The Rato Machhindranath festival represents a microcosm of how Nepali society functions at large. Its story is particularly poignant in the post-earthquake milieu.

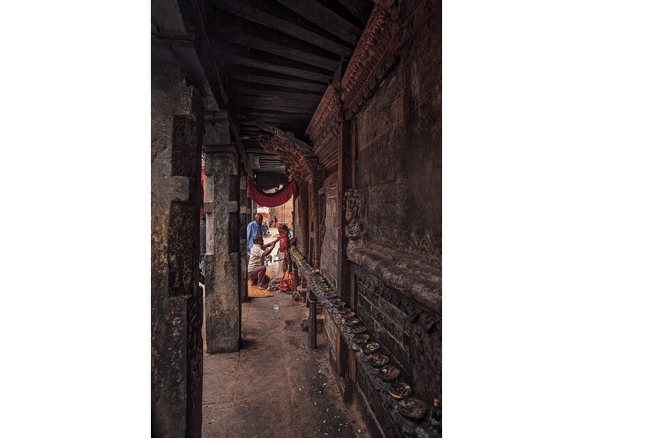

Days before the earthquake, Kathmandu Valley was eagerly waiting for the 12-year Bunga Dyo Jatra. The 32-foot towering chariot of Bunga Dyo (Rato Machhindranath) was due to complete a route back to Bungamati, from where it had begun, after a visit Patan and Jawalakhel.

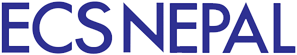

When the Jatra was in full swing, people stood on their toes to get a better view of the celebration, as the clashing of cymbals reverberated all around. The gurju paltan played age-old tunes, while devotees cast rice grains into the air to worship Bunga Dyo, the god residing in the chariot.

But, sadly, the Jatra was put on hold after the earthquake. The towering mast, and a Bhairav wheel (the wheels of the chariot are symbolic of the protective deity Bhairav), were damaged during the earthquake. The chariot, which was stationed in Chhyasikot, was rebuilt to restart the Jatra again.

But, historically, there have been a good number of obstacles due to accidents and disasters during the festival. This wasn’t the first disaster, and perhaps that is why this earthquake does not discourage Nepalis from celebrating festivals. Instead, for them, it is a way of celebrating life. For them, life continues even in the midst of disasters.

It is said that, if the chariot falters or collapses, or is damaged during the festival, it would pose a threat to the royal family (now those in power), and sometimes to the entire community. There have been instances in history that have proven the belief to be true. In A.D. 1680, when the paint on the clay statue of Rato Machhindranath wore off, Nripendra Malla, the king at the time, passed away. It has also been chronicled that when the paint on the statue faded again during the festival in A.D. 1817, an earthquake struck the country. Rational thinking is often overtaken by myths during this Jatra. An interesting, but tragic, story is that of King Visvajit Malla. He thought he had seen the deity turn its back on him when he had attended the festival. That same day, he was murdered.

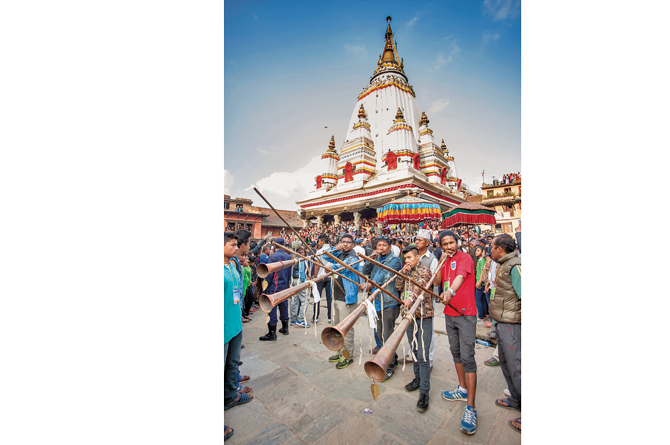

Kapil Bajracharya, one of the eldest gurjus (priests) in Bungamati, tells me that, if a house or a wall blocks the way of the chariot, the house is bulldozed instead of finding another way. “Is it right to knock down the house just because it stands on the way? Isn’t that unfair?” I had asked. His answer was: “The festival is very important, the deity represents compassion; it was through this deity that the endless drought caused by Gorakhnath (the revered sage of Gorkha) was lifted.”

Deepak Gurju, a priest in Patan, tells me another story of how Junga Bahadur Rana (who began the 100-year Rana regime) became the prime minister of Nepal. The story surprises me, because it’s different from what I have read in books. I had read that it was after the Kot Parva (a massacre in Hanuman Dhoka) that the Rana regime started. However, in this story, Junga Bahadur Rana was attending the Rato Machhindranath festival, during which, the flag on the top fell on his head. It was then believed that the deity had blessed him, and given him the opportunity to rule over Nepal.

As far as festivals are concerned, myths and beliefs outweigh logical reasoning. These stories, however, live in our communities and teach us about life. It wouldn’t be wrong to believe in these stories if you want to; the festival itself teaches that there is no other truth than hard work. Years and years ago, a drought in Kathmandu Valley had everyone in despair. It was King Narendra Dev, tantric priest Bandu Dutta Acharya, and a farmer from Lalitpur, who together with the Karkotak Nagraj (king of serpents) worked hard to bring the red deity to Kathmandu from Kamrupa Kamakchya in India, after plotting to deceive the deity’s demon father (a yaksha). The arrival of the red deity, Rato Machhindranath, into the valley ended the drought, and bestowed rain once again.

“The festival symbolizes hope for the people. It honors the compassion of Machhindranath, who agreed to stay away from his family to protect the valley from famine,” says Deepak Gurju.

And, that is perhaps why people made it a point to celebrate the 12-year Bunga Dyo Jatra even after the earthquake. This year, in October, the chariot made its arduous journey back to Bungamati, months after the April 25 earthquake. The losses have not affected the people’s faith, for the Jatra brings along hope, teaches us lessons for living, and reminds us of the efforts we need to make to celebrate life.