and London for most of the 1950s. In 1961 he came to Nepal with his wife Manu where, a decade later, he was appointed Chancellor of the Royal Academy. This essay is excerpted from the biography, Against the Current: The Life of Lain Singh Bangdel—Writer, Painter and Art Historian of Nepal (Orchid Press, 2004). The book won Nepal’s prestigious ‘International Civil Golden Award 2004’.