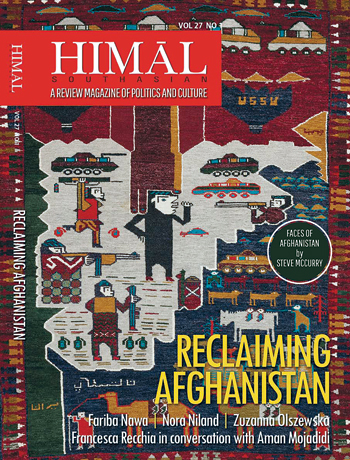

The latest issue of Himal Southasian explores the hopes and fears of the Afghans as the country prepares for the drawdown of the US and NATO troops that will be taking place by the year’s end.

In one of the articles comprising the package Reclaiming Afghanistan, the theme the latest issue of Himal Southasian explores, author Zuzanna Olszewska ends her story (Online identities; unfolding realities) with a poem by a young Aghan poet, Fatimah. In that untitled piece, the poet writes: That rainy day / children who had died / gathered around my baby / and I was afraid.

In expressing her fears for the future of her prematurely born baby girl, Fatimah, in fact, describes the reality of present-day Afghanistan, the uncertain future that rests after the drawdown of the US and NATO troops by the end of the year.

In expressing her fears for the future of her prematurely born baby girl, Fatimah, in fact, describes the reality of present-day Afghanistan, the uncertain future that rests after the drawdown of the US and NATO troops by the end of the year.

Will the ghosts of the past haunt the present and shape the future? Will those who can afford to leave the country depart in droves, leaving the rest unable to flee fight among themselves or against the Taliban? What are the chances of the Taliban forces wresting control from a weak democracy currently in place? They are all humans and poets just like Fatimah, worrying about the future of their land, as depicted by the Taliban poems writer Thomas Ruttig analyses in his story, Reed flute and gunpowder. What will happen to the voices of the liberals that have flourished in the last decade? Will refugees like Zarmina (Winter, spring, summer, autumn) and the Afghan diaspora end the cycle of generational exile and return home to build the country? What will happen to the thriving Afghan cricket and its self-made cricketers? Now with the waning international interest in the land that saw decades of war, what roles can the rest of the South Asian states play?

The latest Himal quarterly does not have definitive answers to these questions, but the writers of the seven stories in the thematic package and five from Himal’s archivetry, in their portrayals of a humane Afghanistan, pondering on the Afghans’ hopes, fears, aspirations and struggles.

One way to address these emotions, writes Shanthie D’souza in her piece, Back to Southasia, is by allowing Afghanistan to be the “land bridge” between South and Central Asia, as it once was. This, the writer says, will open economic opportunities for Afghans and the rest of the inhabitants of South Asia. Can the rest of us import more than just nuts and carpets from the eighth member of SAARC? Can we increase our intra-regional trade from a mere 4 percent and help Afghanistan find its political stability? As D’souza writes, even though SAARC is a lumpen organisation, this is doable, if only India and Pakistan would forego their sniping.

One of the best things about the bookazine (book + magazine) Himal is that readers can read at their own pace, flitting pages and pages, one story after another, looking for answers to tough questions on Afghanistan, until the next issue comes out in three months. This is not to say that Afghanistan should be forgotten after the arrival of the next thematic package. On the contrary, the book style allows the magazine to stay in shelves waiting for readers to find answers in between the lines. What do the seventeen pairs of piercing eyes that Steve Mcurry captures in his graphic feature see and love? How can we, Afghans or not, help them get what they long for?

If readers cannot find solutions in stories focused on Aghanistan, perhaps they can find one in the captivating story on Bangladeshis trapped in enclaves in India, or in the review of stories on the India-Pakistan Partition.